|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

This issue’s interview is a double-thrill. First, I spoke to Kent Alexander. He was the U.S. Attorney in Atlanta involved in the Richard Jewell-Olympic bombing case. Kent wrote the letter that cleared Jewell and co-wrote the book on which the recent Clint Eastwood-directed movie “Richard Jewell” was based. Kent’s book, “The Suspect,” was “couldn’t put it down.” There is a reason why it has a 5-star rating on Amazon with 150 reviews. That is really hard to do.

Thrill part 2 – The interview with Kent was originally published on the ABA Journal’s website. It was really exciting to publish a piece with such a venerable publication of the profession.

The interview with Kent is here: https://www.coverageopinions.info/KentAlexander.pdf

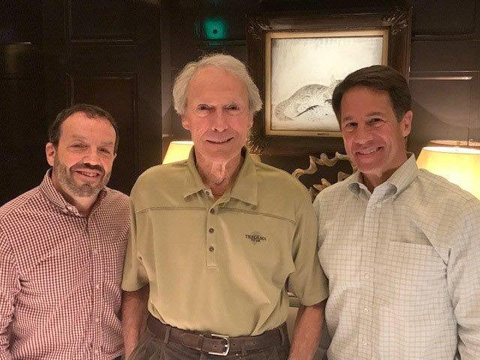

Kent Alexander and his co-author, Kevin Salwen, were also consultants on the “Richard Jewell” movie. |

| |

|

| |

Kevin Salwen, Clint Eastwood and Kent Alexander |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

First It’s Candy – Then It’s Gum: Is There Coverage For A Case Of Razzles Falling On Your Head?

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

When policyholders are denied a defense, because the standard is “four corners,” it can be a frustrating outcome for them. Consider this. The allegations in the complaint dictate that there is no potential for coverage. So there is no duty to defend. But the policyholder can point to other information, so-called “extrinsic evidence,” that, if considered, would trigger a duty to defend. The policyholder can see the duty to defend. It is in its grasp. But, alas, it can’t reach it because the court is constrained by the four corners of the complaint.

This frustration was on display in The Candy Cavity v. Lollipop Risk Retention Group, No. 20-1579 (Wis. Cir. Ct., Milwaukee Cty., Jan. 7, 2020). The Candy Cavity is a nook of a candy store located in the lobby of an office building in downtown Milwaukee. The store is quite small and storage is at a premium. Boxes of candy are piled haphazardly and precariously all throughout the store.

This proved to be detrimental for Lars Johansson, an architect who worked in the office building where The Candy Cavity was located. Johansson stopped into the store one day, as he often did, to pick up some Swedish fish. As a native of Stockholm, Johansson was often homesick and found that eating a quarter pound of Swedish fish was a pick-me-up.

Unfortunately for Johansson, while he was filling a bag with his favorite candy, a case of Razzles fell upon his head. It had been at the top of twelve stacked and wobbly boxes. Johansson was knocked to the ground. He suffered a concussion and a fractured bone in his neck. The injuries were serious, but could have been far worse.

Johansson filed suit against The Candy Cavity. The candy store sought coverage from its liability insurer, Lollipop Risk Retention Group. However, Lollipop RRG disclaimed coverage for a defense, citing the policy’s “gum exclusion,” which provided: “This insurance does not provide coverage for bodily injury caused by, arising out of or resulting from gum.”

All of Lollipop’s policies contained a “gum exclusion,” as the Risk Retention Group had been saddled with claims for damage to dental work caused by gum chewing. The complaint alleged that injury was caused by “Johansson being struck by a case of Razzles gum.” Lollipop RRG disclaimed coverage for a defense, stating that the claim fell squarely within the “gum exclusion.”

The Candy Cavity undertook its own defense. But, faced with being put out of business by the suit, the store, after chewing over its options, settled the claim with Johansson for $150,000. The settlement included an assignment of its rights under the Lollipop policy and a covenant not to execute.

Johansson filed suit against Lollipop RRG, alleging that the insurer improperly disclaimed coverage and did so in bad faith. Lollipop filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, stating that the “gum exclusion” barred coverage. Johannson responded that the “gum exclusion” was not applicable, at least for a defense, because Razzles are not simply gum. Rather, as the Razzles package clearly proclaims: “First its candy. Then its gum.”

Thus, Johansson argued that a defense was owed, as there was a possibility that Razzles are candy, and, thus, outside the scope of the “gum exclusion.” Johansson acknowledged that, for purposes of indemnity, it would be up to a trier of fact to determine if Razzles are candy or gum. That would determine if the “gum exclusion” applied.

The court granted Lollipop’s motion for judgment on the pleadings, explaining its decision as follows: “Of course Razzles are first candy and then gum. Everyone, including this court, knows that. But, for purposes of determining if Lollipop had a duty to defend the Candy Cavity, for the Johannson suit, the court is not permitted to consider Razzles’s dual identity as set out on its package. Rather, based on this state’s strict “four corners” test, for determining if a defense is owed, as set out in Water Well Solutions Serv. Group Inc. v. Consol. Ins. Co., 881 N.W.2d 285 (Wis. 2016), the court is only permitted to consider the allegations in the complaint. The pleading unambiguously alleged that Razzles are gum. Therefore, Lollipop’s determination, that it had no duty to defend the Candy Cavity, was correct. A sticky situation indeed. But the duty to defend is based on what the complaint says -- and not what the court knows.” The Candy Cavity v. Lollipop Risk Retention Group at 7.

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Encore: Randy Spencer’s Open Mic

Insurance Company Spokespeople That Actually Make Sense

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Next week [change to month here] the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament will be in full swing. Besides the players on the court and fans in the stands, your television will also show lots of team mascots and their shenanigans. There will be giant heads of every size, shape and stripe. You’ll see Clemson’s adorable tiger, who looks like Tony the Tiger’s brother. The Michigan State Spartan will be there, as long as he’s not in court fighting a copyright suit by USC’s Trojan. Duke’s masked Blue Devil, who is disliked as much as Duke, will also be in attendance.

While mascots are usually associated with sports, there are plenty in the insurance world too. They are probably better called spokespeople, but their purpose is similar. You know who they are. Their companies have spent billions of dollars over the years to make sure of it. I enjoy the characters that some insurance companies have developed over the past few years to promote their brands. I love the Gecko -- and follow him on Twitter. Allstate’s Mayhem Man keeps my interest. I’m a big fan of the Farmer’s Guy and have thought about getting that tweed jacket and vest combination. And as long as we’re on the subject…. Progressive’s Flo is getting a little long in the tooth. It’s time for her pension to vest.

But what I find curious about these insurance spokespeople is that they have no connection to insurance. What does a talking lizard have to do with auto insurance? Snoopy is the Fonz of dogs, but I don’t think about life insurance when I see him on the Met Life blimp.

Wouldn’t it make more sense for insurers to use characters whose appearance actually have a connection to the insurance policy that they are trying to sell. Consider these insurance spokespeople that insurers should be using:

Take an insurer trying to sell high level excess policies. If I saw the Jolly Green Giant I would definitely think to myself – You know, maybe I should buy coverage excess of $50 million.

And who better to sell the $1 million primary policy in that new $100 million tower? The Oomph Loompahs of course.

And what about a spokesperson for car insurance that actually has something to do with cars? Kitt from Knight Rider can talk and he probably isn’t too busy these days. Give him something more to do than just sitting around Hoff’s driveway.

Fire insurance policies? “Hi there, this is Smokey the Bear for Fire Mutual. You shouldn’t play with matches, but, if you do….

If McGruff the Crime Dog told me to buy a fidelity policy I couldn’t sign up fast enough.

Bob the Builder was born to hawk builder’s risk policies.

If a company can’t sell life insurance with the grim reaper as its spokesman then it should get out of the business.

Traveler’s Insurance – Waldo (of Where’s Waldo fame) should be all over that!

Flood Insurance – So easy. Noah

Pet insurance? Scooby Doo is perfect with all that hijinks he and Shaggy get into. And you could get him for practically nothing. He would take payment in Scooby Snacks.

If Goofy can’t sell professional liability policies, who can?

If you are trying to sell pollution liability policies there could be no better spokesperson than a guy who has spent his entire life in a trash can. Get me Oscar the Grouch on the line.

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Breaking (Decided Friday): E-Mail Phishing Scam: Coverage For "Social Engineering"

No Coverage For “Computer Transfer Fraud:” Court Bucks Trend; Reopens Circuit Courts’ Split

Josh Mooney, White And Williams Cyber And Data Protection Group Chair Breaks It Down

|

|

|

| |

By Joshua A. Mooney |

With perhaps the exception of ransomware, the largest source of cyber loss for insurance carriers is phishing scams, commonly known as business-email-compromises (BECs), whereby an insured is tricked into sending money by wire transfer to a bank account controlled by a criminal organization. Some losses are seven-figures; some represent death by a thousand wounds. During the last two years, many courts have found for the existence of Computer Fraud coverage for such loss in somewhat complex and sometimes head scratching decisions.

Friday’s decision in Mississippi Silicon Holdings v. Axis Ins. Co., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 29967 (N.D. Miss. Feb. 21, 2020) marks some significant departures from current trends. While coverage was owed under a policy’s Social Engineering coverage part, the Mississippi federal court held that a loss from mis-wiring $1 million to a fraudulent bank account did not implicate Computer Transfer Fraud or Funds Transfer Fraud coverage. The court’s decision departs from more recent decisions involving the meaning of “direct” causation, and broadens the dispositive effect of language in the insurance provisions relating to the insured’s knowledge and consent of the wire transfers. The decision also breathes new life into the split among U.S. Courts of Appeals on the scope of insurance coverage in connection with BECs.

The insured Mississippi Silicon Holdings (MSH) manufactured silicon metal using as a part of its manufacturing process carbon electrodes. MSH purchased its electrodes from a Russian supplier, Energoprom. Miss. Silicon, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 29967 at *1. In October 2017, MSH’s Vice President of Finance and Chief Financial Officer (the CFO) engaged in email communications with Olga Rozina, an Energoprom employee, regarding purchases and invoices that had come due. On October 23, the CFO received an email listing “Olga Rozina” in the “from” line enclosing an attachment lisitng new bank information to which payments were to be wired. The email further stated that “MSH should send its payments to the new bank account, which was Energoprom’s agent collector's account, ‘due to issues [Energoprom was] having with [its] account.’” Id. at *1-2.

Pursuant to the request, MSH wired $250,000 to that account. The process involved a three-person verification. The CFO electronically logged into MSH’s transfer account with its bank and initiated the wire transfer. Id. at *2. Thereafter, a second MSH employee logged into MSH’s account and confirmed the transfer. Following this authorization, a bank representative telephoned a third employee, MSH’s Plant Manager, who verbally authorized the transfer. Id. at *2-3. Almost one month later, the imposter Rozina contacted the CFO again inquiring about the payment of two additional invoices in the amount of $775,851. The CFO initiated another wire transfer involving the same three-person verification process. Id. at *4. The fraud was discovered when Energoprom inquired about receiving payment for the outstanding invoices. Id.

MSH sought coverage under its Privatus Platinum Insurance Policy, which provides coverage for Social Engineering Fraud ($100,000 policy limit), Computer Transfer Fraud ($1 million policy limit), and Funds Transfer Fraud ($1 million policy limit). Id. at *4-5.

The Social Engineering Fraud insuring agreement covered:

The Insurer will pay for loss of Money or Securities resulting directly from the transfer, payment, or delivery of Money or

Securities from the Premises or a Transfer Account to a person, place, or account beyond the Insured Entity's control by:

a. an Employee acting in good faith reliance upon a telephone, written, or electronic instruction that purported tobe a Transfer Instruction but, in fact, was not issued by a Client, Employee or Vendor; or

b. a Financial Institution as instructed by an Employee acting in good faith reliance upon a telephone, written, or electronic instruction that purported to be a Transfer Instruction but, in fact, was not issued by a Client, Employee or Vendor.

The insurer concluded that coverage existed under the Social Engineering provision, but denied coverage for the Computer Transfer Fraud and Fund Transfer Fraud coverages, which each had significantly higher limits. Id. MSH disagreed, and coverage litigation ensued.

The policy’s Computer Transfer Fraud insuring agreement, similar to Computer Fraud insuring agreements in many policies, provided coverage for:

The Insurer will pay for loss of or loss from damage to Covered Property resulting directly from Computer Transfer Fraud that causes the transfer, payment, or delivery of Covered Property from the Premises or Transfer Account to a person, place, or account beyond the Insured Entity’s control, without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent. (emphasis added).

The policy defined Computer Transfer Fraud as “the fraudulent entry of Information into or the fraudulent alteration of any Information within a Computer System.” Id. at *13.

The insurer argued that the underlying claim did not satisfy insuring agreement’s causation requirement – “resulting directly from” – maintaining that “nothing ‘entered’ into or ‘altered’ within [MSH’s] Computer System (here the [MSH] email system) directly caused the transfer of any Money”; instead, the CFO working in conjunction with two other employees had caused the transfer of the Money. Id. at *13-14. Thus, because the fraudulent email itself had not manipulated MSH’s computer system, but instead only requested MSH’s employees to undertake an affirmative action, a “Computer Transfer Fraud” did not directly cause the transfers. Id. at *14. In other words, the employees’ affirmation actions were intervening events that broke the causal connection between the fraudulent email and the loss, rendering the Computer Transfer Fraud coverage inapplicable. MSH, on the other hand, argued that the fraudulent email, which ultimately caused the CFO to act and commenced the chain of events, was sufficient to trigger coverage. Id.

The court disagreed with MSH and determined that there was no direct causation to satisfy the insuring agreement for Computer Transfer Fraud coverage. Looking to the plain and ordinary meaning of “direct,” as defined by dictionaries including Black’s Law Dictionary, the court held that the word required an “immediate” causation, a standard more stringent than proximate causation. The court explained: “The Court finds it undeniable that the [original] October 23 email set in motion a series of events which ultimately led to the loss. It is also clear that the emails from [the imposter] ‘Olga Rozina’ did not themselves manipulate MSH’s system and automatically transfer the funds. Rather, the emails requested that MSH engage in affirmative conduct, particularly, initiating a transfer to the [imposter’s bank] account listed on the attachment.”

Critically, the court acknowledged MSH’s contention that the fraudulent email may have proximately caused the loss, but concluded that in any event the policy’s language would not allow coverage under such a determination: “While the Court recognizes and appreciates MSH's argument in favor of a ‘proximate cause’ standard, it cannot be ignored that the provision itself specifically requires that the fraudulent act directly cause the loss. And it further cannot be ignored that MSH's employees, not the fraudulent emails themselves, actually initiated the transfer. If a proximate cause standard or some other more expansive coverage was intended, that language undoubtedly could have been included in the Policy. However, it was not. Id. at *15-16 (emphasis in original).

Because the fraudulent email had not manipulated MSH’s computer system to ‘automatically transfer the funds,’ the events did not implicate coverage under the insuring agreement.

However, the court went on further to explain that even if direct causation did exist, coverage still would not exist because of the “without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent” clause in the insuring agreement. The insurer contended that the requirement was not satisfied because three separate MSH employees had knowledge of, and explicitly authorized, the wire transfers, thereby precluding coverage. The insurer argued that: “… the inclusion of the ‘without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent’ language, clearly establishes that there is no coverage ‘where an insured knowingly wires money to another (later determined to be [a] fraudster). Rather, in order for a loss to be covered under this insuring agreement, the fraudster must cause the transfer of currency, through a hack, and without the insured being aware.” Id. at *17.

The court agreed, concluding that the employees’ knowledge and authorization of the wire transfers on the insured’s behalf precluded coverage: “In the Court’s view, the inclusion of the ‘knowledge or consent’ requirement is telling as to the coverage that was intended. Had the provision been intended to cover losses which were specifically authorized by MSH’s employees acting in reliance upon false or fraudulent information, the ‘without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent’ language could have been omitted altogether. The inescapable fact, however, is that the ‘without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent’ language is included in the provision, and coverage therefore clearly and unambiguously only applies for losses that occur without MSH's knowledge or consent.” Id. at *19. In other words, the ‘knowledge or consent’ clause precluded coverage for mis-wiring funds by artifice or trickery.

The court also looked to the coverage under the social engineering agreement to further bolster its conclusion that the ‘knowledge or consent’ clause precluded coverage for loss by trickery. Noting that coverage under the Social Engineering Fraud provision did not preclude coverage elsewhere under the policy, it also noted that the provision provided guidance when interpreting the Computer Transfer Fraud provision. Id. at *19-20. “Had the Computer Transfer Fraud provision been intended to cover a loss occurring when a funds transfer was effectuated by an employee acting in good faith reliance upon an electronic instruction which was ultimately determined to be fraudulent (exactly what occurred in this case), the same language used in the Social Engineering Fraud provision could have been incorporated into the Computer Transfer Fraud provision.” Id. at *20.

Because it was not, the court would not read trickery into an exception to the coverage provision’s restriction: “Ultimately, at least three MSH employees had knowledge of, and specifically authorized, the transfers. MSH cannot escape that reality, and its attempts to invoke coverage despite its employees’ undisputed knowledge and explicit authorization of the transfers bends the language of the Computer Transfer Fraud provision beyond the breaking point.” Id. at *21.

Finally, the court determined that the underlying phishing scam did not implicate the Fund Transfer Fraud. The provision covered: “The insurer will pay for loss of Money or Securities resulting directly from the transfer of Money or Securities from a Transfer Account to a person, place, or account beyond the Insured Entity’s control, by a Financial Institution that relied upon a written, electronic, telegraphic, cable, or teletype instruction that purported to be a Transfer Instruction but, in fact, was issued without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent.” Id. at *21-22 (emphasis added).

Again, the court held that the without “knowledge or consent” requirement was not met. “However, the impediment to coverage is that the transfer instruction upon which Trustmark Bank relied in order to complete the transfer was not ‘actually . . . issued without the Insured Entity’s knowledge or consent.’ … The undisputed evidence establishes that all three [MSH] employees, acting independently of each other, authorized Trustmark Bank to complete the transfers.” Id. at *23.

Also rejecting the contention that the court’s reading of the without ‘knowledge or consent’ requirement rendered the Computer Transfer Fraud and Fund Transfer Fraud coverages superfluous, the court explained: “While the coverage afforded under the Funds Transfer Fraud provision is similar, that provision requires that the loss involve a financial institution's reliance on an instruction by the insured which was actually issued without the insured’s knowledge or consent. The Computer Transfer Fraud provision would apply when the insured's system is manipulated without the insured's knowledge and effectuates a transfer, while the Funds Transfer Fraud provision is only applicable when the financial institution relies upon an instruction from the insured which was ultimately not provided by the insured.” Id. at *24-25.

What this case means:

There is a lot to digest here, not the least of which is the court’s discussion of the Computer Transfer Fraud’s direct causation requirement. The recent trend among court decisions has been to hold the direct causation requirement satisfied where a fraudulent email triggered a chain of unbroken events that resulted in the wire transfer of funds to an account controlled by cyber criminals. E.g., American Tooling Ctr., Inc. v. Travelers Cas. & Sur. Co. of Am., 895 F.3d 455, 461-62 (6th Cir. 2018) (“here the impersonator sent ATC fraudulent emails using a computer and these emails fraudulently caused ATC to transfer the money to the impersonator”).

The Mississippi Silicon court looked beyond the use of emails, citing with approval the reason expressed in Apache Corp. v. Great Amer. Ins. Co., 662 Fed. App’x 252, 258 (5th Cir. 2016). There, the court held the use of emails were incidental to the loss resulting from a BEC, concluding that “[t]o interpret the computer-fraud provision as reaching any fraudulent scheme in which an email communication was part of the process would . . . convert the computer-fraud provision to one for general fraud.” Id. Recent decisions in the Second and Sixth Circuits appeared to eschew such reasoning; Mississippi Silicon it back to the forefront.

Even the Second Circuit’s interpretation of the effect of PHP scripting in Medidata Sols, Inc. v. Fed. Ins. Co., 729 Fed. App’x 117, 119 (2d Cir. 2018) is contradicted here. Medidata held (I believe mistakenly) that the integrity of insured’s email system had been compromised by the use of a PHP script in the fraudulent email. Here, Mississippi Silicon requires more, holding that short of showing that the email both “manipulate[d] MSH’s system and automatically transfer[red] the funds,” the insuring agreement’s causal requirements were not satisfied. Given the amount of money at issue, it may be likely that the Fifth Circuit reviews this case on appeal.

From a cybersecurity standpoint, this case offers another observation. The insured had initiated a process whereby three separate employees had to approve a wire transfer that exceeded $100,000 in value. Nowhere in that process did there appear any requirement that, upon the change of banking information, the vendor itself be contacted using pre-existing contact information. A single phone call to Energoprom would have revealed the fraud and prevented the insured from wiring $1 million to a fraudulent account.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

If Jane Austen Worked In Insurance Coverage

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

January 8th was Elvis’s 85th birthday! The King has long left the building. Well, not all buildings. He is still in the courthouse. I hope you’ll check out my Wall Street Journal article on Elvis’s place in the judicial system and court opinions:

https://www.coverageopinions.info/ElvisAaronPresley.pdf

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Can’t Get Tickets For The Super Bowl? Sue The NFL

|

|

|

| |

A few days before Super Bowl LIV – where the San Francisco 49ers totally choked; and Patrick Mahomes was a total phenom – The San Francisco Chronicle published my article about lawsuits brought by fans over their inability to get access to tickets to the big game. Of course such lawsuits have been filed. The Super Bowl is the granddaddy of the tough ticket. And litigation is a favorite solution to problems. Viola. I hope you’ll check out the article here: https://www.coverageopinions.info/SuperBowlTickets.pdf

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Contest Results Are In: Please Help To Solve An Argument Between My Wife And Me

|

|

|

| |

In the last issue of Coverage Opinions I asked readers to please help me solve an argument with my wife over the legality of a parking spot.

In general, a sign in a municipal lot near my house stated that it was open for public parking after 4 PM. Another sign, just feet away, stated that a certain spot was reserved for the fire chief. So the debate between my wife and me was whether the fire chief’s spot was available for public parking after 4 PM. Or was the fire chief’s spot an exception to the 4 PM rule.

I said no way you can park in the fire chief’s spot after 4 PM. My wife concluded that you absolutely can.

So in the last issue I included pictures of the two signs and asked CO readers to vote for who is right. The full article is here: https://www.coverageopinions.info/Vol9Issue1/Contest.html

Dozens of responses came in. There were two overwhelming consensuses: (1) You definitely cannot park in the fire chief's spot after 4 PM; and (2) Happy Wife = Happy Life. Therefore, yes, you definitely can park in the fire chief's spot after 4 PM.

I also stated that the funniest response would get a copy of Insurance Key Issues. The winner is Carrie Van Hoff, AVP and Senior Coverage Counsel with Zurich in Schaumburg, Illinois with this response:

“As we all know, the language of the endorsement changes the policy and controls. The parking lot sign is the policy – the fire chief spot is the site specific endorsement. The fire chief’s spot is reserved all the time. Don’t park in that spot. (Of course, if you have further information that might affect our analysis, please feel free to direct it to the undersigned.)”

There were lots of funny responses, but the last line clinched it for Carrie.

BTW, my wife scoffed at the vote results.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

“Alienation of Affections” Part II – Is It Insurable?

|

|

|

| |

On Valentine’s Day, The Wall Street Journal published my article on Alienation of Affections claims. In plain English – in six states there exists the right to bring a suit against the person who had an affair with your spouse that caused the break-up of your marriage. I know. It’s hard to believe.

The piece looked at some of these cases and the legal issues that arise (unusual ones, as you can imagine). I hope you’ll check it out:

https://www.coverageopinions.info/WallStreetLostLove.pdf

Part II – Is It Insurable?

We all know the usual follow-up question after a tort verdict: Is it insurable? There is not much law addressing whether a judgment, for Alienation of Affections, is insurable under a liability policy. However, not too long ago – 2007 -- the South Dakota Supreme Court addressed this very issue in State Farm v. Harbert.

The court’s decision is very straightforward and unambiguous.

David and Peggy Kalt were married on Valentine’s Day in 1976. In 2001, Peggy began engaging in an extra-marital affair with Thomas Harbert, an orthopedic surgeon in a practice where Peggy was employed as clinic manager.

David discovered the affair, filed for divorce against Peggy and an action against Harbert alleging alienation of affections.

Harbert sought coverage for the suit under a personal umbrella policy issued by State Farm. State Farm undertook Harbert’s defense under a reservation of rights and commenced an action seeking a declaratory judgment that it had no obligation to defend or indemnify Harbert for the suit. Of note, Harbert, after seeing challenges to obtaining coverage, amended his complaint to include a cause of action for invasion of privacy, since the policy specifically provided coverage for it.

The trial court concluded that no coverage was owed. The South Dakota Supreme Court affirmed.

First, the Supreme Court needed to figure out what to do with the claim for invasion of privacy. The court decided that, despite its name, it was still a claim for alienation of affections: “By amending his complaint to include invasion of privacy, Kalt was, in essence, attempting to repackage his alienation of affections claim as an invasion of privacy claim to create insurance coverage for Harbert in the underlying action. The privacy claim stemmed from the same underlying injury as the claim for alienation of affections: allegedly the intentionally harmful, voluntary adulterous conduct leading to the dissolution of Kalt’s marriage. Thus, it cannot be said that the privacy claim is separate or distinct from the alienation of affections claim.”

With that issue put to bed, the court concluded that coverage for the claim for alienation of affections was precluded by the intentional torts exclusion: “At the heart of an alienation of affections tort is the specific intent to alienate the affections of one spouse away from the other spouse. Therefore, the resulting injury is always ‘expected or intended.’ As a result, State Farm has no duty to defend Kalt’s alienation of affections claim because it falls within the intentional tort exclusion as an expected or intended loss and is, therefore, not covered by Harbert’s policy.”

Lastly, the court added a public policy belt to the expected or intended suspenders: “Pursuant to this State’s public policy, an individual is not allowed to impute financial responsibility to his insurance company for his own intentional torts. Such responsibility stays with the insured. Here, Harbert allegedly committed a wrong by enticing Peggy’s affections away from Kalt. Harbert is attempting to shift responsibility for these actions to his insurer, State Farm. The alienation of affections is conduct that should not be encouraged by the protection of financial impunity. To permit such ‘affair insurance’ would defeat the purpose of punishing and deterring individuals for their own tortious acts. In accordance, we hold that insuring the tort of alienation of affections is contrary to South Dakota public policy.”

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

At Least One Insurance New Year’s Resolution Kept! Imagine That!

|

|

|

| |

In the last issue of Coverage Opinions I set out my insurance new year’s resolution for 2020, including this one: I resolve to solve the mystery why many declarations pages state that the policy periods are from 12:01 Standard Time. Most of the country is on Daylight Saving Time for half the year.

Thanks to a long-time and wise CO reader -- Patrick McCoy, Managing Counsel for Travelers in St. Paul -- I can check at least one resolution off the list as having been kept! Patrick sent me the following very impressive explanation of the standard time issue:

Prior to the enactment of the Uniform Time Act of 1966, 15 U.S.C. § 260(a), some courts defined daylight saving time (sun time) and standard time separately and applied whichever the contract explicitly referred to, regardless of the actual time in use in the state at the time of the occurrence or expiration. See, e.g., Seligson v. Fireman’s Fund Indemn. Co., 196 N.E. 611 (N.Y. 1935); Goodman v. Caledonian Ins. Co. of Scotland, 118 N.E. 523 (N.Y. 1917).

Since the Uniform Time Act was enacted, courts have typically held that standard time refers to the time currently in use in the state because that statute “advance[s]” standard time during the daylight saving time period. Thus, the advanced time becomes standard time during the 7+ months of the year that daylight saving time is in effect. 15 U.S.C. § 260(a) (“[T]he standard time of each zone established by sections 261 to 264 of this title, as modified by section 265 of this title, shall be advanced one hour and such time as so advanced shall for the purposes of such sections 261 to 264, as so modified, be the standard time of such zone during such period.”). See also 49 C.F.R. § 71.2 (“The Uniform Time Act of 1966… requires that the standard time of each State observing Daylight Saving Time shall be advanced 1 hour beginning at 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday in April of each year and ending at 2:00 a.m. on the last Sunday in October. This advanced time shall be the standard time of such zone during such period.” (emphasis added)).

Two insurance-specific cases have held that “standard time” in an insurance policy refers to the current time in any given state. In Empire Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Continental Cas. Co., 426 F. Supp. 2d 329 (D. Md. 2006), the court concluded that “daylight saving time is the ‘standard time’ when daylight saving time is in effect.” Id. at 331. Likewise, in Miracle Auto Center v. Superior Court, 80 Cal. Rptr. 2d 587 (Cal. App. 1988), the court held that “standard time,” as used in a commercial general liability insurance policy to determine coverage expiration, meant the time currently in use in the state whether standard time or daylight saving time is in effect.

|

*** |

Me again. It was neat to see that at least two courts have addressed the “standard time “ issue. Needless to say, it takes very usual and rarely-occurring facts for the issue to arise. Cases in point:

If you like minutiae and technical arguments, you’ll love this one from Empire Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Continental Cas. Co.: “Empire acknowledges that the underlying accident occurred on May 7, 2004 at 12:28 a.m., but contends that its policy was not yet in effect. To be more precise, Empire claims that since daylight saving time was in effect in New Jersey on the date of the loss, the accident actually occurred on May 6, 2004 at 11:28 p.m. ‘standard time.’ Accordingly, it is CNA’s policy -- which did not expire until May 7, 2004 at 12:01 a.m. “standard time” -- that was in effect at the time of the loss.”

But, as noted above in Patrick’s discussion of Empire Fire & Marine, “daylight saving time is the ‘standard time’ when daylight saving time is in effect.” Thus, the court concluded that the accident took place at 12:28 a.m. “standard time.” Empire’s policy was in effect at the time of the accident and not CNA’s.

Then there’s this from Miracle Auto Center v. Superior Court: “Pacific denied petitioner’s fire claim loss because the policy had been canceled as of 12:01 a.m. on June 29, 48 minutes before the fire was discovered. Petitioner sued alleging bad faith and breach of contract and requesting declaratory judgment that the loss happened before the cancellation of the policy. Petitioner sought summary adjudication challenging Pacific’s affirmative defense that the policy cancellation was effective before the fire occurred. Petitioner contended the plain meaning of the policy term “standard time” meant standard Pacific time. Thus, because daylight saving time was in effect, the fire had actually been discovered one hour earlier at 11:49 p.m. on June 28, 1997.”

But, as noted above in Patrick’s discussion of Miracle Auto Center, the court concluded that “standard time,” as used in a CGL policy, means the time currently in use in the state, whether standard time or daylight saving time is in effect.

Thanks to Patrick McCoy for, uh, shedding light on the standard time issue. Now if he could just get me to the gym a little more frequently!

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Coverage Counsel Authors Insurer’s Letters -- Leads To Waiver of Attorney-Client Privilege

|

|

|

| |

The other thing more unexciting than a discovery dispute is reading about someone else’s discovery dispute.

But the Washington federal court’s decision in Canyon Estates Condo. Association v. Atain Specialty Ins. Co., No. 18-1761 (W.D. Wash. Jan. 22, 2020) is no snoozer.

The decision is brief but has a lot to say.

A condominium association was seeking unredacted copies of its insurer’s claims file documents and invoices for activities performed by its outside coverage counsel, Michael Hooks.

The insurer maintained that the documents were precluded from discovery on account of attorney-client privilege.

The court set out the rules concerning attorney-client privilege in the context of a coverage dispute. As a starting point, “there is a presumption of no attorney-client privilege relevant between the insured and the insurer in the claims adjusting process.”

However, the court noted that the presumption can be overcome “by showing its attorney was not engaged in the quasi-fiduciary tasks of investigating and evaluating or processing the claim, but instead in providing the insurer with counsel as to its own potential liability; for example, whether or not coverage exists under the law.”

So the question was this – Was Mr. Hooks, as outside coverage counsel, engaged in evaluating or processing the claim OR was he providing the insurer with counsel as to whether or not coverage exists under the law?

The insurer, seemingly prepared for this issue, maintained that it “consciously chose to keep [Michael] Hooks, its outside counsel, separate from the claim investigation, and he did not participate in the investigation or otherwise perform claim handling functions.”

But the court concluded that such declarations, about Mr. Hooks's role, were “pure amphigory.” [If you have to look that up, you are not alone.]

As the court saw it, Hooks “clearly—and arguably, knowingly—engaged in at least some quasi-fiduciary activities.”

A significant aspect of the court’s decision was that Mr. Hooks authored draft letters signed by the insurer and sent to the insured related to coverage and claims processing. As the court put it: “Assisting an adjustor in writing a denial letter is not a privileged task.”

What about if the outside counsel engages in what the court believes is claim investigation and also provides advice on whether or not coverage exists under the law. Here, “waiver of the attorney-client privilege is likely since ‘counsel’s legal analysis and recommendations to the insurer regarding liability generally or coverage in particular will very likely implicate the work performed and information obtained in his or her quasi-fiduciary capacity.” (citation omitted).

The court concluded that very few of the documents at issue are covered by attorney-client privilege. In addition, following an in camera review, the court noted that counsel has discoverable information related to the drafting of the letters that is relevant to the claims.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

It’s Back: Despite Keodalah, Washington Court Can’t Rule Out Bad Faith Claim Against Adjuster

White And Williams’s Tim Carroll Saw This Decision Coming

|

|

|

| |

My 2019 Top 10 Cases article included Keodalah v. Allstate Insurance Company, where the Washington Supreme Court held that an insurer-employee claims adjuster could not be sued for bad faith under Washington’s Consumer Protection Act.

The Keodalah article was written by my colleague, Tim Carroll. While Keodalah has been discussed, generally, as putting the kibosh on bad faith claims against an adjuster, Tim addressed the decision in more precise terms and concluded that the curtain may not have fallen. He stated:

“The dissenting opinion raises questions about whether an adjuster (or other insurance company agent) can be held liable for common law bad faith and certain other per se claims under the CPA. *** The lingering questions raised by the dissenting opinion in Keodalah beget another, more practical question. A trend emerged after the Washington Court of Appeals’ decision temporarily enabled a bad faith claim against adjusters. State court bad-faith suits began naming as defendants both the out-of-state insurance company and the Washington-domiciled adjuster, for the seeming purpose of destroying diversity of citizenship and blocking removal to federal court. Once removed, Washington federal courts ruled that the adjusters were properly joined as defendants because the claims against the adjusters were viable. Without diversity of citizenship, therefore, Washington federal courts relinquished jurisdiction and remanded the suits back to state court. The Keodalah decision suggests that trend should reverse itself. However, in light of the dissenting opinion, will Washington federal courts go back to remanding cases to state court, for lack of diversity, based on common law bad faith claims against a Washington-domiciled adjuster being viable?” (emphasis mine).

Well, this is exactly what happened in Leonard v. First American Property & Casualty Company, No. 19-06089 (W.D. Wash. Feb. 11, 2020).

Brandon and Alicia Leonard sued First American Property & Casualty, in Washington state court, for allegedly unreasonably denying and delaying coverage of a homeowner’s fire claim. In addition to suing First American, the Leonards also sued First American’s claims adjuster, Crawford & Company, and its employee. The Leonards asserted claims of insurance bad faith, negligent claims handling, negligent misrepresentation, and violation of the Washington Consumer Protection Act against Crawford and its employee.

First American removed the case to federal court. As First American saw it, Crawford and its employee were fraudulently joined “because the Leonards could not assert claims against First American’s insurance adjusters under Keodalah v. Allstate Ins. Co.” Therefore, so the insurer’s argument went, “[t]his would mean complete diversity is satisfied and this Court has subject matter jurisdiction over the case.”

The Leonards had a different take. They moved to remand, arguing that Keodalah only bars per se Consumer Protection Act claims and statutory bad faith claims against insurance adjusters. In other words, in the Leonards’ view, Keodalah did not address whether a common law bad faith claim could be brought against an adjuster. Therefore, there was nothing to say that it couldn’t be maintained.

The court agreed, turning to Justice Yu’s dissenting opinion in Keodalah, where he stated that the court wrongly overlooked the common law bad faith claims. “In light of this,” the Leonard court stated, “the Court cannot say that the Leonards’ claims against Crawford and [its employee] have no possibility of success.”

The court also went a step further: “Even if this were not the case, the Court sees no reason why the Leonards should not be allowed to assert traditional CPA claims against Crawford and Johnson. Such a claim is not premised on the existence of a tort duty and therefore cannot be barred by Keodalah.”

To be clear, the Leonard court did not rule that an insured can recover for a common law bad faith claim against an adjuster. Rather, the court was addressing whether the adjuster had been fraudulently joined to defeat diversity. The test, for that question, was whether there was a “possibility” that the complaint stated a cause of action. And the court stated that it did. Therefore, as the adjuster was a property party, there was no diversity and the case was remanded to state court.

This is precisely the door that Tim Carroll said was left open by the Keodalah.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Court Decides If A “Stub” Period Gets A Separate Limit

|

|

|

| |

Boy I haven’t seen a case addressing a “stub” period for a while. This is the (unofficial) name used to describe a policy on the risk for at least a full year and then part of a subsequent year. Think of a policy on the risk for 15 months. The first 12 months are one policy period. The next 3 months are the “stub period.”

Why does this matter? The question sometimes arises whether the “stub” period is subject to its own limit of liability – the same as the prior 12 month period – or is simply tagged-on to the prior 12 month period. In other words, the prior 12 month period is now longer, but subject to the same limits.

This issue previously came up a fair amount in the context of claims for asbestos bodily injury and hazardous waste, under decades-old policies, that were often-times issued for three year periods. The policy would be cancelled early. Say, after 28 months. There are now 2 policy periods of 12 months each and a stub period of 4 months. Does the 4 month stub period gets its own full limit or is the prior 12 month period now 16 months and subject to the same limit?

The question was particularly acute in O’Reilly Auto Enterprises v. United States Fire Insurance Company, No. 17-3007 (W.D. Mo. Jan. 27, 2020) where the stub period was just 2 months.

The court in O’Reilly addressed a few asbestos bodily injury coverage issues. But I’ll discuss just the stub period here. Admittedly, O’Reilly is not your typical stub period case, as the policy at issue specifically addresses the issue more than in other cases. But it is still a worthwhile decision for anyone tackling a stub period.

The policy giving rise to the stub period dispute was issued by U.S. Fire from May 22, 1987 to May 22, 1990. However, it was cancelled effective July 22, 1988. Thus, it now had a 12 month period from May 22, 1987 to May 22, 1988 and a 2 month stub period from May 22, 1988 to July 22, 1988.

As you can imagine, U.S. Fire argued that the policy provides $2 million in limits. The insured saw it differently, arguing that the policy was subject to two sets of $2 million limits.

Of significance, the policy contained the following limits of liability provision: “The limits of the insurance apply separately to each consecutive annual period and to any remaining period of less than 12 months, starting with the beginning of the policy period shown in the Declarations, unless the policy period is extended after issuance for an additional period of less than 12 months. In that case, the additional period will be deemed part of the last preceding period for purposes of determining the Limits of Insurance.”

Also relevant, the endorsement that cancelled the policy – Endorsement 29 -- provided as follows: “IT IS AGREED THAT THE EFFECTIVE DATE OF CANCELLATION IS AMENDED TO JULY 22, 1988. IT IS FURTHER AGREED THAT THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS FOR THE POLICY PERIOD MAY 22, 1987 TO MAY 22, 1988 ARE EXTENDED TO JULY 22, 1988.”

Reading these provisions together, the court was left with two questions: “[D]oes Endorsement 29 result in a ‘remaining period of less than 12 months,’ which would provide a separate $2 million in coverage, or does it result in ‘an additional period of less than 12 months,’ which would provide no additional coverage?”

The court examined the circumstances, the little there was, surrounding the issuance of Endorsement 29. That didn’t resolve the ambiguity. So you don’t need me to tell you what the court’s decision was.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

Pollution Exclusion And Trout Spawning

|

|

|

| |

I follow pollution exclusion cases very closely. But despite how frequently they are handed down, I do not write about them too often in Coverage Opinions. Most are too similar to be all that interesting.

I need something a little unusual to have the mojo to write about a pollution exclusion case. The Fifth Circuit’s decision in Eastern Concrete Materials, Inc. v. Ace American Insurance Company, No. 18-11043 (5th Cir. Jan. 17, 2020) fits that bill. The decision started out fairly routine and it appeared that it was not going to make the cut. But an interesting finish changed that.

At issue is coverage for Eastern Concrete, a company that operates a rock quarry in New Jersey. It produces different sizes or gradations of stone. The smallest are called “rock fines.” For various reasons, substantial amounts of rock fines, contained in the company’s settling ponds, were released into Spruce Run Creek, causing “physical damage to the stream and stream bed by changing the flow and contours of the stream.”

This got the attention of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, which required Eastern Concrete to remove the rock fines and take preventative measures to stem downstream migration.

Eastern Concrete did so to the tune of $2 million. The company’s primary insurer, ACE, concluded that coverage was owed under its $1 million policy. Eastern then sought coverage from Great American Insurance Company, its umbrella insurer.

Great American filed an action seeking a declaration that it was not obligated to defend or indemnify Eastern Concrete. GAIC maintained that the pollution exclusion in its policy precluded it from owing any coverage. In pertinent part, the exclusion applied to liability “arising out of or in any way related to . . . discharge, dispersal, seepage, migration, release or escape of ‘pollutants.’” “Pollutants” is defined as “any solid, liquid . . . irritant or contaminant, including, but not limited to . . . waste material,” which “includes materials which are intended to be or have been recycled, reconditioned or reclaimed.”

A good chunk of the decision is devoted to a jurisdictional issue. It’s deadly dull and I did not read it. There is also a choice of law issue discussed. Also dull – as choice of law issues tend to be -- but I read it. The court held that Texas law applied, concluding that the state where the policy was issued controlled over the location of the insured risk.

The parties’ competing arguments came down to whether rock fines are “contaminates.” Eastern Concrete maintained that they are not: “[r]ock fines are simply ‘small particles of rock,’ and thus ‘are not dangerous’ and ‘do not . . . contaminate.’ To hold otherwise, Eastern Concrete cautions, would be to adopt the district court’s reasoning that rock fines became ‘contaminants when they were discharged and dispersed where they did not belong,’ a theory Eastern Concrete casts as dangerously overbroad because it allows anything (even water or bricks) to become contaminants if left in an inappropriate place.”

GAIC’s position was that Eastern was “inventing a ‘hazardousness’ requirement: ‘[N]othing in the ordinary sense of the word ‘contaminant’ or in the caselaw imposes such a restriction.”

The Fifth Circuit looked at two definitions of “contaminant” and concluded that neither fit when applied to whether the quality of the water in Spruce Run Creek was affected.

The court observed that, while the rock fines may have been undesirable, they did not make the creek impure or render it unfit for use. Indeed, according to the New Jersey authorities, the rock fines posed no threat to drinking water.

So it sounded like the court was headed for a decision that the pollution exclusion did not apply. But not so fast. The court concluded that, despite all that, the rock fines did in fact render the creek impure. Maybe not for humans – but trout: “[W]hen we look at the effects on the overall ecosystem, rock fines are contaminants. Eastern Concrete’s own counsel described the incident as pumping ‘a deleterious substance resulting in a negative impact to a trout producing stream and a documented habitat for threatened or endangered species.’ And Eastern Concrete’s expert explained that the incident ‘chang[e]d the flow and contours of the stream, including areas used for trout spawning’ and ‘physically cover[e]d the micro and macro invertebrates that serve as a food source for fish and other species.’ The rock fines, in short, ‘render[e]d [the creek] unfit for use’ as a habitat for trout and other species. This explains why Eastern Concrete was required to remove the rock fines from Spruce Run Creek.”

Eastern Creek is an interesting decision, looking at the “contaminants” question from the perspective of a less traditional impact. The rock fines posed no threat to drinking water, but the pollution exclusion still applied.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

A Rarity: An Interesting Case Involving Mobile Equipment [ISO Take Notice]

|

|

|

| |

Cases involving “mobile equipment” can be deadly dull. Given the complex definition of the term, they sometimes call for a tedious analysis. That was the situation in Penn-Star Inc. Co. v. Zenith Ins. Co., No. 18-1319 (E.D. Cal. Jan. 31, 2020). Yet, the decision still manages to be interesting. Given how critical the court was of the policy language – really critical -- the decision should give ISO something to think about. Granted, it’s just one decision. But the court was very troubled by the policy language at issue and it may have opened a door for others to challenge the “auto exclusion” on the basis that the “vehicle” in question was “mobile equipment.”

At issue was coverage for Golden Labor, a labor-services firm that provides farms with laborers. A farm laborer, obtained though Golden Labor, was driving a tractor when he was involved in an accident with an automobile. The driver of the automobile was killed and its three passengers were injured. Golden Labor tendered the subsequent suit to Penn-Star seeking coverage under a general liability policy. Penn-Star undertook the defense subject to a reservation of rights. Coverage litigation ensued.

At issue was the applicability of an amended “auto exclusion.” Specifically, before the court was the question whether the tractor was an “auto?” This got into the question whether the tractor was “mobile equipment,” as the definition of “auto” excluded “mobile equipment.” From there, the definition of “mobile equipment” includes “bulldozers, farm machinery, forklifts and other vehicles designed for use principally off public roads,” but specifically excludes “any land vehicles that are subject to a compulsory or financial responsibility law or other motor vehicle insurance law where it is licensed or principally garaged.”

Penn-Star’s argument was that the tractor is “mobile equipment,” since it is subject to a compulsory or financial responsibility law.

The court concluded that, for two principal reasons, the “auto exclusion” did not apply.

First, the court took issue with what it saw as the complexity of the policy: “[T]he provisions are not conspicuous. In order to reach the conclusion that the tractor at issue is not covered by the Penn-Star policy because it is a ‘mobile equipment’ subject to financial responsibility laws, the reader of the insurance policy must locate several provisions in a policy that is almost fifty pages long. Initially, the reader must find the auto exclusion, as amended by endorsement, which states that the insurance policy does not apply to bodily injury arising out of the use of any ‘auto.’ Next, the reader must find the definition of ‘auto,’ which explicitly excludes ‘mobile equipment.’ Thereafter, one would have to locate the definition of ‘mobile equipment,’ which explicitly notes that ‘farm machinery’ and ‘other vehicles designed principally for use off public roads’ qualify as ‘mobile equipment.’ At this point, the average insured might reasonably assume that a tractor constitutes farm machinery or an ‘other vehicle designed principally for use off public roads’ and is therefore not within the scope of the auto exclusion.”

But there was still another step, the court observed, as the definition of “mobile equipment” “goes on to exclude from its scope ‘any land vehicles that are subject to a compulsory or financial responsibility law or other motor vehicle insurance law where it is licensed or principally garaged.’ Here, this exclusion is not conspicuous since it is buried in the definitions section of the policy.”

The court also observed that “the auto exclusion, as amended by the endorsement, does not even alert the policyholder that its scope will or could be expanded by a definition that appears in a different section of the policy and not in the endorsement itself. . . . In short, the average lay reader would have a difficult time locating the limiting language and is not required to conduct such an arduous search for camouflaged exclusions. Accordingly, the court concludes that Penn-Star has not met its stringent obligation to alert a policyholder to limitations on anticipated coverage by hiding the disfavored language in an inconspicuous portion of the policy.”

Then, the court concluded that, even if the reader found all of these provisions, they would have difficulty figuring out if the tractor is subject to financial responsibility laws: “Although ‘Financial Responsibility Law’ may be an obvious reference to the Vehicle Code to lawyers and judges, . . . it is too vague to meet the stringent obligation of the insurer to limit coverage in plain and clear language. Here, in order for Golden Labor to understand the coverage provided to it, it was expected to either know the financial responsibility law . . . or know the discrete body of statutory law [] set forth within . . . the [California] Vehicle Code. The Penn-Star policy, however, does not reference the statutes embodying California’s financial responsibility laws, leaving the reader to determine what is meant by that language. Moreover, as demonstrated by Penn-Star’s own motion, even if a reader understood what was meant by that language, in order to reach the conclusion that the tractor at issue is subject to financial responsibility laws, one would need to: (1) locate the definition of ‘motor vehicle’ within California Vehicle Code § 415; (2) conclude that the tractor qualifies as a motor vehicle; and (3) determine whether the tractor, as a motor vehicle, was required to ‘establish financial responsibility’ pursuant to California Vehicle Code §§ 16020 and 16021. (See Doc. No. 32 at 20-21.) Assuming that a reader concluded that a tractor did not qualify as a ‘motor vehicle’ under § 415, one would apparently still need to determine whether the tractor qualifies as an ‘implement of husbandry’ as defined in §§ 36000 and 36015 or a ‘commercial vehicle’ as defined in § 260, both of which purportedly require the vehicle at issue to be registered or comply with financial responsibility law.”

Simply put, as far as the court was concerned, “Penn-Star presumed a level of sophistication and knowledge beyond that of an ordinary layperson and, therefore, the policy provision purporting to limit coverage d[o] not satisfy the requisite plain and clear criteria.”

Indeed, it was noted that Penn-Star’s own claims consultant, following its analysis, had concluded that a tractor is not a commercial vehicle that would be required to maintain proof of financial responsibility.

Not all states have California’s “conspicuous” requirement for purposes of the placement of language in a policy. However, the decision’s analysis, of whether a tractor is “mobile equipment,” could be used by policyholders anywhere to may hay with the complexity of the definition. This may be especially welcome when it comes to the financial responsibility law aspect of “mobile equipment” and its inter-relationship with the “auto exclusion.”

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 9 - Issue 2

February 26, 2020

No Coverage Under Primary. Wait, What About The Umbrella?

|

|

|

| |

Most of the time, when no coverage is owed for a claim under a primary liability policy, there is also no coverage owed under an umbrella policy. While the umbrella policy can provide broader coverage than the primary, the number of places where the coverage is broader is usually not many. But sometimes it is. And that was the lesson in Grange Mutual Cas. Co. v. Milano Enterprises, No. 1644 WDA 2018 (Pa. Sup. Ct. Feb. 10, 2020).

At issue in Milano Enterprises was coverage for Milano, for a fatal injury sustained by Carol Tait, when she was struck by a vehicle driven by Steven Krenke. Tait’s estate alleged that, at the time of the accident, Krenke was in the scope of his employment for Milano as a pizza delivery driver.

Grange Mutual asserted that it had no obligation to provide coverage to Milano, under a commercial general liability or commercial umbrella policy, as the injury was caused by an automobile accident. The trial court agreed that no coverage was owed under the commercial general liability policy but the same could not be said about the umbrella policy. The Pennsylvania Superior Court affirmed.

The decision is neither complicated nor surprising. The court described the allegations of the underlying complaint as follows: “Tait’s complaint alleges that while he was in the scope and course of his employment with Milano as a pizza delivery driver, Steven Vincent Krenke was operating ‘a vehicle’ on February 14, 2016, when he struck Carol Tait as she was attempting to cross Ohio River Boulevard in Bellevue, Pennsylvania, causing her to sustain fatal injuries. Tait’s complaint alleges that at the time of the accident, Krenke was driving with a suspended license and was driving under the influence of a controlled substance.

The complaint further alleges the following: [I]t is clear that [Milano] either did not conduct a simple review of Krenke’s criminal docket to discover the driving offenses or [Milano] did conduct a review, but allowed Krenke to drive for their business anyway despite his long history of criminal and driving offenses.

Furthermore, it is clear that [Milano] failed to have any policy or procedure in place to ensure that their delivery drivers had current and valid drivers’ licenses while working as delivery drivers for their business. At the time of this accident, Krenke did not possess a valid drivers’ license and should not have been operating a vehicle at any time and especially in the scope and course of his employment with [Milano].”

The decision, that no coverage was owed under the commercial general liability policy, but could be owed under the umbrella policy, came down to differences in the two policies’ “auto exclusions.”

The “auto exclusion,” in the commercial general liability policy, provides as follows:

This insurance does not apply to:

g. Aircraft, Auto or Watercraft

“Bodily injury” or “property damage” arising out of the ownership, maintenance, use or entrustment to others of any aircraft, “auto” or watercraft owned or operated by or rented or loaned to any insured. Use includes operation and “loading or unloading.”

This exclusion applies even if the claims allege negligence or other wrongdoing in the supervision, hiring, employment, training or monitoring of others by an insured, if the “occurrence” which caused the “bodily injury” or “property damage” involved the ownership, maintenance, use or entrustment to others of any aircraft, “auto” or watercraft that is owned or operated by or rented or loaned to any insured.

Now compare this “auto exclusion” to the “auto exclusion” contained in the umbrella policy:

This insurance does not apply to:

f. Auto Coverages

(1) “Bodily injury” or “property damage” arising out of the ownership, maintenance or use of any “auto” which is not a “covered auto[.]”

You can see where this is going. The “auto exclusion,” in the commercial general liability policy, states that it applies “even if the claims allege negligence or other wrongdoing in the supervision, hiring, employment, training or monitoring of others by an insured.”

However, the “auto exclusion,” in the umbrella policy, does not contain this expansive language.

Recall that the Tait complaint alleged that Milano “either did not conduct a simple review of Krenke’s criminal docket to discover the driving offenses or [Milano] did conduct a review, but allowed Krenke to drive for their business anyway despite his long history of criminal and driving offenses.”

Therefore, the “auto exclusion,” in the commercial general liability policy, specifically excluded Milano’s negligence or other wrongdoing in the supervision, hiring, employment, training, etc. of Krenke, while the “auto exclusion,” in the umbrella policy, did not.

Therefore, the court affirmed the decision of the trial court that no coverage was owed under the commercial general liability policy, but coverage could be owed under the umbrella policy.

As noted, the number of places where umbrella coverage is broader than primary are not many. But Grange Mutual Cas. Co. v. Milano Enterprises demonstrates that there are some – and sometimes it makes a difference.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Surprising: NJ Court Says Insurer Needs Prejudice For Pre-Tender Defense Costs Disclaimer

I have long believed that, based on the New Jersey Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in SL Indus., Inc. v. Am. Motorists Ins. Co., an insurer need not prove prejudice to disclaim coverage for pre-tender defense costs. The SL Industries court concluded that the duty to defend is triggered by facts known to the insurer and “if the insured does not properly forward the information to the insurance company, the insured cannot demand reimbursement from the insurer for defense costs the insurer had no opportunity to control.” That differs from a complete disclaimer based on late notice, where New Jersey has a prejudice requirement. But, in The Lewis Clinic for Educational Therapy v. McCarter & English, LLP, No. Mer-L-747-19 (Sup. Ct. N.J. Civ. Div. Jan. 13, 2020), a New Jersey trial court recently called SL Industries merely “instructive” and concluded that the insurer was required to prove appreciable prejudice -- and it couldn’t.

OCIP Exclusion Applies To Additional Insured – Even If Named Insured Not Enrolled In Wrap-Up Policy

For those who come across wrap-up issues in CD claims, check out Liberty Mutual Fire Ins. Co. v. Southern Owners Ins. Co., 18-81018 (S.D. Fla. Jan. 24, 2020). The court concluded that an OCIP exclusion, in a CGL policy, applied to an additional insured, even though the named insured was not enrolled in the wrap-up policy: The court stated: “P&A Roofing undoubtedly qualified as an additional insured under the Southern-Owners’ policy. However, the policy had an exclusion. And following the same logic as the TNT court, this Court finds that the Southern-Owners’ OCIP Exclusion extends beyond its named insured (S&S Roofing) to its additional insured (P&A Roofing). Based on P&A Roofing’s undisputed enrollment in the Liberty Mutual Wrap-Up insurance program, the OCIP Exclusion in the Southern-Owners’ policy acts as a bar to coverage for P&A Roofing in the underlying state court action.” The court clarified: “The exclusion contains no requirement for S&S Roofing to be enrolled or insured under any such wrap-up insurance program and such requirement will not be read into the exclusion.”

How Strict Can “Four Corners” Be? Really Strict.

In MMG Insurance v. Giuro, Inc., No. 19-0754 (M.D. Pa. Jan. 6, 2020), the court concluded that an insurer could not rely upon a fact outside the complaint to defeat its duty to defend. The decision was under Pennsylvania law. And Pennsylvania is a strict “four corners” state. So why the hubbub? Because the fact that would defeat the duty to defend was one that the insured admitted to. But it was still not permissible to 86 the insurer’s duty to defend: “From a practical perspective we are of course sympathetic to MMG’s [the insurer’s] arguments. In the instant case, a state-court victim-claimant raised allegations that plainly trigger MMG’s duty to defend Guiro under Pennsylvania’s clearly articulated and strictly enforced four-corners rule. Before this Court, however, Guiro has admitted facts which, if true, would seemingly bring the claims outside the scope of the policy and would remove MMG’s duty to indemnify Guiro. As a consequence, this may also relieve MMG’s duty to defend Guiro under its policy terms. Thus, we are tasked with either enforcing Pennsylvania’s four-corners rule as we understand it or carving out an exception which would, in effect, gut the rule entirely. Absent further guidance, we refuse to do the latter. Such an exception, while perhaps logical and more equitable as applied to the case at bar, would also fly in the fact of the aforecited precedent. It is thus not for this Court to make that leap.”

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|