|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

I had the thrill of interviewing James Patterson, the world’s best-selling author, about his recently released book, The Defense Lawyer. It tells the story of Barry Slotnick, the New York criminal defense attorney who achieved renown for securing acquittal after acquittal in some of the city’s highest-profile cases. Slotnick even had a dozen-year stretch in which he didn’t lose a case.

Once called the best criminal lawyer in the country by American Lawyer, Patterson recounts one story after another of Slotnick-abracadabra to keep his clients out of prison. How Slotnick did it is remarkable.

I hope you can check out the interview that I did for the ABA Journal:

https://www.abajournal.com/columns/article/novelist-james-patterson-tells-the-stranger-than-fiction-story-of-criminal-defense-attorney-barry-slotnick

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Declarations: The Coverage Opinions Interview With Stephen And Barbara Gillers

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

ISO Should Commemorate The 50th Anniversary Of The Release Of “The Godfather”

|

|

|

|

|

| |

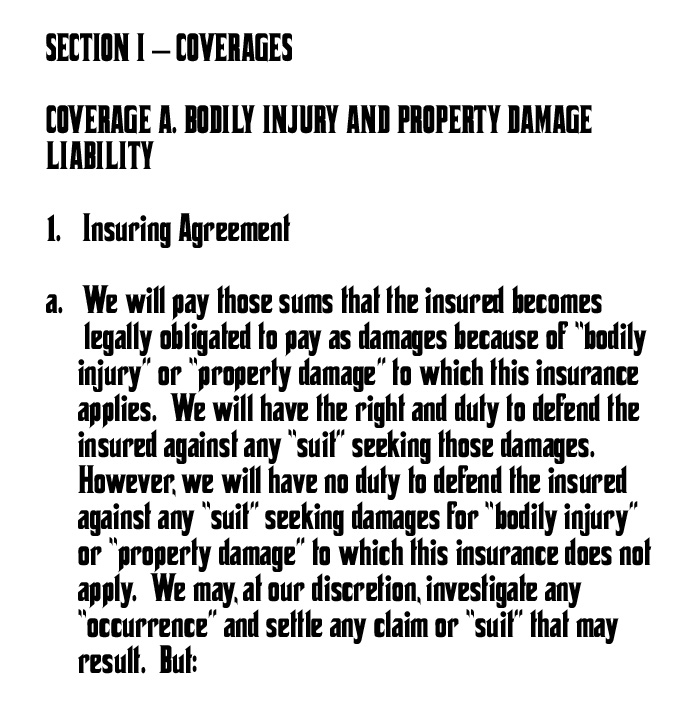

March 14, 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the release of the movie “The Godfather.” Tributes to this movie classic will abound. ISO should pay its respects by releasing a special edition Godfather-font version of its CG 00 01 form. After all, the film’s most famous line – and one of the most iconic in movie history – is used in coverage disputes all the time:

I’m gonna make him a settlement offer he can’t refuse.

|

| |

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Encore: Randy Spencer’s Open Mic

Elvis Is Alive Leads To E-Mail SpoofingAnd Crime Coverage

|

|

|

|

|

| |

This “Open Mic” column originally appeared in the April 30, 2019 issue of Coverage Opinions.

Happy 87th birthday Elvis (January 8, 2022) |

| |

Richard Billings, of Minot, North Dakota, was considered, by those who considered such things, the nation’s leading expert on proof that Elvis Presley was still alive. Billings had spent decades unearthing evidence that he believed established that the King faked his own death on August 16, 1977. Billings had a website that contained photos, voice recordings (with voice analysis experts), DNA evidence, witnesses accounts to Elvis sightings and other information that he believed established that Elvis did not leave this earth in 1997. Billings also had confidential information, from those very close to Elvis, that the star was burned out, felt trapped by his celebrity and simply wanted a simpler life. The only solution was to lead the world to believe that he had forever left the building.

On January 17, 2018, Billings received an email from earonp@gmail.com that read as follows:

Dear Richard,

I have long been impressed by your work establishing that Elvis Presley did not die at Graceland on August 16, 1977. I can tell you, with absolute certainly, that you are correct. I am Elvis Presley. The reasons why I did what I did are complex, but the theory is generally right – my celebrity had taken over my life. I could not do even the simplest things without a mob scene and security. I was a prisoner in Graceland.

After my “death” I changed my appearance as best I could and stayed hidden at various safe houses around the country that Vernon had arranged. I needed some time to pass for “Elvis” to fade into the background of the public’s mind. Vernon also arranged for my identity to be changed and he secretly provided for the lifetime of money that I would need. Slowly I emerged into the world as a real person. I finally had the freedom to live as I wanted. I got to play racket ball (I missed my private court in Graceland J), joined a bowling league and took assorted jobs. I just wanted to have conversations with people that were not about “Elvis.” I wanted friends who I knew had sincere intentions and not simply to be in the entourage.

I eventually settled in Las Vegas where I went to work as an Elvis impersonator. I served as a witness to weddings, did appearances at conventions and performed in shows at some of the casinos. It was a long way from my performances at The Hilton. But this is the life I wanted. I usually got high marks as an “Elvis.” Some folks provided me with advice on things I could do to improve. It was always good fun.

Richard, I need your help. The money that Vernon arranged is close to running out. I am now 84 and too old to work. I need $25,000 to sustain myself. My needs are very simple. That amount of money would go very far. I know that this is a lot of money. All I can do in return is promise you that I will spend the rest of my days with your kindness in my heart. If you can do this please wire the money to the following account: [redacted]. Thank you. Thank you very much.

God bless you,

Elvis

Richard Billings read the e-mail dozens of times. While he understood that it could be a fraud, he could not get out of his mind that the sender’s email address was earonp@gmail.com. Elvis considered his middle name to be Aron, spelled with one “a” only. This, Elvis did, as a tribute to his twin brother, Jesse Garon, who died stillborn. Despite this, the public spelled Aaron the Biblical way. Even Elvis’s tombstone is spelled Aaron.

Richard could not believe that a scammer would know to spell Aron with a single “a.” Based on this, he wired $25,000 to Elvis. Richard eventually came to believe that he had been scammed.

Richard, seeking to recover the money lost, made a claim for coverage under his Crime policy with Bismark Mutual Insurance Company. The policy provided coverage as follows: “The Company will pay the Insured for the Insured’s direct loss of, or direct loss from damage to, Money, Securities and Other Property directly caused by Computer Fraud.” The policy defined “Computer Fraud” to mean: “The use of any computer to fraudulently cause a transfer of Money, Securities or Other Property from inside the Premises or Financial Institution Premises: 1. to a person (other than a Messenger) outside the Premises or Financial Institution Premises; or 2. to a place outside the Premises or Financial Institution Premises.”

Bismark Mutual disclaimed coverage, arguing that Billings could not prove that his loss had been caused by a fraudulent transfer of money. Bismark maintained that, because Billings had spent decades, and substantial money, in asserting that Elvis Presley was alive, he could not have believed that he had been fraudulently induced into sending money to the sender identified as “earonp.”

Richard filed suit against Bismark Mutual Insurance Company. In a recent decision in Billings v. Bismark Mutual Insurance Company, No. 18-2365 (Ward Cty. N.D. Apr. 9, 2017), the court found in favor of the insurer. The court held as follows:

“The content of plaintiff’s website demonstrates an individual as confident that Elvis Presley is alive as that the sun rises in the east. It was on this basis that plaintiff wired $25,000 to “earonp.” In return, Plaintiff was to receive knowledge that, for the rest of Elvis’s days, the legendary singer would have plaintiff’s kindness in his heart. Simply put, plaintiff, having spent so long believing that Elvis is alive, cannot prove that he was fraudulently induced to wire the money. Nothing from this transaction changes the mountain of evidence that plaintiff purports proves that Elvis is alive. Therefore, plaintiff cannot now change course, for the benefit of his claim, and maintain that the sender of the e-mail was not Elvis Aron Presley.” Billings at 4.

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Contest: Insurance Coverage New Year’s Resolutions

Win An Autographed Copy Of John Grisham’s Recently Released Book:

The Judge’s List

|

|

|

| |

|

|

What could be a more perfect contest for this issue: Insurance Coverage New Year’s Resolutions! It’s easy. Just send a new year’s resolution that someone who works in insurance coverage would make. Send as many entries as you’d like. Deadline to enter – January 14.

The winning entry will receive an autographed copy of John Grisham’s recently released book, The Judge’s List.

My resolution for 2022: I resolve to lose 10 pounds while drafting reservation of rights letters. |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

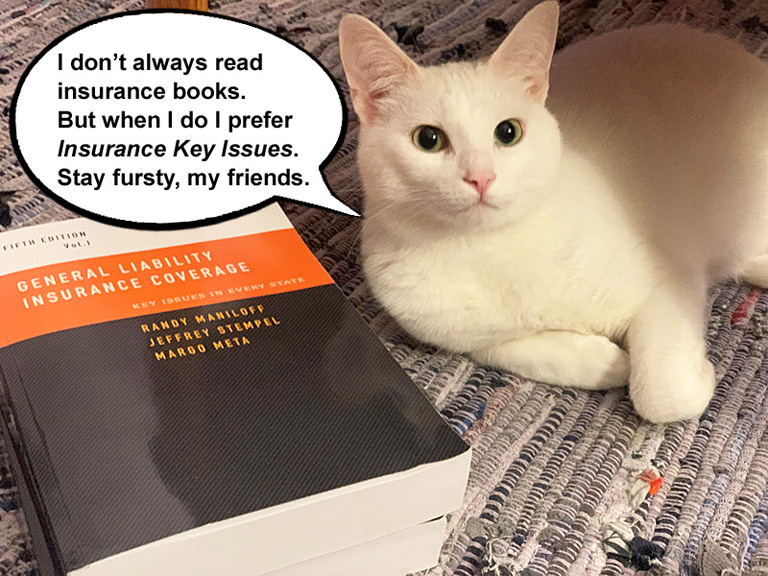

Legolas Is Back: The “Insurance Key Issues” Spokes-cat

|

|

|

| |

Close readers of Coverage Opinions will remember Legolas, introduced last March as the official spokes-cat for the 4th edition of Insurance Key Issues. Legolas, age two, belongs to Zurich’s Carrie Von Hoff.

It wasn’t easy, but the cat, named for the Lord of the Rings character, and I came to terms on a deal that would make the feline the official spokes-cat for the 5th edition ofKey Issues. The sticking point was number of years and brand of yarn he would get.

A resident of Evanston, Illinois, Legolas enjoys sleeping on heating vents, pouncing his brother Gimli, climbing into laundry baskets, and attacking house slippers to get to the insoles. His favorite toys include a tiny cat sized soccer ball, a mouse-shaped laser pointer, ribbons, and pretty much any toy with a feather. His favorite meal is canned chicken dinner with gravy. [Carrie doesn’t like to brag, but Legolas also sings a killer rendition of Memory.]

Despite being the official spokes-cat for the 5th edition ofKey Issues, Legolas says that he prefers the 4th edition. He says sorry, but he’s finicky. More about the 5th edition ofKey Issues here:

www.InsuranceKeyIssues.com

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2021

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Well, Francis Albert, maybe it was a very good year for city girls who lived up the stairs, with all that perfumed hair, but not so much for the world of liability insurance coverage. Quite simply, it was a very blah year. There wasn’t a single case in 2021 that really rocked the insurance coverage world.

That’s not to say that there weren’t many significant decisions handed down. Of course there were. There always are. And I was still able to find ten particularly significant ones (although, some gave me pause). Look, it happens. It’s just the way the chips fall. It’s too bad. I was hoping that the 21st annual Top 10 coverage cases article would have a little more of a champagne-like pop to it.

As always, there were a few cases that generated a fair amount of buzz, but, for various reasons, didn’t meet the strict Top 10 selection process.

The decision by the Illinois Supreme Court, in West Bend Mut. Ins. Co. v. Krishna Schaumburg Tan, Inc., that coverage is owed, under a commercial general liability policy, for violation of the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), was met with hyperventilation in some coverage circles over its significance. But its impact is limited to Illinois. As far as I know, BIPA-type statutes do not exist in other states. So Krishna Schaumburg, with no ability to have wide-spread influence, is not the kind of coverage decision that would be selected as one of the year’s ten most significant. My favorite part of the decision – BIPA is a fun word to say.

In Landry’s, Inc. v. Ins. Co. of the State of Pa., the Fifth Circuit held that coverage was owed under a commercial general liability policy, for losses sustained when an unauthorized program was installed on a restaurant’s payment processing devices that enabled card numbers and customer names and other important information to be taken. Since most businesses have a CGL policy and not a cyber policy, any decision that finds coverage for a data breach, under a CGL policy, is quite a big deal. However, the case involved a breach that occurred in 2014-2015 and the policies at issue did not include a data breach exclusion. Given how prevalent these exclusions have been in CGL policies over the past several years, Landry’s is unlikely to have much influence. BIPA

The two biggest insurance coverage stories of the year were, first, the hundreds of opinions addressing coverage for Covid-19 business interruption losses. The second was the ALI Liability Insurance Restatement, which had been quiet since its adoption in 2018, being cited by courts, several times, for substantive purposes. While the ALI Restatement did not dictate any decisions (except, maybe, Thompson v. Widmer Construction (D. Ore. 11/10/2021)), it was cited for substantive purposes in several, i.e., not simply to state a general principle of coverage law.

While the Covid-19 business interruption cases involve property policies, which are not the subject of this annual insurance coverage best-of, the story was just too significant to ignore here. Plus, many involved in liability coverage, and not normally property coverage, all of a sudden found themselves in the thick of Covid-19 business interruption cases. Many who have spent a career thinking that BI meant “bodily injury” were now using it to mean “business interruption.” So the story is relevant to CO readers.

As widely reported, state and federal courts issued hundreds of decisions – both at the trial and appellate level – addressing coverage for Covid-19 business interruption losses. It was a landslide win for insurers. According to Penn Law School’s latest numbers, insurers won 94% of cases before federal district courts and 72% at the state trial level. Insurers have also won every decision from federal circuit courts of appeal.

This is Reagan-Carter, the Globetrotters vs. Washington Generals, Tiger at the 1997 Masters [final round on my wedding day, fyi.]. Even Ted Lasso couldn’t find anything positive in this for policyholders. While the decisions numbered in the several hundreds, I make the case here that one is worthy of being called the most significant. As an aside, I addressed the state of Covid-19 business interruption coverage in a September 29, 2021 article in The Wall Street Journal. https://www.coverageopinions.info/WSJCovidRaid.pdf.

As I set out every year, the process to choose the ten most significant coverage cases works like this. It is a one-man show, devoid of input from others, accountability or checks and balances. Like all endeavors of this sort, the conclusions are highly subjective and in no way scientific. Debate and disagreement is inevitable. In fact, it is wat makes the exercise fun.

But none of this is to say that the selection process is willy-nilly. To the contrary, it is very deliberate and involves a lot of analysis, balancing, hand-wringing and tossing and turning at night. It’s just that only one person is doing any of this.

As for the selection process, it goes throughout the year to identify coverage decisions (usually, but not always, from state high courts) that (i) involve a frequently occurring claim scenario that has not been the subject of many, or clear-cut, decisions; (ii) alter a previously held view on an issue; (iii) are part of a new trend; (iv) involve a burgeoning or novel issue; or (v) provide a novel policy interpretation. Some of these criteria overlap. Admittedly, there is also an element of “I know one when I see one” in the process. In addition, cases that meet the selection criteria are usually (but not always) not included when the decision is appealed. In such situation, the ultimate significance of the case is up in the air.

In general, the most important consideration, for selecting a case as one of the year’s ten most significant, is its potential ability to influence other courts nationally. Many courts in coverage cases have no qualms about seeking guidance from case law outside their borders. In fact, it is routine--especially so when in-state guidance is lacking. The selection criteria operates to identify the ten cases most likely to be looked at by courts on a national scale and influence their decisions.

That being said, the most common reason why many unquestionably important decisions are not selected is because other states do not need guidance on the particular issue, or the decision is tied to something unique about the particular state. Therefore, a decision that may be hugely important for its own state – indeed, it may even be themost important coverage decision of the year for that state – nonetheless will be passed over, as one of the year’s ten most significant, if it has little chance of being called upon by other states at a later time. Similarly, some decisions are not selected because they involve narrow issues that rarely arise.

For example, consider a state high court that issues its first decision addressing the scope of the pollution exclusion. The case answers whether the pollution exclusion should be interpreted broadly, applying to all hazardous substances, or narrowly, applying solely to so-called traditional environmental pollution. This would be a very significant decision for that state. However, given the enormous body of case law nationally, addressing the pollution exclusion, such a decision would be very unlikely to have any influence nationally. It would be just one decision in an ocean of many on the issue. Thus, the decision would not be selected for inclusion here.

If you think I missed a case, tell me. I’ll be the first to admit that I goofed (and I have). It is impossible to be aware of every coverage case decided nationally.

The ten most significant insurance coverage decisions are listed in the order that they were decided.

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

D&O Insurer Need Not Submerge Its Own Interests In Withholding Consent To A Settlement

Apollo Education Group, Inc. v. National Union Fire Ins. Co., 480 P.3d 1225 (Ariz. 2021)

|

|

|

| |

At issue before the Arizona Supreme Court, in Apollo Education Group, Inc. v. National Union, is how an insurer must respond to an opportunity to settle an underlying action, under a no duty to defend policy that affords the insurer the right to consent to a settlement, provided that it is not unreasonably withheld.

The policy at issue was directors and officers liability and did not contain a defense obligation. Admittedly, this is quite different from a commercial general liability policy -- that almost always contains a duty to defend. And, of course, claims and settlements are far, far and away more common under CGL policies, which gives rise to a different analysis. Nonetheless, I chose Apollo Education Group, for inclusion here, because of the significant deference that the court gave to the insurer in its decision to withhold consent to settle.

One of policyholders’ most common arguments, when it comes to insurers’ handling of claims, is that the insurer must not put its own interests ahead of the insured’s. The refrain sometimes goes so far as an insurer must even submerge its own interests to that of the insured’s. But that simply was not the result here. Not even close. Even with a D&O policy, since Apollo goes so strongly against this oft-asserted purported principle -- as well as the decision providing guidance by way of a lengthy list of factors whether an insurer’s decision, not to consent to a settlement, was reasonable -- I chose it for inclusion here.

Apollo Education Group suffered a significant drop in its stock price after the SEC accused it of backdating stock options awarded to executives. A class action was filed against Apollo. National Union refused to consent to a settlement. Apollo settled on its own for $13,125,000 and sought coverage from National Union under a D&O policy.

The Supreme Court of Arizona answered the following re-stated certified question from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals: “Should the federal district court assess the objective reasonableness of National Union’s decision to withhold consent from the perspective of an insurer or an insured?”

The relevant policy provision, concerning an insurer’s consent to settle, stated: “The Insureds shall not admit or assume any liability, enter into any settlement agreement, stipulate to any judgment, or incur any Defense Costs without the prior written consent of the Insurer. Only those settlements, stipulated judgments and Defense Costs which have been consented to by the Insurer shall be recoverable as Loss under the terms of this policy. The Insurer’s consent shall not be unreasonably withheld, provided that the Insurer shall be entitled to effectively associate in the defense, the prosecution and the negotiation of any settlement of any Claim that involves or appears reasonably likely to involve the Insurer.” (emphasis added).

First, the court concluded, following some analysis of the issue, but, ultimately, with not a lot of trouble, that the reasonableness of withholding consent to a settlement is to be viewed from the insurer’s perspective.

The court next turned to the heart of its decision – the factors that determine if the insurer’s decision, to withhold consent to settle, was reasonable. After concluding that the inquiry is an objective one – the way a reasonable insurer would be expected to act – the court held as follows:

[The court’s explanation, of what the insurer must do, to act reasonably, is lengthy. I set it out here, in full, as it necessary to see it all to appreciate the significance of the decision]

“To act reasonably, the insurer is obligated to conduct a full investigation into the claim. The Court has described the insurer’s role as an almost adjudicatory responsibility. To carry out this responsibility, the insurer evaluates the claim, determines whether it falls within the coverage provided, assesses its monetary value, decides on its validity and passes on payment. The company may not refuse to pay the settlement simply because the settlement amount is at or near the policy limits. Rather, the insurer must fairly value the claim. The insurer may, however, discount considerations that matter only or mainly to the insured—for example, the insured’s financial status, public image, and policy limits—in entering into settlement negotiations. The insurer may also choose not to consent to the settlement if it exceeds the insurer’s reasonable determination of the value of the claim, including the merits of plaintiff’s theory of liability, defenses to the claim, and any comparative fault. In turn, the court should sustain the insurer’s determination if, under the totality of the circumstances, it protects the insured’s benefit of the bargain, so that the insurer is not refusing, without justification, to pay a valid claim.”

Of note, the court stated that considerations of coverage are in play for the insurer’s decision, as well as the insurer having the right to “discount considerations that matter only or mainly to the insured,” such as its insured’s financial status, public image and policy limits. The insurer can also base its decision on simply a reasonable determination of the value of the claim and potential liability. The court also noted that the insurer “need not consider any additional factors that may have induced the insured to settle.”

Clearly, the insurer has a significant place at the settlement table and it certainly need not abandon or dramatically minimize its own interests, as many policyholders would maintain.

The dissent had much to say about the deference given to an insurer faced with a demand to consent to a settlement: “[B]ecause there is no standard set forth in the policy itself, based on the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing, National was required to give equal consideration to the interests of Apollo in deciding whether to consent to the settlement agreement. Arizona has spent several decades carefully developing the equal consideration standard to protect insureds from the potential financial ruin they face in third-party claims. Unfortunately, today, the majority has decided to depart from that jurisprudence. This will undoubtedly create confusion and generate litigation for years to come.”

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Choice Of Law Whopper For D&O Coverage Disputes

RSUI Indemnity Company v. Murdock, 248 A.3d 887 (Del. 2021)

|

|

|

| |

On its face, the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision, in RSUI Indemnity Company v. Murdock, seems an odd choice for inclusion as one of the year’s ten most significant involving coverage. At issue was the First State’s test for determining what state’s law applies to adjudicating coverage under a director’s and officer’s liability insurance policy. With choice of law being such a well-developed issue nationally, Murdock seems the classic situation of a case, while very important for its own jurisdiction, that is not going to influence decisions across the country. This is a significant reason why seemingly important decisions are not included on this annual insurance coverage hit parade.

Despite this, Murdock had no problem landing a spot. While the decision is unlikely to affect how other states address choice of law for D&O disputes, it can still be expected to have a national footprint, namely, affecting where some of these coverage suits are filed.

At issue in Murdock was coverage for claims that two of Dole Food’s officers manipulated the price of Dole’s stock, making it artificially low, to enable the company to be taken private for a reduced amount.

Dole’s shareholders filed suit. Following a nine-day trial, the Delaware Chancery Court found that the officers engaged in fraud and certain intentionally misleading conduct and were liable for nearly $150 million in damages. The judgment was paid in full. Dole then settled a related case for $74 million.

As you can imagine, with these kinds of numbers, there were numerous insurers involved and claims asserted. A coverage action was filed by certain insurers, followed by insurers making payments or reaching settlements. To keep it simple here, what matters is that one insurer, RSUI, did not settle. The court entered judgment against RSUI for its policy limits of $10 million plus $2.3 million in prejudgment interest.

Two of RSUI’s principal defenses were that coverage was precluded under California law [Insurance Code section 533’s preclusion of coverage for willful acts] as well as the policy’s Fraud/Profit exclusion.

As RSUI saw it, California law controlled, as many of the contacts to the coverage dispute were tied to California. These included such important factors as the policy being negotiated and issued in California, where Dole was headquartered, as well as the policy containing California amendatory endorsements. The insureds’ countered that Delaware law applied as Dole was incorporated in Delaware.

The supreme court undertook an analysis of choice of law under the Restatement (Second) Conflict of Laws’ “most significant relationship test.” While there are numerous factors that go into the Restatement’s most significant relationship test – it can be a bear to analyze -- when all is said and done, it usually points to the state where the policy was issued as the one whose law controls.

Based on this, it should have been an easy decision for the court to conclude that California law applied. California’s several connections to the policy dominated over the single Delaware contact -- Dole’s state of incorporation.

But the court concluded that Delaware law applied: “Nor do we find the other previously discussed California contacts to be as legally significant or as laden with policy considerations as Dole’s status as a Delaware corporation and the individual insureds’ status as directors and officers, all operating under the authority and guidance of Delaware law. To be clear, we do not ignore the California contacts and acknowledge that they might be dispositive were we addressing an insurance policy covering a different subject matter and insureds with a more tenuous connection to Delaware than a Delaware corporation and its directors and officers have. Yet when we balance the California contacts against Delaware’s interest in protecting the ability of its considerable corporate citizenry to secure D&O insurance and thereby attract talented directors and officers, and for the other reasons mentioned above, we find that Delaware has the most significant relationship to the Policy and the parties.”

Having concluded that Delaware law applied, RSUI lost the ability to argue that California Insurance Code section 533 precluded coverage.

But what about the insurer’s fallback argument: Delaware public policy precludes coverage for intentional and fraudulent wrongdoing. For various reasons, not discussed here, the court held that public policy was not a bar to coverage: “The question here then is: does our State have a public policy against the insurability of losses occasioned by fraud so strong as to vitiate the parties’ freedom of contract? We hold that it does not. To the contrary, when the Delaware General Assembly enacted Section 145 authorizing corporations to afford their directors and officers broad indemnification and advancement rights and to purchase D&O insurance ‘against any liability’ asserted against their directors and officers ‘whether or not the corporation would have the power to indemnify such person against such liability under this section,’ it expressed the opposite of the policy RSUI asks us to adopt.”

The court also held that the policy’s Profit/Fraud exclusion did not apply, as the requirement of fraudulent acts being established by a final and non-appealable adjudication, adverse to the insured, had not been satisfied [there was a technical analysis to arrive at this].

The take-away from Murdock is easy to see. A Delaware-incorporated insured – which is a popular place of incorporation for the types of companies involved in significant D&O matters -- seeking coverage under a D&O policy, can file a coverage action in Delaware and secure application of Delaware law. Translation -- get the benefit of the state’s principle that fraudulent conduct is insurable, even if the insured has no other connection to Delaware. Welcome to the race to the courthouse, with insurers seeking to file coverage actions in a state that would not apply Delaware law – which is presumably most states, if the insured’s only connection to Delaware is that the insured is incorporated there.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Bad Faith Failure To Settle -- But No Demand Within Limits, No Trial, No Excess Verdict And Insured Fully Released

Planet Bingo LLC v. Burlington Insurance Co., 62 Cal. App. 5th (2021)

|

|

|

| |

Top 10 cases can be ones that go against conventional thinking about an issue. The California Court of Appeal’s decision in Planet Bingo LLC v. Burlington Insurance Co. is a classic in that category. In other words, the decision has a surprise element.

The court determined that the insurer could be liable for bad faith failure to settle. However, here’s the rub – a settlement demand, within policy limits, was never made. And here’s the second rub – there was no excess verdict. And that’s because of the third rub – the underlying case against the insured never actually went to trial. Wait, there’s one more – the insurer secured a full release for its insured. Needless to say, these are certainly not the usual ingredients for an insurer to possibly be liable for bad faith failure to settle. Hence, the decision is discussed here.

I’ll give away the ending. The court concluded that, when a settlement demand is for a subrogation claim, even if it is above policy limits, it could be deemed to be a demand for policy limits. This is because the court was persuaded that it is a very well-known industry custom, in subrogation claims, of accepting policy limits for a full release of the insured.

Second, the court found support for its subrogation-claim decision on the basis that, under California law, an insurer’s refusal, to simply disclose what its policy limits are, can be considered its refusal of an actual settlement demand made for policy limits.

All in all, the decision can likely be relevant to non-subrogation claims as well.

Insurers usually find protection, for bad faith failure to settle, on the basis that there was never a demand to settle within limits made. In other words, the opportunity to settle was never there. Based on Planet Bingo, the analysis is not just mathematical, t also situational.

Planet Bingo involves a protracted history and the facts are a little confusing. I’m going to stick to those that mattered the most to the court’s decision. At issue in Planet Bingo was coverage for a fire, in September 2008 in the United Kingdom, caused by an electronic gaming device designed and supplied by Planet Bingo. Leisure Electronics was the distributor of the devices. The fire took place at Beacon Bingo, a bingo hall in London. Plant Bingo sought coverage from its liability insurer, Burlington. The policy limit was $1 million.

In November 2009, Beacon Bingo notified Burlington that its damages totaled £1.6 million – about $2.6 million. In mid-2011, while neither Beacon nor Leisure had filed suit against Planet Bingo, the company advised Burlington that it was losing business because the fire claim remained unpaid and Plant Bingo “was getting known as a deadbeat.” Around that time, Burlington advised Planet Bingo that, since no claims were being pursued against it, the insurer was closing its file.

Meanwhile, AIG Europe Ltd., the insurer for Leisure, the distributor, settled with Beacon, the bingo hall, for £1.6 million. In July 2014, AIG contacted Planet Bingo, advised of the Leisure settlement, and made a subrogation demand of £1.6 million. AIG also stated that it was open to alternative dispute resolution. [I’ll get to the importance of the subro issue soon).

Planet Bingo notified Burlington of the claim. Burlington denied coverage on the basis that, as required by the policy, the fire did not occur in the United States or Canada and Planet Bingo had not been sued in the United States or Canada.

Planet Bingo’s attorneys convinced AIG it to sue Planet Bingo in the United States. AIG did so in California Superior Court. Burlington accepted the defense, subject to a reservation of rights, and settled with AIG for $1 million — the policy limits. AIG released any and all claims against Planet Bingo.

So case over, right? Sure, it took a long time to get there, but all’s well that ends well. Uh, no.

Planet Bingo had filed a coverage action against Burlington in 2016. Planet Bingo’s expert witness testified that “the failure to promptly pay the fire claim damaged Planet Bingo’s business reputation and ultimately caused its entire business in the United Kingdom to fail; as a result, it suffered lost profits of over $9.3 million. Burlington did not dispute this.” (emphasis mine).

The trial court ruled that Burlington was not liable for pre-litigation failure to settle. But the Court of Appeal reversed.

The appeals court, while noting that this was not a “paradigm case” of bad faith failure to settle – demand to settle within limits; insurer rejects it; case goes to trial; excess verdict – the insurer could be liable for pre-litigation failure to settle.

In making this determination, the court noted that, on its face, there was never a demand within limits on the table. AIG Europe demanded £1.6 million and Planet Bingo’s policy had a $1 million limit. And there was never an excess judgment. While AIG did have to sue Planet Bingo, Burlington settled for policy limits. However, Planet Bingo’s argument was that, by Burlington not settling pre-suit, its business in the UK was wiped out.

The court concluded that there may have been a demand to settle within limits. Wait, where? Well, that’s the surprising part. AIG’s £1.6 million demand was a subrogation demand. The court observed that, because it was a subrogation demand, it could have been considered a demand for limits.

The court explained: “It is significant that AIG was claiming as subrogee, and its letter was a subrogation demand letter. Planet Bingo’s expert witness testified that a subrogation demand letter ‘offers a clear invitation to negotiate a settlement for less than that amount . . . .’ She also testified that there is a ‘very well[-]known industry custom in such subrogation claims of accepting policy limits for a full release o[f] the insured.’ This raised a triable issue of fact as to whether the letter represented an opportunity to settle within the policy limits.”

Second, in reaching the conclusion, that a settlement demand can be a demand within limits, even if the demand is higher than the limits, the court was persuaded by Boicourt v. Amex Assurance Co., 78 Cal. App. 4th 1390 (2000), where an insurer’s pre-litigation refusal, to simply disclose what its policy limits are, could be considered its refusal of an actual settlement demand made for policy limits. The Planet Bingo court stated that, in Boicourt, the claimant, after getting an excess verdict, testified that he would have accepted policy limits if he knew what they were.

Planet Bingo isn’t over. It was a denial of summary judgment on the failure to settle issue. In addition, the court needs to decide whether Planet Bingo can recover lost profits rather than an excess judgment.

However, the take-away from Planet Bingo is clear. The court stated: “At a minimum, Boicourt [and now, seemingly, Planet Bingo] means that the existence of an opportunity to settle within the policy limits can be shown by evidence other than a formal settlement offer.”

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Excess Policy Allocation Between Covered And Uncovered Claims

RSUI Indemnity Company v. New Horizon Kids Quest Inc., 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 63424 (D. Minn. April 1, 2021)

|

|

|

| |

This a first in my two-decades of identifying the Top 10 coverage cases of the year – an encore.

The 2019 Top 10 cases article included the Eighth Circuit’s decision in RSUI Indemnity Co. v. New Horizon Kids Quest, Inc. There, the federal appeals court remanded to the Minnesota District Court. The Minnesota court issued its opinion in 2021. And that decision is also worthy of inclusion at one of the ten most significant of the year.

The issue – one that I have long discussed in Coverage Opinions and with clients – is the need for insurers to address, pre-trial, allocation between covered and uncovered damages. There are many good reasons for doing so. But, for various reasons, it doesn’t always happen. Perhaps the insurer did not take any steps. Or, maybe it did, and the court said no-go. Either way, as a result, the verdict that comes down against the insured is unallocated. In other words, it’s just one number and does not include an explanation of the nature of the damages that it represents, despite that it could represent more than one type – and some of which are covered and some not.

When this happens, the insurer will likely be disinclined to pay damages that include some, or maybe a lot, that are uncovered. The insured, however, will likely seek coverage for the entirety of this “general verdict,” despite the possibility (sometimes strong possibility) that it includes uncovered damages. The insured will likely maintain that this is the consequence to be borne by the insurer since it did not take pre-trial steps to achieve an allocation. Or, at least the insurer has the burden to prove which damages are uncovered. Despite the importance of this issue, it wants for case law.

This is the issue in RSUI Indemnity Co. v. New Horizon Kids Quest, Inc. Since the 2021 decision is a follow-on to the 2019 decision, I’ll start with the Eight Circuit’s earlier decision.

I am going to quote liberally from the Eighth Circuit’s New Horizon opinion. New Horizon Kids Quest, Inc. operates a childcare facility at the Grand Casino Mille Lacs in Onamia, Minnesota. New Horizon was sued for negligent supervision and training on account of J.K., then age three, suffering physical and sexual assaults at the hands of N.B., then age nine.

Travelers provided New Horizon with $3,000,000 of liability coverage and RSUI provided excess liability coverage of up to $8,000,000 per occurrence. This is important – the RSUI policy included a Sexual Abuse or Molestation Exclusion.

Travelers defended New Horizon in J.K.’s suit. “Following a second trial [motion for new trial was granted after a $13 million award] at which New Horizon again conceded liability but contested J.K.’s claims of injuries and damages, the jury awarded total damages of $6,032,585, segregating its award into four damage categories but not finding whether J.K. suffered sexual as well as physical abuse and not allocating its award between those two claims. Travelers paid its policy limits, plus interest. New Horizon paid the remaining $3,224,888.59 and demanded indemnity from RSUI under its excess liability policy. RSUI then brought this action seeking a declaratory judgment that the policy’s ‘Sexual Abuse or Molestation’ exclusion barred coverage for that part of the award above Travelers’ policy limits.”

“The district court granted New Horizon summary judgment because, without an allocated award or jury interrogatory, RSUI is unable to prove ‘that the jury determined sexual abuse had occurred or that one cent of the award was based on such a determination.’”

RSUI appealed and the Eight Circuit reversed: “We conclude that RSUI, an excess liability insurer that did not control the defense of its insured in the underlying suit, must be afforded an opportunity to prove in a subsequent coverage action that the jury award included damages for uncovered as well as covered claims. If the insurer sustains that burden, the district court must then allocate the award between covered and uncovered claims.”

While the court concluded that RSUI had the burden to prove that the jury award included an uncovered sexual assault claim, there is also the critical issue of which party would then have the burden to allocate the unallocated jury award. The Eight Circuit (happy to do so, it seemed) handed that issue back to the District Court.

** This is where the 2021 case picks up. First, and not the critical part for the decision for discussion here, the Minnesota District Court held that it was clear that some portion of the jury award was based on violative conduct of a sexual nature, i.e., the sexual abuse exclusion applied, as well as conduct of a physical assault. Thus, RSUI won this portion of the case, namely, proving that some aspect of the damages involved an excluded claim.

But the insurer lost on the next issue – who had the burden to prove, at a jury trial, which portion of the damages were for excluded sexual abuse and which were for the covered conduct, i.e., a physical assault. The court concluded that this burden of proof, even with RSUI being an excess insurer, fell on the insurer. The court’s reasoning, with much reliance on a 2012 Minnesota Supreme Court decision, was, in part, as follows:

“RSUI had a duty to notify New Horizon of its interest in a written explanation of the damages award. First, RSUI had a duty of good faith toward New Horizon, as RSUI uniquely knew the scope of the policy’s coverage and exclusion, and intended to exercise the Exclusion despite only issuing a tentative reservation of rights. Additionally, RSUI’s participation in New Horizon’s defense without disclosing its intent to exercise the Exclusion creates the possibility of prejudice to New Horizon, such as if RSUI had attempted to steer the litigation in a direction that would make it easier to later disclaim coverage. The duty to notify is intended to eliminate such opportunities for prejudice to the insured.

“Second, it would not have been onerous for RSUI to notify New Horizon of its interest in a written explanation. New Horizon informed RSUI of the underlying lawsuit more than three years before the verdict in the second trial, RSUI was present for and assisted with portions of the defense, and RSUI provided New Horizon with a reservation of rights letter several months before the second trial. RSUI had ample opportunity to notify New Horizon of its interest in a written explanation of the verdict, and it would not have been onerous to do so. Therefore, the first condition is established.

“Next, the insured must affirmatively show ‘that a written explanation of an award is available under the applicable rules.’ The Minnesota Rules of Civil Procedure allow for special verdicts and jury interrogatories which, if requested, would have allowed for a written explanation of the jury’s award to facilitate allocation. See Minn. R. Civ. P. 49. The second condition is met.”

Given that the court provided so many factors why the allocation burden should be placed on the insurer, the decision may be a go-to for other courts confronting the issue. It remains to be seen whether this allocation burden can be satisfied by the insurer. In addition, while the insurer has this burden, some courts do not even allow an insurer, that fails to take action to achieve an allocated verdict, to even try it. In other words, some courts simply conclude that, if the insurer failed to take action to achieve an allocated verdict, the entirety of the verdict is covered.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

The Sticky Wicket: Handling A Settlement With Uncovered Claims

In Re Farmers Texas County Mut. Ins. Co., 621 S.W.3d 261 (Tex. 2021)

|

|

|

| |

There is no doubt that, when it comes to important courts for insurance coverage, the Texas Supreme Court is near, or even at, the top. [In a years-ago issue of CO I undertook a detailed study of why I believe this to be the case.] So, when the Texas Supreme Court handed down its decision in In re Farmers Texas County Mut. Ins. Co. I of course took close note. Now, throw in that the case involves one of the most challenging coverage issues of them all – an insurer facing an opportunity to settle, but has a coverage defense -- and it was like a hot knife through butter to choose it for inclusion here. For more about this issue, and its challenges, see the discussion of Owners Ins. Co. v. Dockstader below.

At issue in Farmers Texas was an insurer with an opportunity to settle a claim within limits -- but it had a coverage defense that made it less inclined to do so. To be clear, while the solution provided by the Texas high court may have fit the facts at issue, it is one that is not likely to work in many situations. However, coming from Austin, and with any guidance on the issue valuable, it was deserving to be include here.

Farmers Texas involves coverage for an automobile accident. Cassandra Longoria rear-ended a vehicle being driven by Gary Gibson. Gibson sued Longoria. She was insured under a policy issued by Farmers Texas County Mutual Insurance Company, which undertook her defense.

Gibson sought damages of $1 million. Longoria’s policy had a $500,000 limit. As trial approached, Gibson agreed to settle for $350,000. Farmers refused to contribute more than $250,000. As Farmers saw it, there was a coverage defense – Longoria had acted grossly negligent -- which justified it paying less than the full demand. Longoria, concerned about her personal exposure, offered to pay the additional $100,000, but without waiving her right to seek recovery of that payment from Farmers. Gibson accepted and gave Longoria a release in exchange for Farmers’ and Longoria’s payments.

Longoria sued Farmers, alleging all manner of claims, and sought recovery of her $100,000 payment. The Texas Supreme Court concluded that Longorio had a right to recovery. She still needed to do more to win, but the right existed. [The court also addressed, and rejected, that a cause of action existed for negligent failure to settle, i.e., Stowers, as there was no liability in excess of policy limits.]

In reaching its decision, the court cited to its well-known decisions in Frank’s Casing and Matagorda, which hold that “[i]f a liability insurer disputes whether some claims asserted against its insured are covered, it may comply with its policy obligations by defending under a reservation of rights, and it may settle the entire suit and—with the insured’s consent—reserve for separate litigation the question whether the insured should reimburse it for part of the settlement.”

The Texas Supreme Court concluded that the matter at hand was reverse Frank’s Casing and Matagorda: “This approach also works the other way: if an insurer agrees to settle some claims but refuses to cover others, the insured may join with it to settle the entire suit and reserve for separate litigation the question whether the insurer should reimburse it for the remainder of the settlement.”

As the court saw it, Farmers Texas’s right to settle, as it considers appropriate, was separate from Longoria’s ability to assert a claim that Farmers breached a separate promise to pay damages for which the settlement made her legally responsible.

In essence, under the rule announced in Farmers Texas, the insured can take action to protect itself against an excess verdict and personal liability and save for afterwards to prove that the insurer failed to provide coverage. While the solution worked here, because Longoria was able to make a $100,000 contribution to the settlement, it will surely not be the cases in many other instances.

The court, seemingly recognizing that other cases will involve insureds that settled with no insurer participation, provided guidance for such scenario. Even if it is determined that coverage is owed, “[a]n insurer also will not be obligated to indemnify its insured for a settlement that is collusive or unreasonable in amount.”

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Injunctive Relief Is Covered “Damages”

Sapienza v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Company, 960 N.W.2d 829 (S.D. 2021)

|

|

|

| |

There are certain factors that make an insurer-loss potentially significant. These include a decision that (1) involves an issue with potentially broad applicability and frequency, i.e., it is not tied to a narrow set of facts and it can arise under various types of liability policies; (2) goes against a generally accepted insurer position on an issue; and (3) comes from a state high court.

The South Dakota Supreme Court’s decision, in Sapienza v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Company, has all of these, making it an easy decision to include here. The court held that coverage was owed to an insured, under a liability policy, for its cost to comply with an injunction. The court held that such costs qualified as covered “damages.”

In my experience, and yours too I’m sure, insurers generally do not treat an insured’s obligation, to comply with an injunction, as covered “damages.” While I believe that Sapienza was wrongly decided – as did two of the five justices – the decision provides an opportunity for policyholders to make the argument, that was successful before the South Dakota high court, to secure coverage for injunctive relief.

Sapienza involved a battle royale between neighbors. The Sapienzas obtained a building permit to raze their existing home and build a new one. The McDowells lived next door, in a home listed on the state and national register of historic places. You know where this is going.

After the Sapienzas home was completed, the McDowells filed suit, alleging illegalities in its construction and problems that it caused for the McDowells:

- Only seven feet of space between their home and the Sapienzas’ home, which violated applicable administrative regulations governing height, mass, and scale;

- McDowells prohibited from using their fireplace because of the close proximity and height of the Sapienzas’ home.

- Sapienzas’ home detrimentally affected the historic and sentimental value of their home, blocked a substantial amount of natural sunlight from the south, and invaded the privacy of their home by having windows that overlook the McDowells’ windows (including the window into the bathroom and bedroom of their daughter)

The McDowells’ complaint sought, in addition to injunctive relief, “compensatory, general, special, consequential and punitive damages in an amount to be determined to compensate [the McDowells] for all injuries sustained as a result of the conduct of [the Sapienzas.]”

The Sapienzas’ homeowner’s insurer, Liberty Mutual, undertook their defense. A bench trial was held and the court granted the McDowells a permanent injunction. The Sapienzas were ordered to either bring their residence into compliance with the applicable regulations or rebuild it.

The Sapienzas appealed – Liberty Mutual continued to defend – and the South Dakota Supreme Court affirmed. The case went back to the Sioux Falls Board of Historic Preservation to cure and remedy the violations. It did not get worked out and the Sapienzas had their home demolished and allegedly incurred $60,000 in complying with the permanent injunction.

Liberty Mutual denied coverage for these costs and the Sapienzas filed suit against Liberty in federal court. The insurer argued that the insuring agreement, of the liability potion of the policy, had not been satisfied, on the basis that the Sapienzas were not legally obligated to pay “damages.” In other words, as the insurer saw it, there were no damages awarded to the McDowells, but, rather, the Sapienzas were ordered to modify or tear down their own home.

The federal court certified the following question to the South Dakota Supreme Court: “Do the costs incurred by the Sapienzas to comply with the injunction constitute covered ‘damages’ under the Policies such that Liberty Mutual must indemnify the Sapienzas for these costs?”

The competing positions went like this. The Sapienzas argued the term “damages” is unambiguous and “encompasses both money paid to compensate for harm as well as any expenses, costs, charges, or loss incurred to remedy a harm.” They argued that “damages” includes “any economic outlay compelled by law to rectify or mitigate damage caused by the insured’s acts or omissions.” Of course, the Sapienzas also argued that the term “damages” is ambiguous if it has more than one meaning.

Liberty argued that “the nature of liability insurance contemplates an obligation to pay the damages to another party for which the insured is legally liable. . . .[B]ecause there were no damages awarded to the McDowells and the court instead required the Sapienzas to modify or tear down their own home, the Sapienzas did not become legally liable for damages to the McDowells because of property damage.”

The high court sided with the Sapienzas for various reasons – principally based on a dictionary definition of damages: “[A]pplying the definition of ‘damages’ that includes not only reparation in money as a form of compensation, but also a ‘satisfaction imposed by law for a wrong or injury caused by a violation of a legal right,’ the costs the Sapienzas incurred to comply with the injunction are covered ‘damages’ under Liberty Mutual’s policies. The Sapienzas paid these costs to ‘satisfy the wrong or injury’ they caused to the McDowells’ property—an injury for which they were ultimately held legally liable.” The court described “damages” as “costs predicated on [the Sapienzas] legal liability for what would otherwise be assessed as money damages had the court determined that a monetary payment to the McDowells would have been adequate to remedy the harm.”

Of note, the court did make an important point that insurers will likely cite in response to arguments for coverage: “[I]t is important to recognize that the nature of the injunctive relief governs whether sums paid for such would be covered under policy provisions of the sort here. Not all injunctions have the same purpose. . . . [C]osts associated with injunctive relief ordered to prevent property damage that has yet to occur “are not ‘damages because of property damage’” and, as a result, may not fall within coverage provisions.”

Two dissenting justices -- after criticizing the majority for being too quick to find ambiguity, just because of multiple dictionary definitions of an undefined term – saw the issue this way: “[W]e now know that the Sapienzas complied with the injunction by razing their house which, in turn, had the effect of removing the impediment to the McDowells’ fireplace and allowed more sunlight back into their home. But that result was not required or assured by the circuit court’s mandatory injunction, which directed only compliance with regulations governing construction in historic districts and was not specifically crafted to remedy the McDowells’ property damage claims. The plain fact that the McDowells’ concerns were ultimately alleviated does not mean that the Sapienzas were ordered to remedy the McDowells’ property damage claims relating to the lost use of their fireplace and diminished sunlight.”

The dissent also observed that the decision turned the liability policy into a first-party policy: “[A]applying the rule the Sapienzas and the Court suggest alters the Liberty Mutual liability insurance agreements, straining the text of the policies well beyond their limits and effectively converting the liability provisions into something more akin to first-party insurance by requiring ostensible liability coverage for property owned by the insured.”

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Insurer Can Sue Its Retained Defense Counsel For Malpractice

Arch Ins. Co. v. Kubicki Draper, LLP, 318 So. 3d 1249 (Fla. 2021)

|

|

|

| |

I went back and forth on whether to include the Florida Supreme Court’s decision, in Arch Ins. Co. v. Kubicki Draper, LLP, as a Top 10 coverage case of 2021.

The court held that an insurer can maintain a malpractice action against defense counsel that it retained to represent an insured. It is not at all a coverage case. However, the issue is relevant to many readers of this annual review. In addition, the case has across the board applicability, as insurers retain defense counsel for many kinds of liability policies and regardless of the facts at issue.

Also tipping the scales, while the issue is not devoid of case law nationally by any means, there is very little at the state supreme court level. Kubicki Draper follows on the heels of the South Carolina Supreme Court’s 2019 decision, in Sentry Select Ins. Co. v. Maybank Law Firm, LLC, which reached the same conclusion (but without addressing its theory). Thus, such recent decisions provide solid persuasive authority that the many jurisdictions, that have not addressed the issue, may look to and allow an insurer to maintain a malpractice action.

The decision is not lengthy nor complicated. Spear Safer, an accounting firm, was sued for malpractice by the receiver for a client that became subject to an SEC investigation. A settlement was reached with the SEC. Spear Safer was insured under a professional liability policy issued by Arch. Arch retained Kubicki Draper to defend Spear Safer in the malpractice action. Just before trial, the malpractice action against Spear Safer was settled for $3.5 million. Arch then filed suit against Kubicki Draper, alleging that the case against Spear Safer should have been barred by the statute of limitations, but the law firm failed to raise it. This, Arch maintained, significantly increased the settlement cost. At issue before the Florida high court was whether Arch could maintain a malpractice action against Kubicki Draper, the law firm that it hired to represent its insured.

The Florida high court held that, while the insurer was not in privity with the defense counsel (the insured was, as the client), the insurer could pursue a claim against the lawyer using a subrogation angle: “[C]onsistent with established principles of subrogation, because the insured is in privity with the law firm, contractual subrogation allows the insurer to step into the shoes of the insured. . . . Accordingly, contrary to the opinion’s conclusion below, Arch would have standing to pursue a legal malpractice claim against Kubicki.”

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Demand To Settle – But Insurer Has A Strong Coverage Defense

Owner’s Insurance Co. v. Dockstader, 861 Fed. Appx. 210 (10th Circuit 2021)

|

|

|

| |

For years, I have been calling this one of the most challenging of all coverage issues. An insurer is defending an insured under a reservation of rights. A demand is made to settle within limits. Based on the insured’s potential liability and plaintiff’s damages, and considering the applicable state standard for whether a claim should be settled, to avoid an insurer’s potential liability for an excess verdict, this one should be.

But here’s the rub. As I said, the insured is being defended under a reservation of rights. If the insurer settles, it could lose the ability to assert the coverage defense. If it declines to settle, because it does not wish to settle an uncovered claim, and the case goes to trial, and there is an excess verdict, the insurer could be liable for the excess verdict. And, if the insurer files a declaratory judgment action, it often-times won’t get an answer before the trial in the underlying action.

In other words, a demand is made to settle. Even though the insurer has a coverage defense, the result may be, at best, the insurer’s coverage defense is lost. At worst, the insurer is liable for an excess verdict.

Despite it being such a significant, confounding, frequently occurring and challenging issue, there is not a significant amount of case law addressing the impact of a coverage defense on an insurer’s obligation to settle and possible liability for an excess verdict. There is some, but there could be more.

The Tenth Circuit addressed this issue in Owner’s Insurance Co. v. Dockstader. It was not a paradigm excess verdict situation. But, given the importance of the issue, and limited case law, the court’s decision is worthy of being called one of the ten most significant coverage cases of the year.

The coverage issue at the heart of Dockstader is about as simple as it gets. Jacob Dockstader hit Thomas Brooks in the head with a dumbbell at a gym. Brooks was left permanently disabled. Dockstader pleaded guilty to aggravated assault.

Brooks sued Dockstader for assault and battery and negligence. Owner’s Insurance undertook Dockstader’s defense, under a homeowner’s policy issued to his parents, and did so under a reservation of rights. The policy limit was $500,000.

Not surprisingly, Owner’s Insurance asserted defenses based on no “occurrence” and an “expected or intended” exclusion. Owner’s filed a declaratory judgment action seeking a determination that it had no duty to defend or indemnify Dockstader for these reasons.

Brooks made three settlement demands for the policy’s $500,000 limit. He noted that his actual damages far exceeded the policy limit. In the court’s words, Owners “conditionally accepted” Brooks’ offer. “It referenced the declaratory judgment action and said, ‘[i]f there is coverage, [Owners] will pay the policy limit of $500,000 to Mr. Brooks.’”

Shortly after the third settlement offer, Owner’s filed a motion for summary judgment in the coverage action. While that was pending, and without notice to Owner’s, Dockstader and Brooks reached a settlement for $5,000,000. Brooks agreed not to execute against Dockstader and Dockstader assigned the rights under his policy to Brooks.

Brooks intervened in the coverage action and filed a third-party complaint alleging that Owners was in bad faith for failing to settle within policy limits, when Dockstader faced a significant likelihood of judgment in excess of limits.

The federal district court in the coverage action concluded that no coverage was owed, finding that “the average adult would expect the probability of nontrivial harm as a result of swinging a dumbbell close enough to someone’s head to scare them.” [This had been Dockstader’s argument as to his intent.] The court also concluded that there was no basis for a bad faith claim for Owner’s refusal to accept the policy limit demand.

Brooks appealed the bad faith finding. He argued that “the district court erred in holding Owners had no duty to accept Brooks’ settlement offers. In effect, Brooks asks us to establish a rule holding that insurers who have accepted a defense must also accept settlement offers within the policy limits—even where the insurer has filed a declaratory judgment action disputing coverage and the district court ultimately finds none.”

The Tenth Circuit declined to adopt such a rule. The court described its decision this way: Here, Owners embraced its rights under Utah law in seeking declaratory relief. And with the declaratory judgment action pending, Owners conditionally accepted Brooks’ settlement offer. It said, ‘[i]f there is coverage, will pay the policy limit of $500,000 to Mr. Brooks.’ Owners did not gamble in deciding whether to accept an offer or take the case to trial. If the Policy covered Dockstader’s conduct, Owners agreed to pay Brooks the Policy limit—trial was never a consideration. Moreover, in pursuing a declaratory judgment action, Owners bore the risk that the district court would determine coverage existed and it might be on the hook for any judgment in excess of Brooks’ settlement offers—even if the excess exceeded the Policy limits. So the risks associated with Owners’ conditional acceptance of Brooks’ settlement offers were borne by Owners not Dockstader. Owners’ risk paid off as it later received a court judgment, which Dockstader did not appeal, declaring that the policy at issue provided no coverage.”

As I mentioned, as the case did not involve an excess verdict, following an insurer’s failure to settle within limits, Dockstader is not a paradigm bad faith failure to settle scenario. However, it still offers some important take-aways:

First, an insurer that has a coverage defense, and one that it feels so strongly about that it will not want to accept a settlement demand within limits, should file a coverage action. That the insurer had done so here was a key to the court’s decision and why the insurer prevailed. Without doing so, the insurer can expect an argument that, if it knew it was not going to accept a settlement demand within limits, because of its coverage defense, then it should have taken steps to get the issue judicially resolved.

Second, as this court saw it, an insurer’s conditional agreement to settle within limits, subject to a later coverage determination, does not constitute bad faith failure to settle. It is not a situation where the insurer gambled in deciding whether to accept an offer or take the case to trial.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Hundreds Of Covid-19 Coverage Decisions: This One Was Most Significant

Inns-by-the-Sea v. California Mutual Ins. Co., 71 Cal. App. 5th 688 (2021)

|

|

|

| |

While the Covid-19 business interruption cases involve property policies, which are not the subject of this annual insurance coverage best-of, the story was just too significant to ignore here. Plus, many involved in liability coverage, and not normally property coverage, all of a sudden found themselves in the thick of Covid-19 business interruption cases. Many who have spent a career thinking that BI meant “bodily injury” were now using it to mean “business interruption.” So the story is relevant to CO readers.

As widely reported, state and federal courts issued hundreds of decisions – both at the trial and appellate level – addressing coverage for Covid-19 business interruption losses. It was a landslide win for insurers. According to Penn Law School’s latest numbers, insurers won 94% of cases before federal district courts and 72% at the state trial level. Insurers have also won every decision from federal circuit courts of appeal. This is Reagan-Carter, the Globetrotters vs. Washington Generals, Tiger at the 1997 Masters [final round on my wedding day, fyi.]. Even Ted Lasso couldn’t find anything positive in this for policyholders. As an aside, I addressed the state of Covid-19 business interruption coverage in a September 29, 2021 article in The Wall Street Journal. https://www.coverageopinions.info/WSJCovidRaid.pdf.

While the decisions numbered in the several hundreds, I believe that Inns-by-the-Sea v. California Mutual Ins. Co. is worthy of being called the most significant. Simply put, in determining that no coverage was owed for Covid-19 business interruption losses, the case has everything. To make this point, I am going to address the decision in list-fashion and not as a narrative discussion.

The Jurisdiction

There has been no shortage of policyholder angst about the vast majority of Covid-19 coverage decisions coming from federal courts. The oft-made policyholder argument has been that the coverage issue is a novel one and involving state law. Thus, the decisions on coverage should be made by state courts and not federal courts predicting state law. But Inns-by-the-Sea was decided by a California state court – not to mention at the appellate level and unanimous. In addition, in general, when it comes to insurance coverage, California is not one where policyholders usually complain about being (except on the Cumis statute independent counsel rate issue).

The Facts

The facts in Inns-by-the-Sea are those seen in just about every Covid-19 business interruption coverage case: a business -- here, a company with hotels on the California coast – was forced to close its doors on account of county orders designed to limit the spread of the coronavirus. So there is no argument that something about the facts at issue makes the decision different from all others.

The Policy Language

The business interruption policy language is the standard provisions that are contained in most policies: “We will pay for the actual loss of Business Income you sustain due to the necessary ‘suspension’ of your ‘operations’ during the ‘period of restoration’. The ‘suspension’ must be caused by direct physical loss of or damage to property at [Inns’] premises … . The loss or damage must be caused by or result from a Covered Cause of Loss.” So there is no argument that something about the policy language at issue makes the decision different from all others.

The Presence Of Covid-19 On the Premises

Many courts that found against policyholders had much to say about the absence of Covid-19 on the shuttered premises. This was an important factor in many courts’ decisions that the physical damage requirement for coverage had not been satisfied. Here, however, that was not an issue, as the court gave the policyholder the benefit of the assumption, for the purpose of its analysis, “that the complaint describes (or could be amended to describe) a scenario in which, at some point, a person infected with COVID-19 was known to have been present at one or more of Inns’ lodging facilities.”

The Court Considered The Popularly Cited Policyholder Case Law

In support of the argument, that the presence of Covid-19 satisfies the physical damage requirement for business interruption coverage, policyholders often point to a series of cases where courts found coverage for businesses shut down by the presence of substances that did not physically alter the structure. Such cases involve smoke, odor, ammonia, asbestos and others.

The Inns-by-the-Sea court considered these decisions at length, and rejected them, based on glaring distinguishing factors. First, the orders “reveal that they were issued because the COVID-19 virus was present throughout San Mateo and Monterey Counties, not because of any particular presence of the virus on Inns’ premises.” In addition, even if the virus had been present on the premises, and the Inns had to thoroughly sterilize them, the Inns “would still have continued to incur a suspension of operations because the Orders would still have been in effect and the normal functioning of society still would have been curtailed.” In other words, even if Covid had been present on the premises, and the Inns had to sterilize them, the Inns could still not have opened its doors.

Loss Of Use Is Not Physical Loss

The court rejected the argument that “the inability to use physical property to generate business income, standing on its own, . . . amount[s] to a ‘suspension’ … caused by direct physical loss of property within the ordinary and popular meaning of that phrase.” While the court cited to the Couch treatise to make this point – which some policyholders will say taints the opinion, on account of a conspiracy worthy of a John Grisham novel (a story beyond the scope here) – the court also made a point difficult to ignore. Not to mention it is tied to the policy language, which policyholders point to as what needs to be the most important source for an insurer’s decision.

Looking to the policy’s definition of “period of restoration,” the court stated: “The Policy’s focus on repairing, rebuilding or replacing property (or moving entirely to a new location) is significant because it implies that the ‘loss’ or ‘damage’ that gives rise to Business Income coverage has a physical nature that can be physically fixed, or if incapable of being physically fixed because it is so heavily destroyed, requires a complete move to a new location. Put simply, that the policy provides coverage until property ‘should be repaired, rebuilt or replaced’ or until business resumes elsewhere assumes physical alteration of the property, not mere loss of use.”

The Absence Of A Virus Exclusion

The court rejected the argument, that because ISO adopted a virus exclusion in 2006 (although not present in the policy at issue), it is an acknowledgment that a virus is capable of causing direct physical loss of or damage to property. But, in doing so, the court acknowledged that “it may be possible that in certain hypothetical situations a virus could cause a suspension of operations through direct physical loss of or damage to property.” But, as pled, the court stated: “this is simply not such a case.”

***

As Inns-by-the-Sea v. California Mutual Ins. Co. addresses the panoply of the issues that policyholders have raised, and then some, in support of Covid-19 coverage – and, especially, the jurisdictional one – I believe that it is worthy of being called the most significant decision out of the hundreds handed down in 2021.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 11 - Issue 1

January 3, 2022

Massive Disgorgement Settlement Not An Excluded Fine Or Penalty

J.P. Morgan Securities Inc. v. Vigilant Insurance Co., 2021 N.Y. LEXIS 2519 (N.Y. Nov. 23, 2021)

|

|

|

| |

I went back and forth on whether to include the New York Court of Appeals decision in J.P. Morgan Securities Inc. v. Vigilant Insurance Co. as a Top 10 coverage case of 2021. The issue is certainly significant – coverage for disgorgement, which has gotten a fair amount of attention lately. But I felt that the case is fact-driven, minimizing the extent to which it could affect cases nationally.

However, coming from the New York high court, the significance of the issue and the likely ability of some lawyers to still find it applicable or relevant to other cases, put it over the top. Not to mention that disgorgement claims, like this one, sometimes have huge amounts of money at stake.

At issue was coverage for Bear Stearns, for a 2006 settlement that the investment company reached with the SEC, on account of allegations that the firm facilitated late trading and deceptive market timing practices in connection with the purchase and sale of mutual funds. Facing a threat from the SEC, to commence a civil action and seek $720 million in monetary sanctions, Bear Stearns settled with the government, agreeing to make a $160 million “disgorgement” payment and $90 million payment for “civil monetary penalties.”

The court described the characterization of the settlement as follows: “Both payments were to be deposited in a ‘Fair Fund’ to compensate mutual fund investors allegedly harmed by the improper trading practices (see 15 USC § 7246). Further, ‘[t]o preserve the deterrent effect of the civil penalty,’ the settlement order directed that the $90 million payment—but not the disgorgement payment—was ineligible to offset any sums owed by Bear Stearns to private litigants injured by the trading practices. Bear Stearns was also required to treat the $90 million payment as a penalty for tax purposes.”

Seeking recovery, successors to Bear Stearns turned to numerous insurers’ policies that provided coverage for the company’s “wrongful acts” if there was a “loss,” defined as various types of damages, including compensatory and punitive damages, but not if the settlement qualified as “fines or penalties imposed by law.”