|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

"It's far more fun," Julian McPhillips tells me, to represent those in need than "to defend the wealthy and help them maintain their wealth." The renowned Alabama lawyer got a taste of the latter early in his career as a Wall Street lawyer. But despite the future that the Columbia Law School graduate and Davis Polk associate had in his grasp, McPhillips walked away from it. He returned to his native Alabama and began a career that would earn him the moniker "The People's Lawyer."

Speaking to me from his weekend-home on Lake Martin, outside, coincidentally, Equality, Alabama, McPhillips shared descriptions of his remarkable career taking on "powerful forces." Some of it is recounted in his recently released book "Only in Alabama – More Colorful True Stories From A Lawyer's Life, 2016-2019." It is a follow-up to his 2016 collection of career accounts.

McPhillips, 73, says that "standing up to bullies" is at the heart of legal struggles in Alabama. He makes this point well in his recently-released title. |

|

|

|

| |

The likeable and fast-speaking senior partner at Montgomery's McPhillips Shinbaum, LLP has led an eclectic life. A two-time Ivy League champion wrestler while at Princeton, McPhillips missed-out on making the 1972 Olympics by the slimmest of margins. His home in Montgomery was the three-decade residence of Helen Keller's sister. Two doors down you'll find the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum, which he and his wife, Leslie, founded in 1986. In 2002, McPhillips was defeated in his effort to be the Democratic nominee to challenge Jeff Sessions for his United States Senate seat. Last year, on the fiftieth anniversary of his college graduation, McPhillips published his senior thesis – on the subject of the French Communist Party's role in fighting the Nazis in World War II. The book is a current nominee for a literary award in France.

There is an array of interesting sidelines to Julian McPhillips's life. But, at his core, he is the man who the Associated Press called "The Public Watchdog."

Personal family reasons brought McPhillips back to Alabama in 1975. But despite his New York experience, two years at the white shoe firm and two at American Express, McPhillips didn't pursue a corporate law career. Instead he sent a letter to then Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley and asked for a job.

McPhillips tells me that Baxley was "one of the most dynamic state attorney generals in the country at the time." The job applicant had been "reading and hearing good things about the kind of work he was doing in Alabama on the environmental front, the justice front and taking on corrupt politicians." McPhillips says he "found it attractive" and decided to "give it a crack."

Baxley, in the forward to "Only in Alabama," recalls receiving McPhillips's letter. His interest was piqued, he says, by the letter writer's outstanding academic pedigree, job experience and wrestling accomplishments. But what sealed the deal for Baxley – offering McPhillips a job without even an interview – was his desire to return to Alabama. Baxley writes: "He obviously was willing to make sacrifices, financially and otherwise, to help achieve what he thought was in the public good for our state."

McPhillips served as an Assistant Attorney General for two years. In 1978 he headed for private practice and turned to civil rights. Compared to civil rights unrest in the 1960s, by the mid-1970s, McPhillips says that "things had cooled down a little bit, but not a whole lot. It gave me a lot of opportunities to do some real civil rights work."

McPhillips has spent the past 40 years handling a breathtaking number and wide array of cases, including, in addition to civil rights, employment discrimination, criminal defense, police brutality and wrongful death. Some of his cases, he says, didn't get the publicity of those from other states. "In Alabama we're seen as an outpost," McPhillips tells me. "'What else do you expect.'"

McPhillips says that "a lot of people give me credit that they think I deserve – whether I do or not – for opening up employment opportunities for blacks in state government in Alabama." This started with Reynolds v. Alabama Department of Transportation, which charged the DOT with race discrimination in violation of Title VII. McPhillips also succeeded in striking down, as unconstitutional, Montgomery's vagrancy law in Timmons v. Montgomery. He called it "Montgomery's South Africa law because it was used to harass and arrest poor people, mostly black, who could not identify themselves to police officers with a written form of identification." Much more of McPhillips's work is laid out, in a serious but breezy fashion, in his first collection of career anecdotes in the aptly titled "Civil Rights In My Bones."

The title of McPhillips's latest book is attention-getting. But what does "only in Alabama" mean? And what does it infer? McPhillips tackles this on page one: "Of course, bizarre and strange situations can happen anywhere, so some of the chapters of this book might well have occurred in other states. Yet the sum total of the stories I share here illustrates the case that Alabama is unique – delightfully so in many ways, woefully so in many others."

Ultimately it is difficult to precisely define "only in Alabama." It seems to be a you-know-it–when-you-see-it situation. "There are some things that have happened where you say 'oh my gosh, only in Alabama.'"

McPhillips shares the story of representing Tonya Snow for shoplifting a dress from a department store. That doesn't sound too serious. But Ms. Snow was a habitual offender and facing ten to fifteen years if convicted. There is the story of an attractive bartender entrapped by the Alabama Alcoholic Beverage Control Board into serving alcohol to a minor. Her face was emblazed on the cover of "Booked," a magazine of mugshots of those charged with crimes in three Alabama counties. The caption read "The most beautiful mug shot of 2014. We don't remember what she did."

McPhillps introduces readers to the Anniston, Alabama law firm of Ghee Draper, where he says that "the only nepotism rule is to practice it." The firm's attorneys include name-partner Doug Ghee, four of his daughters and three sons-in-law. McPhillips also shares the story of Montgomery lawyer Tommy Kirk, whose best-in-the-business reputation has earned him the title "King of the DUIs."

While "Only in Alabama" has plenty of lighthearted stories, many of McPhillips's cases are serious business – such as those involving police misconduct and Alabama's prisons. McPhillips also shares accounts of taking on universities, a behemoth insurer, the United States Air Force and First Amendment fights.

The list of powerful forces that McPhillips takes on is not limited to defendants. In the chapter addressing his fight against an insurer, for employment discrimination, McPhillips's criticism of the federal magistrate judge, for preventing him from taking a key deposition, is remarkably unfiltered. "I'm glad that magistrate judge has moved to Birmingham, because I handle a lot more cases in Montgomery than Birmingham," McPhillips tells me.

The cases recounted in "Only in Alabama" are dizzying in their variety. But they share one common trait -- McPhillips's doggedness in the pursuit of justice.

McPhillips calls Helen Keller an enormous inspiration in his work. "She has encouraged me in all my civil rights work, especially for people with disabilities, for blacks, women, immigrants, and any other group or person wrongfully discriminated against or unjustly treated."

But more than just an admirer, McPhillips has a personal connection to the legendary advocate for the disabled. From the 1920s to 1950s, his Montgomery home, in the city's old Cloverdale neighborhood, was the residence of Helen Keller's sister, Mildred. Helen visited often and had a bedroom that would later belong to McPhillips's daughter. It still includes an eight-foot tall, 500 pound chiffonier that had been transferred from Helen's childhood home.

On the home's porch is a 1955 photograph of the Keller sisters sitting in the spot where the picture now hangs. "I can simply sit out on my front porch," McPhillips says, "lean back in the rocking chair where [Helen] once sat, close my eyes, and reflect upon her."

While sitting on his porch, McPhillips is in close proximity to the former bedroom of another national treasure – F. Scott Fitzgerald. For a six-month period between 1931 and 1932, Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, lived in the 8,500 square foot home located two doors down.

In 1986 the Fitzgerald home was slated to be torn down to make way for the construction of 20 town homes. The McPhillipses purchased the home, transferred it to a non-profit corporation and turned it into the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum. It is the only museum in the world dedicated to Jay Gatsby's creator.

While McPhillips says that he'd "always been interested in Fitzgerald," he freely admits that his decision had something to do with the thought of all those new neighbors. "While I like to act like my interest in the museum was completely altruistic, the truth would be that there were some selfish interests involved too."

Through the growth of Fitzgerald artifacts collected over the years, the museum, known as "The Fitz," now occupies almost 5,000 square feet and also includes two apartments – the Zelda Suite and the Scott Suite -- that are rented as Airbnbs. The suites are beautiful and damn – a steal at $80 a night.

It has been a remarkable life for the lawyer with civil rights in his bones. Julian McPhillips's resume could have taken him anywhere. But he returned to his native Alabama. As the saying goes, home is where the heart is. For McPhillips, it can be found in one more place. "My heart is with the little guy." |

| |

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue11

December 18, 2019

Office Holiday Party + Lamp Shade On The Head = Coverage Dispute

|

|

|

|

|

| |

It is one of the oldest gags in the book. Someone is at a party, has too much to drink and puts a lamp shade on their head. But does anybody really do that? Or is it just a joke people make about someone drinking too much?

Well, for sure it happened once. And it didn't end well for the gagster. And, as often happens when people do foolish stuff, enter the lawyers. Enter the insurance claim. Enter the coverage dispute. Enter the DJ action. Enter Randy Spencer.

The Nebraska district court in Mansion on the Hill Hotel, LLC v. Coast City Property & Casualty Company, No. 19-23687 (Neb. Dist. Ct. (Lancaster Cty.) Dec. 2, 2019) tells the tale. It all started on December 10, 2017 at the annual holiday party, held by Highway Industries at the Mansion on the Hill Hotel in Lincoln, Nebraska. Highway is in the business of making the cardboard tubes inside rolls of paper towels and toilet paper. The company boasts that its tubes have been used in over one billion craft projects.

At the party, Joe Roberts, Highway's sales manager, overindulged on purple flip flops – a drink make up of pomegranate juice, pineapple juice, coconut rum and vodka. The combination of pomegranate juice and pineapple juice makes for a lovely purple color. Roberts was ridiculed all night for his choice of beverage. Most people were drinking Tanqueray. By the end of the party Roberts was hammered.

While leaving the hotel, to meet his Uber vehicle, Roberts stopped at a table in the lobby. On it was a lamp with a cone-shaped shade. Roberts joked to his colleagues that he wears a size 9 lamp shade and would see if it fit. Roberts pulled the shade off and put it on his bald head. Unfortunately for Roberts, the shade had a metal ring at the top. On account of the 150 watt bulb just an inch away from it, Roberts suffered a perfectly circular second degree burn on the top of his head. It resembled a halo. Behind Roberts's back his colleagues called him the idiot angel.

Roberts sued Mansion of the Hill Hotel for negligence. He alleged that the hotel failed to warn that the lamp shade contained a burning hot ring that would clearly cause a head burn to anyone who tried it on. Roberts argued that the hotel, because of its heavy volume of holiday parties, knew that the lamp shade in the lobby was as attractive nuisance for intoxicated guests and also knew that the ring at the top was very hot. Thus, Roberts maintained that the hotel had a duty to warn about the risks of putting on the shade. Or the hotel should have only used lamps with permanently affixed shades.

Mansion provided notice of the complaint to Coast City P&C and sought a defense under its commercial general liability policy. Coast City retained John Brown to defend Mansion under a reservation of rights. Coast City then filed an action seeking a determination that it had no obligation to provide coverage to Mansion for any damages awarded to Roberts on account of his injury.

Coast City maintained that no coverage was owed for damages on account of the policy's Holiday Party exclusion, which provided as follows: "This insurance does not provide coverage for any claim arising out of an organization holding a party between Thanksgiving and December 31."

Coast City P&C was aware that the hotel hosted many company holiday parties and did not want to be exposed to lability for events associated with sometimes foolish behavior on account of overindulgence in alcohol.

Coast City and Mansion filed competing motions for summary judgment. The court in Mansion on the Hill Hotel, LLC v. Coast City Property & Casualty Co. held that the Holiday Party exclusion served to preclude coverage for any damages awarded to Roberts on account of his injury.

The court concluded that the exclusion was not ambiguous: "The court agrees with Coast City that there is only one reasonable interpretation of the Holiday Party exclusion. The court reject's Mansion's argument that, because the injury sustained by Roberts took place after the party was over, and outside of the party venue, it was not arising out of an organization holding a party. If Roberts tripped and fell into the Gargoyle fountain in the lobby, the court would have a more difficult task. But Roberts testified at his deposition that he would not have put the lamp shade on his head if not for his many fruity libations, being in the company of co-workers at a party and an alcohol-fueled atmosphere. Roberts's account, of why he used a lamp shade as a fedora, shined a bright light on why his injury arises out of an organization holding a party. While it is not the court's role to address whether the hotel should have taken action to prevent this Christmas story, it may want to use a leg lamp during the month of December."

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Encore: Randy Spencer’s Open Mic

In Re Slipping On A Banana Peel: Real Injury Cases That You Won’t Believe Are Real (But I Swear They Are)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

It is the mother of all proverbial accidents – slipping on a banana peel. Of course it is de rigueur for cartoons. But does this mishap actually happen in real life? University of Memphis Law School Professor Andrew McClurg recently took up this question on his superb legal humor website – lawhaha.com. Professor McClurg's answer -- it does. In fact, the issue has long-been studied by first year law students in what the Professor calls the "famous trilogy" of banana peel cases. And numerous other examples abound. But to make the point, like, really make the point, Professor McClurg posted a Tennessee death certificate, from 1927, stating: "patient fell on banana peeling and fell shortly before death."

So if slipping on a banana peel can be the real deal, I wondered if other common cartoon accidents also take place? I checked. Yes, they do. Consider these other mishaps that made their way from Tom and Jerry to the courthouse:

Dow Drug Co. v. Nieman, 13 N.E.2d 130 (Ohio. Ct. App. 1936) (plaintiff purchased a cigar at a drug store, took it home, proceeded to smoke it and it exploded)

Allstate Ins. Co. v. Furman, 445 N.Y.S.2d 236 (N.Y. App. Div. 1981) (involving coverage for injuries sustained by a child when an anvil fell on his hand)

Perotti v. Seiter, 869 F.2d 1492 (6th Cir. 1992) (plaintiff slipped and fell on a bar of soap while showering and injured his back)

Crovetto v. New Orleans City Park Imp. Ass'n, 653 So. 2d 752 (La. Ct. App. 1995) (plaintiff struck in the head by a golf club that flew from the hands of another golfer who was receiving a golf lesson)

Cerrato v. Carapella, 804 N.Y.S.2d 402 (N.Y. App. Div. 2005) (child injured at a bowling alley when a bowling ball fell from a rack to the floor, and then bounced up and hit him in the face) (Come on, how can that happen?)

Dunn v. Bilger, 1995 WL 230961 (Conn. Super. Ct. Apr. 11, 1995) (defendant attempted to put his bowling ball into a locker, it slipped from his hand and landed on the head of a person putting his own ball into a lower locker).

Jimenez v. Omni Royal Orleans Hotel, 2007 WL 808662 (E.D. La. Mar. 14, 2007) (plaintiff fell into an open manhole while walking down the street)

Faulhaber v. Roberts Dairy Co., 24 N.W.2d 571 (Neb. 1946) (workers compensation claim involving an employee who hit his thumb with a hammer)

Wringer v. U.S., 790 F. Supp. 210 (D. Ariz. 1992) (plaintiff fell through thin ice on a lake)

Parra v. Rieth-Riley Const. Co., 2001 WL 310414 (Tenn. Workers Comp. Panel 2001) (workers compensation claim involving an employee that struck his foot while operating a jack hammer)

Kearns v. Smith, 131 P.2d 36 (Cal. Ct. App. 1942) (landlord not liable for injuries suffered by a tenant who inserted a finger into an electrical socket)

Meehan v. McCloy, 40 N.Y.S.2d 207 (N.Y. App. Div. 1943) (plaintiff injured when a Murphy bed in a room she rented collapsed and struck her)

Johnson v. Outdoor Installations, LLC, 979 N.Y.S.2d 523 (N.Y. App. Div. 2014) (police officer ran into a pole during the lawful pursuit of a fleeing suspect)

Reed v. Western Union Telegraph Co., 141 P.161 (Or. 1914) (a pail of paint fell from the top of a telegraph pole and struck the plaintiff)

Shaggy, as Guardian for Scooby v. The Cairo Museum, 26 P.3d 434 (Cal. Ct. App. 1975) (dog injured when all four of its legs landed in buckets while being chased by a mummy)

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

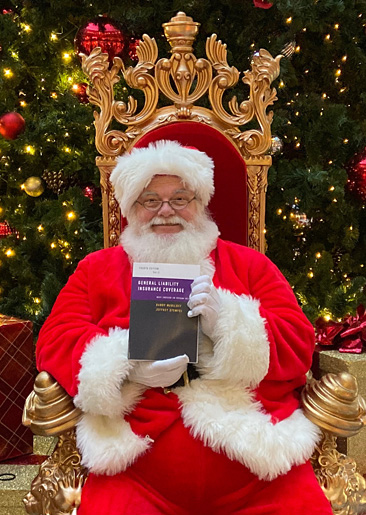

The Beard Is Real!! |

|

|

|

| |

Kids, If you're naughty

this is what you'll get in your stocking! |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

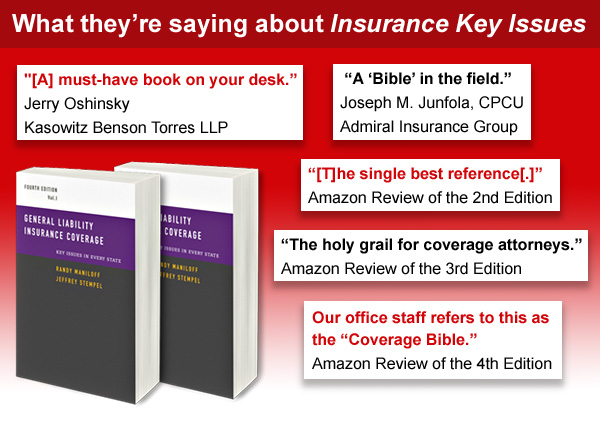

I’m thrilled that Insurance Key Issues was on sale for half-price. Loads of books were sold during the sale period! But just like a box of Dots, all good things must come to an end.

Insurance Key Issues will return to full price on January 1, 2020.

If you’ve been on the fence, or thinking about a second copy for the office, beach house, car or bathroom, now’s the time.

More about Insurance Key Issues and links to purchase on Amazon are here.

http://insurancekeyissues.com |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

This Was Exciting: The Wall Street Journal Published My Op-Ed

|

|

|

| |

As a big fan of the intersection of sports and the law, I was delighted that The Wall Street Journal recently published my op-ed about the widely-reported on-field combat between the Cleveland Browns Myles Garrett and Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph.

In the aftermath of the incident, many wondered if Garrett could be criminally charged for hitting Rudolph in the head with a helmet.

In my WSJ op-ed I addressed this question in the context of cases addressing on-field assaults – taking place away from the play -- by one football player against an opposing player.

I hope you can check it out. Click here.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8, Iss. 11

December 18, 2019

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

[This article appeared in the December 16, 2015 issue of Coverage Opinions. There are lots of new subscribers since then so I decided to repeat it here.]

To an outsider it seems like a simple operation. Not to mention astonishing. Do no advertising. Orders flood in from around the globe. Be loved by everyone. And work just one month out of the year. But the truth is that Santa Claus’s operation is much more complicated and not always so jolly. The amount of things that can, and do, go wrong is legion. Few know this but the bearded one has an insurance program as complex as that of a drug manufacturer.

It wasn’t always this way. “Why on Earth would I need insurance?,” Santa would say to the insurance agents constantly making pitches to him while their kids were bouncing on his lap. “Insurance? Who would sue Santa Clause?,” he would ask incredulously while letting out a big belly laugh.

But times change. In ‘68 some heathens in Philadelphia booed Santa. And two years later someone did the unthinkable and sued Santa. The reindeer came in for a hard landing and damaged a few shingles on a roof. It was minor. But Santa got dragged into court -- mumbling all the way about no good deed going unpunished. After that Blitzen bit off a kid’s finger and the family was pretty frosty. The floodgates were now open. Insurance became one of Santa’s biggest expenses. He stopped delivering gifts to trial lawyers’ houses.

For the past four decades Santa’s insurance has been written by Arctic Insurance Group. But despite all of Arctic’s promises to bail him out of trouble, it has been quite the opposite. Santa’s success at getting claims paid has resembled that of the Cubs. And the reason for this is easy to explain – for the past 33 years Santa’s claims were assigned to the Insurance Grinch. The Insurance Grinch found just about every way possible to disclaim coverage for just about every claim that Santa presented. His skills were unparalleled. When Santa began to get inundated with claims for knocking out Dish Network service with his sleigh, the Insurance Grouch disclaimed coverage on the basis of the aircraft exclusion. Wow! Now that’s impressive.

Good news for Santa -- the Insurance Grinch recently retired. He’s headed to Minnesota to enjoy the warmer weather. He bought a house in a neighborhood with lots of kids so he can tell them to get off his lawn. Even though the Insurance Grinch is not a subscriber – he finds that Randy Spencer column to be annoying -- he agreed to give an exclusive interview to Coverage Opinions addressing a claims career like none other.

Coverage Opinions: Thank you Insurance Grinch for taking the time to discuss your 30+ year career handling Santa’s claims. Were the other adjusters jealous that you handled such a fascinating and unique account?

Insurance Grinch: Very much so. But not because I was handling Santa’s claims. Because it meant that I didn’t have to deal with any construction defect claims.

CO: What was your favorite thing about handling Santa’s claims?

IG: When you put on your Match.com profile for “occupation” that you handle Santa Claus’s insurance claims it makes a lot of people want to meet you.

CO: What was the most common claim from Santa that you handled?

IG: That’s easy. A kid would ask Santa for something – like an iPad. And he’d wake up on Christmas morning and find a sweater. Then, just as day follows night, in rolled the claim against Santa for breach of contract and detrimental reliance.

CO: How did you handle these?

IG: Well, there was no “bodily injury,” “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury” to trigger CGL coverage. And several years ago the North Pole Supreme Court held that, when Santa opens a letter from a youngster, it qualified as the formation of a contract. I know. It’s crazy, right. But it’s a liberal bench up here. But once the court found that an opened letter was a contract, it became easy to disclaim coverage since the professional liability policy has a breach of contract exclusion.

CO: Tell me about that claim where Blitzen bit off a kid’s finger?

IG: The kid was visiting Santa on a school trip and handing Blitzen a carrot. Except the kid was holding it in front of Blitzen’s mouth and the pulling it away. Holding it in front of his mouth and the pulling it away. The kid deserved it. I’m pretty sure Blitzen did it on purpose. At least I hope he did.

CO: Was it covered?

IG: No. We had a reindeer exclusion in all of the policies. I know. It seems strange given that the reindeer are such an essential part of Santa’s operation. But Santa didn’t read the policy. At least not until it was too late. And the broker was asleep at the switch. So we were able to get it in. And we have refused to take it out. We’re the only insurer in the North Pole. So where else is Santa going to go.

CO: What was the most expensive claim that you handled?

IG: One year Santa was in someone’s living room and his toy sack knocked a vase off a table. Turns out it was from the Ming Dynasty. Worth two million. The homeowner’s insurer paid for it. We were sure a subro claim would be made. We kept waiting but it never came in. Word on the street was that the homeowner’s carrier was afraid of the bad press from suing Santa.

CO: Were there any unique liability issues involving Santa?

IG: Many years ago the North Pole Supreme Court held that Santa can be liable for a defective product under the Restatement of Torts 402(A). As you can imagine, this opened Santa up to massive products liability exposure – defective BB guns, Easy Bake Ovens that start a fire, Parcheesi pieces that get swallowed. He was never able to get products coverage after that.

CO: You don’t get too many visitors up here. Seems like Santa’s premises exposure was pretty minimal.

IG: True. Not many make their way here. No direct flights. But that didn’t stop Santa from having premises liability exposure. Santa never shoveled the snow. He blamed a bad back but I think he was just lazy. The mail man would come ten times a day during the busy season and constantly wipe out on ice while walking up Santa’s driveway. Santa knew it was going to happen. Finally we said enough is enough and disclaimed coverage based on no “occurrence.”

CO: Were there are claims that involve Coverage B of the CGL policy?

IG: One in particular. Santa would put a kid on the naughty list. The brat would turn around and sue for defamation. But we were successful in knocking these out of coverage on the basis that there was no “publication” of the kid’s naughty status. The only one who knew was the kid himself when he received the mandatory ten-day notice letter from Santa.

CO: What about the elves. Did they ever cause any trouble for Santa?

IG: Look, this was a big operation. At peak time the elves work 16 hour days. What choice did Santa have? Work the elves to death or disappoint a kid in Cedar Rapids who wanted a fire truck. So of course there were some wage and hour and overtime disputes. But we had an exclusion for this. The elves also got hurt fairly regularly. All the uncovered lawsuits required Santa to cut some corners on safety. Thankfully we didn’t write the comp.

CO: Did Santa ever damage any chimneys? Let’s face it, he’s not exactly svelte.

IG: All the time. But that was an easy one to handle. Those claims fit right into the exclusion for property damage to that particular part of real property on which you are performing operations.

CO: Any other interesting things about Santa’s risk program?

IG: We require Santa to be an additional insured on all of the mall Santa’s policies. Not surprisingly, Santa sometimes gets brought into a suit against a mall Santa who did something stupid. But Santa didn’t police their policies so he was never an additional insured. And we had an exclusion for Santa’s failure to secure AI rights.

CO: I’m starting to wonder – were any claims covered?

IG: Of course. Back in ’98 we paid a claim. Wait. It might have been ’97. A tike fell off Santa’s lap. We looked at everything but just couldn’t find a reason to disclaim. We thought about no “occurrence” since it seemed like faulty work. The kid is supposed to stay on Santa’s lap. He fell off. That sure sounded faulty to me. But in the end we settled and wrote a check. The policy had a pretty low sub-limit for claims arising out of, based on, in connection with or related to kids falling off Santa’s lap.

CO: Have you been training your successor?

IG: I have. But he still has a long way to go. On my last day in the office he got in a claim from a germaphobe family saying that Santa sneezed on their son. The kid is seeking medical monitoring for the rest of his life. The new adjuster was ready to appoint counsel. I said not so fast. Sounds like the pollution exclusion.

CO: What advice did you give to your successor?

IG: I explained to him that the vast majority of the claims come in the door in January and February. If he’s doing his job he’ll have them all disclaimed by the end of March. After that the key is to pretend to be busy for the next nine months.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Adjuster Punished For ROR Letter That Cited 73 Pages Of Policy Language

|

|

|

| |

I’ll be the first to admit that I haven’t read too many literary classics. Sure, I had to read some in high school. But I hated it. I turned to Cliffs Notes in lieu of the heavy lifting.

While literary classics were not my thing in school, and certainly not later in life -- when nobody was making me read them -- it would be a whole different world if our greatest authors had been coverage lawyers and other professionals. In that case, there are several literary classics that would surely be on my shelf. I’ll talk about these over the next few issues. For now let me start with this one.

In The Scarlet ROR Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne shares the story of Hester Prynne, a claims adjuster, who wrote a 74-page reservation of rights letter, for a claim involving a plaintiff who tripped over an uneven pavement in front of a candy store. The letter included 73 pages of verbatim policy language, including provisions from policies that the insured didn’t even have. The letter concludes with “Based on the foregoing, we reserve all of our rights.” You can never be too careful, Prynne tells her supervisor in chapter 2.

The letter was challenged by the insured for not fairly informing it why the insurer, despite providing a defense, may not have an obligation to provide coverage for any damages awarded. The court held that the reservation of rights letter, despite its length, did not meet the “fairly inform” standard. However, the court did not estop the insurer from asserting any coverage defenses. Instead, Prynne was required to wear an R on her shirt until the claim settled.

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Plaintiff’s Lawyer: Show Me The Monet. Court: You’ll Get No Van Dough.

Robert Chemers On The Secret To His Winning Haiku

|

|

|

| |

As reported in the last issue of Coverage Opinions, second place in the Insurance Coverage Haiku Contest went to renowned coverage attorney Robert Chemers of Pretzel & Stouffer in Chicago. Robert’s winning haiku was this gem:

Intentional stabs

Insurer says no cover

Now negligent stabs

Robert shared with me the source of his idea for the haiku. It’s remarkable. It’s one of the best “artfully drafted” complaint cases I’ve ever seen. [This is kinda like Coverage Opinion’s version of VH1’s Behind the Music.]

The haiku had its genesis in Allstate Insurance Co. v. Carioto, 551 N.E.2d 382 (App. Ct. Ill. 1990). The case involved coverage for an insured, Jeffrey Carioto, under a homeowner’s policy, for a personal injury action brought against him by Jenner Evans. Evans claimed that Carioto stabbed him during the course of an armed robbery. Carioto pleaded guilty to attempted murder.

There were several issues before the court. But the one giving life to the haiku was this. Allstate filed an action seeking a declaratory judgment that it was not obligated to defend or indemnify Carioto because of an intentional acts exclusion.

Allstate moved for summary judgment and it was granted. Evans appealed and argued that the coverage action was premature because the “question of Carioto’s intent was an ‘ultimate fact’ yet undetermined in the pending tort action.”

The appeals court acknowledged that, while insurers are encouraged to file declaratory judgment actions to address coverage issue, “in instances where bona fide controversies arise over the issue of negligence versus intentional conduct, declaratory judgment actions are generally inappropriate.”

But, despite this general rule, the court concluded that a bona fide controversy did not exist in the matter at hand, since “the insured’s conduct, a criminal conviction resulting from that conduct, and judicial admissions made by the insured, together provide conclusive evidence that the conduct was intentional.” In essence, the evidence of intentional conduct was overwhelming.

Here is where it gets interesting. Evans, seeing the coverage challenges on account of the intentional acts exclusion (to say the least), drafted an amended complaint that was obviously designed to implicate Allstate. This is certainly not unusual. Plaintiff’s lawyers, in cases involving intentional torts, often draft complaints to include allegations of negligence. Since the duty to defend is tied, at least, to the allegations in the complaint, their hope is that the insurer -- which must treat the allegations as true, even if groundless, etc. – will be forced by the negligence allegation to acknowledge a defense obligation.

Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t. In some cases, the allegations against the insured so clearly involve intentional conduct, that the court rejects the negligence allegations, despite the rule that the allegations in the complaint control. Essentially, the court is saying that it will not allow itself to be snookered into concluding that a defense is owed, when it knows the real story, and knows that the complaint was “artfully drafted” -- a term that some courts use – to trigger a defense.

That’s what happened in Carioto. But here, the artfulness of the complaint drafting was some of the best I’ve ever seen. The complaint is museum worthy. In concluding that there was no bona fide controversy, that Carioto’s actions were intentional, the court described the plaintiff’s lawyer’s masterpiece:

“In this case, the nature of the assault against Evans, and the initial allegations made by Evans in his suit against Carioto, are certainly consistent with Allstate’s contention that Carioto’s conduct was intentional. The complaint filed against Carioto on February 25, 1983, was for assault committed willfully and maliciously with force and arms against Evans. There is no question that such conduct is excluded under the Allstate homeowner’s policy. Two and one-half years later, the third amended complaint alleged that Carioto’s actions were merely ‘careless and negligent’ in ‘falling on’ or ‘failing to avoid’ or ‘negligently striking’ Evans. We find these allegations facetious, given that Carioto announced his intent to stab Evans; brandished his knife in order to effect the robbery; after receiving the object of the robbery, Evans’ money, joined his accomplice in the struggle on the ground; and stabbed Evans 17 times even after his accomplice withdrew.”

The plaintiff’s lawyer artfully drafted a complaint so that Allstate would show it the Monet. But the court was just not convinced that the insurer must pay any van Dough.

As Robert Chemers said:

Intentional stabs

Insurer says no cover

Now negligent stabs

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Coverage Opinions “Hormone Hunter” Story Reprinted By The Savannah Bar Newsletter

|

|

|

| |

I had so much fun getting to know Savannah lawyer Arnold Young while putting together an article in the last issue about his former colorful partner, Colonel E. Ormonde (“Hormone”) Hunter. Arnold brought Hormone Hunter to my attention when he shared with me that the Colonel once handled a case -- 1954 -- where he obtained coverage for property damage caused by a squirrel.

The Colonel’s argument was that the squirrel could not possibly be “vermin,” for purposes of a policy exclusion, when it has “long been well considered and much thought of as a pet and an attractive addition to the scenery of any city, garden, or country yard” and praised as a “shining example to mankind of industry and thrift.” [I love this part about the Colonel giving the squirrel credit for the lesson it teaches from collecting acorns for the winter.]

I was delighted when Arnold informed me that The Citation, the Savannah Bar newsletter, reprinted the Hormone Hunter story. You can check it out here.

I’ve never been to Savannah (my loss). I need to do that. My wife has mentioned it. I’ve always wanted to see the Bird Girl statue that appears on the cover of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Arnold assured me that there’s lots more than that to see and do in Savannah and that, even as a Yankee, I’d be warmly welcomed – so long as I promise to think and speak right!

Thanks again to Arnold for sharing The Citation reprint with me.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

OMGosh: Look Whole Stole Coverage Opinions

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

ISO Introduces Several New Additional Insured Endorsements

Saxe, Doernberger & Vita Provide A Summary

|

|

|

| |

A lot of law firms send email blasts about new coverage decisions. I’ve long been a fan of the ones that come from Connecticut’s Saxe Doernberger & Vita. They write about interesting and relevant topics and get their blasts out very soon after the decision. They are often the first to report on it. Quite simply, when it comes to new case blasts, they do it right.

The firm handles a lot of additional insured cases. So it is no surprise that SD&V wrote the first article that I’ve seen that addresses several new additional insured endorsements issued by the policy drafting gang at ISO (effective December 1). The endorsements cover several areas, but, of course, a substantial impact will be felt in the context of construction-related injuries and damages.

It will be a long time -- a really long time -- before these endorsements make their way into decisions. It’ll take a while for many insurers to adopt them -- years in fact, if ever, for some. Then there need to be disputes, litigation and decisions. For now, they are more relevant for underwriters in deciding the scope of AI coverage to be offered.

Here is SD&V’s explanation of the new ISO AI endorsements:

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Warning Sign: Don’t Get Sucked-In

|

|

|

| |

I came across this beauty of a warning sign on a flight not long ago. I love that sucking noise that the airplane toilet makes when you flush it. The power is awesome. It’s hard to imagine anything it won’t take down. Yikes, I’m afraid to think about the impetus for this warning sign!

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

9th Circuit Rules In The Case Of the Century

|

|

|

| |

It was billed as “The Fight of the Century.” The hype was insane. And so were the ticket prices. But in the end, the May 2, 2015 fight in Las Vegas, between Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather, was a dud. The Los Angeles Times called it “a yawner.”

The fight went all twelve rounds and Mayweather won. Afterwards, it was learned publicity that Pacquiao had suffered a serious shoulder injury a month before the fight. So, as is wont to happen, lots of putative class actions were filed by pay-per-view customers, ticker purchasers and others who lost money against the fighters, promoters and broadcaster, HBO. Indeed, an MDL was created for the suits.

The theory of liability, as the court described it: “Plaintiffs contend that Defendants’ failure to reveal Pacquiao’s injury was deceptive and misleading, which deprived the public of the ability to ‘make an informed purchasing decision . . . based on all material facts.’ They claim that they would not have purchased their tickets, PPV, or closed-circuit distribution packages if Defendants had not made ‘misleading . . . statements related to’ or omitted material information regarding Pacquiao’s physical condition. Plaintiffs contend that the public ‘would naturally believe—as they had been led to believe—that they were purchasing the right to see a contest between highly-conditioned, healthy athletes in peak physical condition and not suffering from any disability or serious injury.’”

The district court knocked out the plaintiffs. The Ninth Circuit recently affirmed. In Alessi v. Mayweather (In re Pacquiao-Mayweather Boxing Match Pay-Per-View Litig.), No. 17-56366 (9th Cir. Nov. 21, 2019), the court noted that “[a] majority of courts that have considered claims brought by dissatisfied sports fans follow what is known as the ‘license approach.’ Under that approach, a ticket holder enjoys only the right to view the ticketed event, and therefore no cognizable injury arises simply because the event did not meet fan expectations.”

|

|

|

| |

In affirming the district court’s dismissal, the appeals court reviewed lots of cases brought unsuccessfully by unhappy fans. Given these cases, the plaintiffs knew that they underdogs in the litigation, but argued that their situation was different, from the typical disappointed fan case, since they were allegedly “defrauded consumers.”

The appeals court did not agree:

“Plaintiffs in this case paid to see a boxing match between two of the top fighters in the world, Mayweather and Pacquiao. Each was medically cleared to fight by NSAC physicians before he entered the ring. Ultimately, a three-judge panel declared Mayweather the overall winner of the match, but each of the judges declared Pacquiao the winner of between two and four rounds. And although the match may have lacked the drama worthy of the pre-fight hype, Pacquiao’s shoulder condition did not prevent him from going the full twelve rounds, the maximum number permitted for professional boxing contests. (citation omitted). Plaintiffs therefore essentially got what they paid for—a full-length regulation fight between these two boxing legends. . . . Whatever subjective expectations Plaintiffs had before the match did not negate the very real possibility that the match would not, for one reason or another, live up to those expectations.”

The court was also concerned with a slippery slope: “We note also that in seeking to hold Defendants liable for alleged omissions and misrepresentations regarding Pacquiao’s physical condition, Plaintiffs theory of liability is potentially boundless. The nature of competitive sports is such that athletes commonly compete—and sometimes dramatically win—despite some degree of physical pain and injury. Taken to its logical extreme, Plaintiffs’ theory would require all professional athletes to affirmatively disclose any injury—no matter how minor—or risk a slew of lawsuits from disappointed fans.”

I’m curious what would have happened if Pacquiao got KOed in the first round and it was because of his bad shoulder. |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

What A Great “Use Of An Auto” Case

|

|

|

| |

I’ve said this many times on these pages – I love “use of an auto” cases (addressing the triggering an Auto or UM/UIM policy or the applicability of a CGL or homeowner’s policy’s auto exclusion). They have a way of involving strange facts. See Roque v. Allstate Ins. Co., Colorado Court of Appeals (2012): (exiting your car and hitting another motorist with a golf club did not qualify as use of an auto for purposes of a UM policy).

That such coverage case curiosities exist is not surprising. After all, we all know what it means to use an auto. So, if “use of an auto” is being litigated, then it’s probably because the claim involves a car or truck and something out of the ordinary.

Such is the case in Deutsch v. Geico General Ins. Co., No. 4D18-2714 (Ct. App. Fla. Oct. 30, 2019). To be technical, this is not a “use of an auto” case in the purest form. However, it is very similar, and, in fact, the issue arises.

The story goes like this:

“Garrett Nodell owns and operates Mobile Fitness Centers of America, Inc., a mobile gym that operates out of the back of an Isuzu truck. To train his clients, Nodell drives the gym to a client’s location and conducts workouts in the back of the truck. The gym is equipped with exercise machines and equipment, some of which are bolted to the floor of the truck. The gym is powered by either a generator or by Nodell plugging into the client’s electricity.

For several years, Natalie Deutsch trained with Nodell. Her training sessions took place in the back of the truck while it was parked near her home and plugged into her home’s electricity. According to the complaint, as a result of Nodell’s negligence during training, Deutsch suffered permanent injuries.

Deutsch sued Nodell and Mobile Fitness Centers and those suits were settled. She also sued Geico, her auto insurance carrier, contending that the mobile gym was an uninsured/underinsured auto under her policy.”

First of all, how do you work out in the back of an Isuzu truck? I bet you are wondering that. I was. So I Googled it and it turns out that mobile gyms are, well, a thing. At least I found some websites for such businesses and some pictures of the retrofired vehicles. I understand that, having the gym come to you, is time saving. But, if you really want to be efficient, why not work out in the mobile gym while it is driving you to the office?

In any event, at issue before the Florida appeals court was whether a mobile gym was an uninsured/underinsured auto under an auto policy?

The definition of an “uninsured auto” excluded from its terms “a land motor vehicle . . . located for use as a residence or premises.”

The trial court found for Geico, concluding that the mobile gym was not an uninsured auto. On appeal, Deutsch argued that the mobile gym was not a premises, because it is not a house, building or tract of land. Therefore, Deutsch argued that the mobile gym did not come within the “premises exception” to the definition of “uninsured auto.”

But the Florida appeals court was not buying it:

“It is true that the truck is not a house, a building, or a tract of land. Under the Geico policy, the central inquiry is not whether a truck is real estate, but whether the truck was ‘located for use as a . . . premises,’ which Harrington defines as a ‘building, along with its grounds.’*** [C]lients worked out in the mobile gym only when it was stationary, parked, and connected to a power source. The clients never worked out when the gym was being driven as a vehicle. When used as a gym, the stationary truck was ‘located for use as a’ building, just as any gym in a strip mall. Because the truck was being used as a ‘premises’ when the negligence occurred, it was not an uninsured auto under the policy.” (emphasis in original).

By concluding that the mobile gym was not an “uninsured auto,” the court did not need to reach the question whether the injuries arose out of the use of a vehicle. But, as you can see, Deutsch v. Geico is a very close cousin to a “use of an auto” case. I love “use of an auto” cases.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Court Says Insurer’s Coverage Letter Is Deficient:

Lessons From The “50-Item ROR Checklist”

|

|

|

| |

This year I visited insurers across the country putting on my seminar titled “The Definitive Reservation of Rights Checklist: 50 Things that Every ROR Should Have.” I traveled far and wide, from sea to shining sea, doing the seminar 13 times. I have it down cold.

[Let me know if you’d like me to stop by your office in 2020 to do the seminar. We can discuss it.]

A recent decision from a federal court in North Carolina addressed a few of the key points that I make in the ROR Checklist seminar.

In DENC, LLC v. Phila. Indem. Ins. Co., No. 18-754 (M.D.N.C. Dec. 5, 2019), the court took issue with certain aspects of an insurer’s disclaimer letter. The decision has several parts and the insurer in fact prevailed on many issues.

On the issue of the disclaimer letter, the court examined whether it violated N.C. Gen. Stat. § 58-63-15(11)(n) [part of the state’s Unfair and Deceptive Trade Practices Act], which requires an insurer to “promptly provide a reasonable explanation of the basis in the insurance policy in relation to the facts or applicable law for denial of a claim or for the offer of a compromise settlement.”

In essence, this is the “fairy inform” standard that many court’s say an insurer must satisfy when drafting a reservation of rights letter. The letter must adequately explain why an insurer is providing a defense, but, nonetheless, may not have any obligation to provide coverage to its insured for any damages. To do so, the letter must tie the facts to the policy language when explaining why coverage for damages may not be owed. It is not enough to simply set out policy provisions on their own. The facts that could support the applicability of such provisions must be included.

The court held that the North Carolina statute had been violated. The basis was its decision that the letter had the following deficiencies:

“Nothing in the denial letter links ‘the basis in the insurance policy’ for the denial ‘to the facts,’ as required by § 58-63-15(11)(n). The letter does provide a detailed summary of the findings of the inspector it hired, but nowhere are those findings ‘related to’ the policy language. Instead, Philadelphia simply repeats verbatim several pages of what purport to be policy excerpts, and then notes—without explaining how these policy excerpts apply individually or in combination—that Philadelphia will deny coverage because ‘the damage is reportedly the result of long-term water intrusion and deteriorated wood framing,’ arising from construction issues. There is no citation of any policy provision that uses the phrase ‘water intrusion,’ or that otherwise links water intrusion and deteriorated wood framing to the language of the policy, and no explanation of why ‘long-term water intrusion and deteriorated wood framing’ are not covered losses. The narrative does not address at all the question of coverage or exclusion under the collapse provisions.

Moreover, some of the provisions set forth in the letter were not even part of the policy; several had been deleted and superseded by policy amendments or endorsements. Others patently do not apply to the breezeway collapse at issue, such as those citing flood or steam boilers, and the wrong provision governing collapse was included.”

The decision addresses three of the issues that I discuss in the ROR Checklist seminar: (1) meeting the “fairly inform” standard; (2) not citing policy provisions that are not relevant to the claim; and (3) being sure that policy provisions cited are the correct version.

[There are 47 other things on the ROR Checklist. Let me know if you’d like me to stop by your office in 2020.]

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Remarkable Duty To Defend Test = Insurer Has Duty To Defend Insured For Sex Trafficking Claims

|

|

|

| |

On one hand, it wasn’t entirely shocking that the court in Ricchio v. Bijal, Inc., No. 15-13519 (D. Mass. Nov. 22, 2019) concluded that the insurer had a duty to defend its insured, a motel owner, for claims that it violated the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (“TVPA”). After all, the victim’s complaint against the insured alleged false imprisonment, which is specifically included in the general liability policy’s definition of “personal and advertising injury.” But how the court got there was finger-in-a-socket worthy.

It was not alleged that the insured itself engaged in sex trafficking. The insured’s involvement was as follows. Lisa Ricchio alleged that she was kidnapped by Clark McLean. She alleged that McLean brought her to the Shangri-La Motel in Seekonk, Massachusetts and held her captive there for a period of several days. The hotel was owned by the insured, Bijal, Inc.

Ms. Ricchio alleged that “she was repeatedly raped and abused by McLean during her captivity, and that McLean made clear to her that he intended to force her to work as a prostitute under his control. She further contends that Bijal and the Patels [who lived and worked at the motel and insureds] were aware of the abuse and profited from it.” It was alleged that Bijal violated the TVPA by receiving rental income for the motel room.

Putting aside several issues, and getting to the heart of the matter, the insurer argued that, despite the policy’s definition of “personal and advertising injury” including false imprisonment, coverage was precluded by the policy’s exclusion for personal injury “arising out of a criminal act committed by or at the direction of the insured.” The insurer argued that Ms. Ricchio’s injuries were caused by criminal violations of the TVPA.

The court’s decision is a little hard to follow, but I think it went like this.

The court observed that “it is possible for a defendant to be civilly liable [under the TVPA] without having violated any of the criminal portions of the TVPA, because the statute permits recovery under a civil standard even in the absence of proof of intentional conduct.”

But, despite this, the complaint still alleged only intentional conduct, such as the following:

They [the Patels and Bijal]:

“knowingly benefitted from participat[ing] in [] McLean’s venture, knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that the venture was engaged in the providing or obtaining of [] Ricchio’s labor or services by means of [] force . . .” in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1589.

“knowingly harbored [] Ricchio at the Shangri-La Motel,” “knowingly benefitted from participation in [] McLean’s venture which they knew or should have known was engaged in an act in violation of the TVPA” and “aided and abetted [] McLean’s violations of 18 U.S.C. § 1590(a).”

The court acknowledged that, while “each of Ricchio’s claims includes allegations of criminal conduct by the Patels . . . the complaint is ‘reasonably susceptible’ to an interpretation finding only negligence.”

But how can that be? How can allegations of criminal conduct be reasonably susceptible to an interpretation that negligence is alleged? Here’s how:

“[T]he Court is not bound to presume all allegations are perfectly accurate as pleaded in assessing the possibility of coverage; a ‘rough[] sketch’ of a covered claim will do. Second, it is commonplace for allegations in a complaint to outline only one, relatively extreme, version of events. The fact that the complaint alleges intentional conduct does not preclude an interpretation that it also includes lesser allegations of negligent conduct. That approach accords with the Massachusetts duty to defend standard that requires only a ‘general allegation’ susceptible to a ‘possibility’ of liability insurance coverage.”

Thus, the court held that the insurer had a duty to defend.

Based on this rationale, an insurer that disclaims coverage, based on a complaint’s allegations of intentional conduct, is at risk of being incorrect since, despite the complaint’s allegations of intentional conduct, there may be another version of events that does not involve intentional conduct. The plaintiff may have only pleaded the “relatively extreme version of events.” The court, in making its duty to defend decision, may consider another possible version.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

That Other Type Of “Property Damage”

|

|

|

| |

Most of the time, when a claim is about “property damage,” nobody is really fussing about the property damage part. In other words, while there may be coverage issues in dispute, one of them is probably not whether the collapsed building or contaminated soil is “property damage.” We know it’s “property damage” because we can see with our eyes that (1) it’s property; and (2) it’s damaged.

But there’s another type of “property damage.” And this kind is not always so obvious. The standard definition of “property damage” includes, in addition to “physical injury to tangible property” -- the kind that’s easy to see -- “loss of use” of tangible property. And that’s loss of use of tangible property that has been physically injured and loss of use of tangible property that has not been physically injured.

The “loss of use” kind of “property damage” gets nowhere near as much attention as its cousin, the physically injured. But, ironically, while the standard definition of “property damage” includes 65 words [not counting the electronic data bit], only 5 of them are applicable to physical injury-based “property damage.” In other words, 85% of the definition of “property damage” is focused on the less common “loss of use” component.

While “physical injury to tangible property” can usually be seen or measured – which is why it’s usually not a source of squabble -- it is not always the same for “loss of use”-based “property damage.” Whether property has been damaged, because it has sustained a “loss of use,” can be esoteric and not have a visibility component. Is loss of value “loss of use”? Are lost profits “loss of use”? These questions can lead to disputes.

The can-be squishy nature of “loss of use”-based “property damage” was on display in Scottsdale Insurance Company v. Darke, No. 19-2225 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 22, 2019).

At issue in Darke was coverage for a landlord, for a suit brought by tenants, who alleged that they had been displaced from their apartment because of its horrific conditions – no heat, no hot water, mice and rats, ceiling leaks and inoperable security bars on the windows. The landlord ignored the city’s requests that it make repairs. The city eventually “red-tagged” the property because it was not zoned for residential use and not habitable.

The landlord, the Darkes, sought coverage under general liability policies. At issue was whether the complaint alleged “property damage,” based on “loss of use of tangible property not physically injured,” on account of the allegations that the tenant was forced out of her apartment because it was zoned for commercial and not residential use. [The claims for constructive eviction were barred by a habitability exclusion.]

The court concluded that it was bound by the California Court of Appeal’s 2007 decision in Golden Eagle Ins. Corp. v. Cen-Fed, Ltd., that loss of use of a leasehold interest is not loss of use of tangible property. In Golden Eagle, the court concluded that loss of rental income, and loss of use of leased space, is not loss of use of tangible property, as leasehold interests are not tangible property.

Darke is not a long decision. And it’s thin in the way of analysis. For sure, there are umpteen better cases out there for demonstrating the challenges that can come from determining whether there has been “loss of use” of property. But it makes the point that, when it comes to “property damage,” there is more than just the kind that can be readily seen.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 8 - Issue 11

December 18, 2019

Holy Palsgraf: Appeals Court Concludes That Auto Accident Could Have Caused Overdose Of Drug

|

|

|

| |

Except for certain unusual situations, I do not do auto coverage work. And I know that many CO readers can say the same. But I included Thompson v. State Farm Mutual Auto Ins. Co., No. 18-1422 (10th Cir. Nov. 29, 2019) here because it’s interesting, causation of injuries is an issue that can arise under various policy types and it involves the prevalent issue of opioids.

At issue was underinsured motorist coverage for Cynthia Thompson. In August 2013, Ms. Thompson suffered a broken neck when her vehicle, in which she was a passenger, was hit by an underinsured vehicle. Here doctors prescribed oxycodone and diazepam to alleviate her pain. Ms. Thompson died six months later.

The autopsy detected no oxycodone in Ms. Thompson’s blood. Instead, fentanyl and diazepam was found. The cause of death was an accidental overdose of this combination of medications.

It turns out that, years before the accident, Ms. Thompson’s doctors prescribed her fentanyl to treat neck pain. She last received a prescription for fentanyl three years before the accident.

It was figured out that “Ms. Thompson used a leftover fentanyl prescription as a substitute for the oxycodone because the oxycodone caused extreme nausea. But because she was no longer a regular fentanyl user, she lost her tolerance to it, and the combination of fentanyl and diazepam proved deadly.”

Ms. Thompson’s son sought UIM benefits from State Farm. But the insurer refused on the basis that the car accident did not cause his mother’s overdose and resulting death. He sued State Farm. State Farm argued that “Ms. Thompson’s self-medication, not the car crash, proximately caused her death. In other words, State Farm argued that her self-medication intervened to break the chain of causation. State Farm claimed it could not foresee that a car accident might cause Ms. Thompson to overdose on a medication that doctors last prescribed in 2010—some three years before the accident.” (emphasis added).

The district court agreed with State Farm. But the Tenth Circuit reversed, concluding that Ms. Thompson’s death could have been caused by the motor vehicle accident:

“As we see it, reasonable minds could disagree as to whether Ms. Thompson’s overdose on pain medication was foreseeable. Plaintiff’s expert opined that ‘Ms. Thompson’s manner of death is consistent with that of an accident via what appears a self-directed attempt to control her pain to prolonged healing of traumatic cervical spine injury.’ Plaintiff also presented evidence that Ms. Thompson had a prior prescription for fentanyl and that she used fentanyl patches to treat neck pain for many years before the car accident. Plaintiff explained that Ms. Thompson replaced the oxycodone with a leftover fentanyl patch because the oxycodone caused her to experience extreme nausea. The district court accepted Plaintiff’s evidence but concluded that Ms. Thompson’s use of a dangerous narcotic was unforeseeable as a matter of law. In reaching this conclusion, the district court failed to adequately consider the context of the situation and draw all inferences in Plaintiff’s favor. As the record demonstrates, Ms. Thompson successfully used fentanyl patches in the past to alleviate her neck pain. Then, after suffering a broken neck in the car crash, her neck pain returned. Plaintiff presented evidence that Ms. Thompson stopped using the prescribed oxycodone because it made her sick and instead used a leftover fentanyl patch—a medication she used (with a prescription) in the past to treat a similar, if not identical, type of pain. A reasonable jury could conclude that based on her medical history and prior use of fentanyl patches, it was reasonably foreseeable that she would use a leftover patch to treat her resurfaced neck pain after the accident. The district court’s conclusion creates a bright-line rule that automatically cuts off causation whenever a person overdoses on non-prescribed or leftover medication. Under Colorado law, however, the fact-intensive nature of proximate causation and foreseeability cautions against such a bright-line rule.”

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Liquor Liability Exclusion Does Not Make Bar’s Policy Illusory

It is not unusual for a policyholder, denied coverage, to argue that it never had a chance, as its policy is illusory. This usually happens when the claim at issue involves a risk that is fundamental to the insured’s business. As the insured sees it, if the policy does not provide coverage for something at the heart of why the insured needs the policy, then it provides no coverage at all. Hence, it is illusory. These arguments are routinely rejected by courts on the basis that, while the policy may not provide coverage for an important risk, it provides coverage for other potential hazards. So, since it provides some coverage, it is not illusory.

This is why the court rejected an insured-bar’s illusory coverage argument in AIX Specialty Ins. Co. v. Members Only Management [OMG – remember those jackets that everyone had], No. 19-12110 (11th Cir. Dec. 11, 2019), after its claim for coverage, for a dram shop action, was denied on account of an Absolute Liquor Liability exclusion in its general liability policy (broader than the standard ISO liquor liability exclusion).

As Members Only saw it, since it is a club that permits patrons to bring in alcohol, “any claim for bodily injury could theoretically bear connection to alcohol, and thus be barred under the Absolute Liquor Liability Exclusion.” But the court rejected the illusory coverage argument for the same reason other courts have – others risks could still be covered: “The exclusion here would not swallow every claim for bodily injury. Imagine, for instance, that a sober patron tripped in a dimly lit corridor and sued for negligence. That claim has nothing to do with alcohol. Or say a light fixture falls from the ceiling and hits a sober patron. That claim bears no connection to alcohol either. No doubt, the Absolute Liquor Liability Exclusion is a significant exclusion given Members Only’s business. But it does not swallow its coverage whole.”

An Oldie: Court Addresses “Occurrence” Defined As An “Event”

For a long time, the definition of “occurrence” in a commercial general liability policy has been “an accident, including continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harmful conditions.” But back in the day, the definition of “occurrence” wasn’t always so standard. In Superior Water v. Certain Underwriters at Lloyds, No. 2018AP1926 (Wis. Ct. App. Nov. 19, 2019), the Wisconsin appeals court addressed 1970 policies, in the context of a claim for environmental property damage, that defined “occurrence” to mean “one happening or series of happenings arising out of or caused by on event taking place during the term of this contract.” If you have this issue you’ll want to check out Superior Water. The court concluded that the term “occurrence” was ambiguous and applied the interpretation advanced by the insured.

Should Breach Of Contract And Bad Faith Claims Be Bifurcated?

For a fairly detailed look at whether breach of contract and bad faith claims should be bifurcated, at least under Pennsylvania law, check out Ferguson v. USAA Gen. Indemnity Co., 19-401 (M.D. Pa. Dec. 5, 2019). The answer – no. “Having found resolution of Plaintiffs’ breach of contract claim is not a pre-requisite to evaluating their bad faith claim, this begs the question of whether the distinctness of the claims supports severing them. The court finds it does not. While the two claims are conceptually distinct, they are ‘significantly intertwined’ from a practical perspective. [citation omitted] For example, one facet of Plaintiffs’ bad faith claim is that Defendant did not, in good faith, attempt to settle Plaintiffs’ claim because it conducted an inadequate investigation into the extent of the insured’s injury. This requires discovery regarding two underlying facts: (1) what was the nature of Plaintiffs’ injuries; and (2) what efforts did the insurer make to investigate Plaintiffs’ injuries. To prove damages regarding their breach of contract claim, Plaintiffs will have to provide similar facts, and Defendant is likely to test them through discovery. As such, separating out the claims and staying discovery would potentially create a discovery mess, requiring truncated depositions, interrogatories, and requests for production, only to have them all re-started following the conclusion of the first leg. This risk of judicial inefficiency warrants denial of Defendant’s request.”

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|