|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Michael Chertoff and I got ourselves situated in the seating area in his office. I told the nation's second Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security that I wanted to begin our conversation by going over his resume. The look on his face said "bring it on.”

A couple of degrees from Harvard – undergraduate and law. From there a Circuit clerkship followed by one for the Supreme Court -- Brennan. Partner at Latham & Watkins. Assistant United States Attorney under Rudy Giuliani in the Southern District of New York. Then the man at the top of the U.S. Attorney's office in New Jersey. Assistant Attorney General, involved in the drafting of the Patriot Act. Third Circuit Judge. A call from Bush 43 to serve in his Cabinet. A couple of books. We are now sitting in a corner office at his security firm, The Chertoff Group, overlooking New York Avenue in the nation's Capital.

|

|

|

|

| |

Chertoff nodded his confirmation that I had my facts straight. So I told him that I had to ask the obvious question: "How come you're such a slacker?" He laughed.

Chertoff credited the diversity of his career to a "willing[ness] to do something a little bit unplanned if it seemed like it made sense." But that makes him look like he can't keep a job, I joked. But I know better. Several of the positions he held are often-times short-term by their nature.

Chertoff's resume is staggering. There can't be too many lawyers in America who have one like it, I said. Chertoff humbly shrugged it off: "I'm sure there are other people." I went along with him. But I doubt it.

While diverse, Chertoff's career has a common thread of public service. This afforded him the opportunity to witness history, as well as be a part of it. I've taken the train two hours south to hear some of it. But looking backwards isn't all that's on my mind. These days Chertoff is actively involved in one of our greatest present and future threats – cyber risks. His just published book – Exploding Data – looks at cyber and privacy issues from a unique perspective.

Chertoff was a gracious host and in no rush to get rid of me, even after forty-five minutes. At my request, he moved our meeting from a conference room to his much more interesting office -- walls adorned with photos and mementos of a career at the highest ranks of government. The pay isn’t great in public service, but you get a lot of pictures, he joked.

Chertoff's office looks like that of a politician, but he is nothing of the sort. This is not a guy who has spent a lifetime kissing babies or eating corn dogs at the state fair. He answers my questions with measured responses and avoids tangents. He comes across as someone focused and serious in purpose, the sort of qualifications you'd hope for in a person keeping over 300 million people safe.

|

| |

The Law And Order Man And The Liberal Justice

Chertoff’s career is much about law and order. Justice William Brennan, Chertoff’s one-time boss, is one of the Supreme Court’s liberal lions. I noted this seeming incongruity. Chertoff saw my point, but it was overstated he told me. Brennan, Chertoff assured me, was no Pollyanna who “believed that criminals are all misunderstood people and we should feel sorry for them.” For this, Chertoff pointed to some of the criminal issues the Justice handled, such as bail.

Chertoff was working for Brennan in 1980 when the Justice authored a dissent in World-Wide Volkswagen v. Woodson -- the landmark civil procedure case addressing due process and personal jurisdiction. I joked that he was back in law school in Civil Procedure. Funny I should mention that he said, just a few days before, his law student-son, studying the decision and noticing its date, had asked his father about it.

Brennan was widely known for his humility. Chertoff saw that first-hand. He described the Justice having coffee every weekday morning with his clerks and wanting to meet their parents when they were in town.

|

|

|

|

| |

I shared my own Brennan-humility story. Brennan retired in 1990. I was a third year law student at the time. I sent the Justice a copy of the ABA Journal, featuring his photo on the cover, and asked if he would autograph it for me. Brennan complied, along with sending a note saying that he was "flattered that [I] should want it." Yeah, that's humility. I showed the letter to Chertoff and it brought a smile to his face. He told me he still has the letters Brennan sent him on the birth of his children.

Latham & Watkins And The Visit To Death Row

Even before entering the profession Chertoff was experiencing things few others had. He was in Scott Turow's section at Harvard Law School. Chertoff doesn't need to read One L. He lived it! He shared with me a story of a debate over property rights that spanned two classes. Chertoff was at the center of it. The story made its way into Turow's legendary memoir of the school's grueling first year.

Following his clerkship Chertoff made the not uncommon pivot to Big Law -- taking a position at Latham & Watkins where he handled a variety of litigation as well as death penalty appellate work.

The firm represented three death row inmates in Arkansas, successfully having their death sentences overturned. A young Associate Chertoff visited the Cummins Unit Prison in Grady, Arkansas, to meet with a death row client. The gravity of it lingers in the air as Chertoff recounted the trip and how unusual it was. . [I couldn't help thinking: "Toto, I've a feeling we're not in Cambridge anymore."]

But Chertoff's time doing criminal defense work would be short-lived. The U.S. Attorney's office was in his sights. In 1983 he joined the office for the Southern District of New York. At the time, Rudy Giuliani was at the helm and the future New York Mayor was focused of organized crime. This led to Chertoff serving as lead prosecutor in the famed Mafia Commission Trial, which brought down the heads of New York's five crime families. Following a three month trial, the eight defendants were convicted on all 151 counts for all manner of RICO and extortion charges. The bosses received 100 year prison sentences. Chertoff went on to serve as the U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey, taking over from would-be Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito.

While Chertoff would return to his old firm a decade later for a seven-year stint, doing white collar criminal defense work, his career trajectory was clearly public service.

September 11th And The Patriot Act

Chertoff had just started the head of the criminal division for the Department of Justice when September 11th hit. He described having one of those "big old car phones" and learning from his Deputy that planes had hit the World Trade Center. Chertoff headed to the Robert Mueller-headed FBI office. One the way he learned about the plane crashing to the Pentagon.

He was now in the thick of it, being "present watching on a video conference as the order was transmitted to shoot down the fourth plane." Chertoff said he remembers thinking "I never thought I would live to actually see something like this outside a move." After that, "the whole day was about figuring out who did it, who was on the plane, who were the hijackers and then what's going to happen next. We went into overdrive."

Just six weeks after the terrorist attacks, President Bush signed the "Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001" into law. The so-called Patriot Act was designed to give the government greater authority in tracking and intercepting communications.

Chertoff was involved in its drafting, offering the perspective from the Attorney General's Office. At the time, the nation was still shell-shocked and fear over the possibility of another attack was wide-spread. I suggested to Chertoff that, under such circumstances, any security provisions, possibility preventing a repeat, would have been passed. Perhaps, he told me. But was quick to explain that Attorney General Ashcroft did not "want to push the envelope and take advantage." Instead he wanted to "pick things that we've talked about for years that we think are important to do, get the technology updated to what's going on in the internet age [and] avoid the seams and lines that prevent us from sharing information."

May It Please The Court

In 2003 Chertoff, with aspirations to be a judge, began nearly two years of service on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. His aspiration was to be a judge. It was "now or never," he told me. So after a career trying cases, Chertoff found himself facing the other direction in the courtroom.

It was a wholly different experience. "A way to be contemplative," he explained, "after the frenetic behavior over the last year and a half with trying to deal with constant threats." And boy was it ever. Chertoff good-naturedly recounted being asked by the Clerk's office if he could handle an emergency matter. Sure he said. "I'll stay as late as you need." But he was confused. They were checking his availability in case something came up in the next few weeks. "I thought 'wow this is a different [situation] … from you've got 20 minutes before something blows up and you've gotta stop it.'"

But Chertoff still yearned for action and wanted every case assigned to him to be argued. The more experienced judges, he explained, needed to quell his enthusiasm for the courtroom, pointing out that not every case needed to argued. "Well, let's not go wild here," they cautioned. Chertoff soon came around to seeing what they meant.

The President's Cabinet

Chertoff said he was content with the life of an appellate judge. But, in 2003, the call from the White House came. Chertoff was tapped to serve as President George W. Bush's Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security. Chertoff had 218,000 employees under him. If DHS were a city, it would be just about the hundredth largest in the country. Frenetic was back.

DHS is a massive organization. Is it just too big?, I wonder. Chertoff needed less than a second to say "no." The concept of having centralization of security related functions "makes a lot of sense."

But what about FEMA? What does disaster response have to do with keeping the bad guys out of the country? But that also makes sense, Chertoff said: "To really do security you've got to do response too." Not to mention, he explained, FEMA does not have a lot of assets. So it benefits from the ability to use the assets of the Coast Guard and Customs and Border Protection in rescues.

Chertoff headed DHS during Hurricane Katrina and has taken criticism for FEMA's response to the handling of it. Is that hard to hear? "You learn you have to take criticism," Chertoff told me. "I will say that when we started down the road to Katrina the rule was that state and local government are the first responders and the federal government supports. I don't think they ever had a circumstance where the Mayor was just holed-up in a hotel room and didn't do anything and the Governor was checked out too. They didn't order the National Guard and they didn't have a plan to evacuate people. So all of a sudden it was dropped in our lap with about a day to figure out what to do." But despite this explanation, Chertoff said he "understands politics and it was an opportunity to take shots at Bush. And it was probably ill-advised for him to take that picture in the plane."

Chertoff took the opportunity to say that the Coast Guard rescued 30,000 people – "a huge accomplishment." He also pointed out that the handling of the Katrina response led to creating a plan and capability for future hurricane response.

Exploding Data: Cyber, Privacy, Data And The Loss Of Autonomy

These days Chertoff's focus is risk management and cyber security. He heads the near ten year old Chertoff Group, which provides a host of services in the area. For example, Chertoff explained that this includes advising companies in the financial and utility sector on "what are the cyber and physical risks. Since you can't cut yourself off from the cyber space if you are a commercial enterprise, how do you organize your strategy to secure your key assets in such a way that allows you to conduct business. But that doesn't open the portal to people getting into the things that could fatally damage the business."

Four Star General Michael Hayden, former Director of the CIA and former head of the National Security Agency, has his office down the hall. I walked past legendary CIA man Charles Allen's office. There is some serious business going on here. Indeed, they know their security. My effort to steal the cool visitor badge, for a souvenir, was unsuccessful. I was nabbed at the front desk. I had to settle for a pen from the jar in the waiting room. Not the same.

As the former head of DHS Chertoff naturally has a wealth of knowledge on the subject. That Chertoff wrote a book about it is not surprising. But his recently published Exploding Data - Reclaiming Our Cyber Security In The Digital Age is much more than the tale of lost privacy that we experience on account of sharing so much of our personal data.

As Chertoff described it, our fear, of George Orwell's 1984 coming true, has been realized. But not for the reasons we anticipated. We worried that Big Brother "might force his way into our home," Chertoff said. But that's not necessary. "We are currently rolling out the red carpet to welcome him."

In Exploding Data, Chertoff takes a more unique approach to the subject. That our sharing of personal data has led to a loss of privacy is too narrow of a description of the risks we face. "That ship has sailed," Chertoff told me.

What is now at stake is a loss of autonomy. "What we should care about," Chertoff cautioned, "is when people use the data for a purpose other than what we intended. . . . At some point the data can be used to really manipulate or even coerce you." "Soft totalitarianism," he called it.

Chertoff shared an actual story of someone going through a divorce and emailing with their lawyer. On account of the right of the email provider to monitor emails, in an automated fashion, the soon-to-be divorcee began receiving ads for a dating site. "Wow!," Chertoff said. "If when I was in the government, I had, without a warrant, monitored email traffic between someone and their lawyer, I'd be in jail. . . . That was one of the stories that made me think people don't really understand what's at stake with the data."

But isn't this just the price of using all of this wonderful new technology?, I suggested. No, Chertoff replied: "If I want to use your data for a purpose other than the original purpose, I have to ask your permission. Maybe I have to pay you for it. If I'm going to make money using your data, which is the new gold, maybe you should be compensated for it. But you should have a right to say 'yes' or 'no.'" Chertoff offered one possible solution. "Maybe a service you get, if you are not willing to let them use the data, they'll say 'then were going to charge you a fee,' like a pay wall with a newspaper. The point is to give people a real choice and not simply force them to surrender what turns out to be the most valuable thing they have."

|

|

| |

*** |

Michael Chertoff has spent a lifetime holding some of the highest positions in government and the judiciary. He has witnessed a lot of history. Most times, in fact, he’s been in the room where it happened. |

| |

| |

| |

[Elizabeth Vandenberg, a 2L at the University of Iowa College of Law, assisted with this article.] |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Insuring Your Thanksgiving Fouls: Uncle Sam’s Drooling Saliva And The Turducken Fight

|

|

|

|

|

| |

The amount of time and effort involved in hosting a Thanksgiving dinner is tremendous. Believe me, I know. I see what my wife goes through.

But while she’s crazy-busy dealing with the bird, stuffing, mashed potatoes, three kinds of cranberry sauce, five types of vegetables, side dishes I’ve never even heard of and five different pies (including one with a gluten free crust -- for her annoying cousin Barry, who doesn’t stop talking about cross fit), it’s not like I don’t have my own challenges. The Lions are 3-5 so far this season. And they’re not going to turn into the 1972 Miami Dolphins between now and November 22. Watching that Lions – Bears game is going to be a huge effort for me. It might be more enjoyable to stand at the sink and peel the potatoes.

But that’s not all I have to contend with. It is my job to make sure that the Spencer family’s annual Turkey Day blow-out doesn’t turn into a financial catastrophe worse than taking the Lions with the points. That give me the task of ensuring that our homeowner’s policy provides adequate coverage for all of the risks associated with having 20 people in the house -- each consuming as many as 4,500 calories -- except cousin Barry.

Thanksgiving is rife with risks for which insurance is needed. There are insurance companies named Mayflower Insurance Exchange, Pilgrim Insurance Company, Plymouth Rock Assurance Corp. and Pie Mutual Insurance Co. Really. I’m not kidding. All these companies must do is insure the hazards of Thanksgiving.

Thanks to reading my homeowner’s policy, we had liability coverage for all of the following Thanksgiving dinner mishaps over the years:

Aunt Mildred nearly choked to death on that plastic thing in the turkey that pops up to tell you when it’s cooked. She said she didn’t want to sue Butterball, because it’s her favorite company and “wouldn’t dream of doing that to them.” But she was fine suing me. Coverage was provided for “bodily injury” caused by an “occurrence.”

My wife told her sister that she’s grateful we stopped going to cousin Gladys’s for Thanksgiving because her turkey was always dry. Gladys overheard this, was outraged and sued my wife for defamation. Coverage was provided for “personal and advertising injury.”

Annoying cousin Rex insisted on showing off his new drone, along with pontificating about how drones will be changing the way we live. The drone crashed onto the hood of my neighbor, Frank’s, Jag. Coverage was provided for “property damage” caused by an “occurrence.” Drones may not change the way we live, but one drone changed the way Frank drove for a week. He had a Toyota Corolla rental.

Cousin Mitchell brought all of the gear needed to deep fry a turkey. It’s perfectly safe, he assured me. Coverage provided for the three houses that went up in flames. Cousin Barry commented that that’s what happens when you cook an unhealthy turkey.

My wife, accused by Aunt Shirley of using her mother’s string bean casserole recipe, was sued for theft of trade secrets. Coverage was provided for “property damage” caused by an “occurrence.” [See “Wow! Court Holds That Trade Secrets, Being Tangible Property, Are “Property Damage,” discussed in this issue of Coverage Opinions.]

89 year old Uncle Max told Cousin Cindy’s two-year old son, Cody, that he was going to take Cody’s nose off. Max grabbed Cody’s nose -- but pulled too hard. Cody’s nose was detached. It was alleged that I was responsible because I should have known that Max sometimes pulls too hard on kid’s noses. Coverage was provided for “bodily injury” caused by an “occurrence.”

Potential coverage denial prevented when Uncle Peter stopped me from punching Cousin Phil for saying, for the ninth straight year, that we really ought to have a turducken.

And liability risks aren’t all that should be on your mind. Property losses have abounded too. Once again, thanks to the homeowner’s policy, we were safe and sound in all of the following scenarios.

Uncle Charlie used the fancy guest towels in the powder room. Sure, he was a guest. But even guests aren’t allowed to use them. The guest towels were covered property under an all-risks homeowner’s policy.

Aunt Matilda confused the urn, holding our beloved Scooter’s ashes, with a gravy boat. A cocker spaniel’s ashes are covered property under an all-risks homeowner’s policy. But a dispute arose over how to value them. It’s going to appraisal.

93 year old Uncle Sam fell into a deep tryptophan–induced sleep on the sofa after dinner. A steady stream of saliva dripped out of his mouth for an hour. The stained sofa cushion was covered property under an all-risks homeowner’s policy.

The first Thanksgiving was very successful. That’s because the people sitting around the table didn’t know each other.

|

That’s my time. I’m Randy Spencer. Contact Randy Spencer at

Randy.Spencer@coverageopinions.info |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

YeeHaw: You Won’t Believe Who Reads Insurance Key Issues |

|

|

|

| |

The iconic Times Square Naked Cowboy is a smart guy. He doesn’t want to go bare in the event he suffers any losses standing out there at 45th and Broadway. This is why he reads General Liability Insurance Coverage – Key Issues In Every State.

Not only that, he has the 4th edition of Key Issues. The Naked Cowboy told me that he didn’t want to get caught with his pants down by not having the most up-to-date version – with over 900 more cases than the now long-in-the-tooth 3rd edition.

If The Naked Cowboy uses Key Issues – and the 4th edition -- so should you.

About Insurance Key Issues:

50-state surveys of liability coverage issues are not unique. But there are two things that make them unique in Insurance Key Issues:

• All of the 50-state surveys – which are extremely current -- are conveniently available in one location.

• At nearly 1,000 pages covering 20 issues, the extent of detail and case law is far more extensive than many 50-state surveys. There is often enough information to provide one-stop shopping to answer your question. If not, you’ll know exactly where to begin your additional research.

Visit the Insurance Key Issues website: www.InsuranceKeyIssues.com

To see what it’s about, check out the sample pages:

http://insurancekeyissues.com/SamplePages.pdf

The Insurance Key Issues Promise: If you like Coverage Opinions, rest assured that the same effort has gone into Key Issues for the past ten years.

Visit the Insurance Key Issues website: |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Insurance For Plaintiffs’ Attorneys Losing A Contingent Fee Case

Q&A With A Co-Founder Of Level Insurance On This Really Unique Product

|

|

|

|

|

| |

I have long remarked that the insurance industry does a good job of offering products to address the risks associated with unique and new exposures. I’m referring to legitimate risks -- not those silly policies that the media loves to talk about, that provide insurance for things like Liberace’s hands, Tom Jones’s chest hair and Michael Flatley’s legs.

A couple of years ago I did a story on Level Insurance, a then-new company offering one of most unique insurance products I had ever seen: Litigation Cost Protection – coverage for plaintiffs’ attorneys for their costs in the event that a contingency fee case ends in a defense verdict.

The concept is simple. A lawyer-policyholder takes a case on a contingency fee, it goes to trial and there is a defense verdict. He or she can now recover their cost disbursements, such as expert witness fees, travel expenses, court reporter fees, trial exhibit costs and all other monies spent in furtherance of the case. The policy does not use qualifiers like reasonable costs. The attorney is reimbursed for whatever was spent. If the case settles or is disposed of on summary judgment, no coverage is owed. The online application process takes minutes and the premium is simple - 7% of the coverage limit regardless of the type of case (exclusive of taxes and fees). The limits available are between $3,500 and $250,000.

Litigation Cost Protection recently received important regulatory wins that will no doubt make the policy more attractive to potential purchasers: The Bars of Florida and North Carolina both issued ethics opinions stating that a lawyer can purchase the policy and include the premium in the costs charged to the client following a settlement or win at trial. To do so, both opinions made clear that the lawyer must follow several proscribed steps, which include making certain disclosures to their clients.

I recently checked-in with Level Insurance co-founder Larry Bassuk to see how things have been going for the company and its Litigation Cost Protection. To learn more about this really unique product, what it took to get it off the ground and the challenge of finding an insurer, willing to underwrite a policy for the benefit of plaintiffs’ lawyers, check out my Q&A with Larry here.

1. What was your lightbulb moment for Litigation Cost Protection?

I was inspired by a mentor to explore innovative business opportunities within the legal industry. As a practicing trial attorney, the law ‘business’ is the one I know best. As I brainstormed opportunities, I noticed that finance and insurance tools, which are routinely leveraged in other industries, were largely unavailable to attorneys. This observation lead to the idea that an attorney’s financial exposure in a contingency fee relationship could be mitigated with insurance. It was just a matter of applying established insurance principles to that particular risk.

I approached Justin Leto, who is now my law and business partner in several ventures, with the raw concept. Justin was a solo practitioner at the time, and is a very business-savvy attorney. We refined the concept and embarked on the extremely fulfilling experience of turning our theoretical ideas into a national business.

2. The road from concept to market must have been a challenging one. Can you describe what that journey was like.

It was indeed a challenge, however, the experience has been extremely rewarding. There were essentially three stages to taking the concept to market. First, we had to validate the concept [of insuring case costs] and establish that it could serve as the premise for a viable insurance program. We then worked with a prominent actuarial consulting firm for nearly one year for the purpose of gathering, analyzing and interpreting the data and ultimately modeling the risk. As a result, we had something concrete and substantiated that we could present to insurance carriers. The decision to work with actuaries early on, although it took a lot of time, effort and resources, was a critical decision.

Armed with what was, in essence, the structure of the insurance program (risk modeling, pricing, assumptions, etc.) and extensive market research, we then shopped the coverage to national insurance companies. The carriers (largely household names) were intrigued by the coverage and recognized its potential, however, many were concerned or downright turned off by the notion of providing insurance coverage to trial lawyers. This part of the process was very challenging. We ultimately teamed up with an exceptional carrier partner, Aspen Specialty Insurance Company.

Next, we had to build the business itself. This included raising money and building out a fairly sophisticated, online-based underwriting and payment system (our entire process has always been 100% online and only takes a few minutes). We created and then built our brand, Level Insurance, and deployed a national marketing campaign to promote the business, which is something we still engage in daily.

3. LCP is such a unique idea. Has that been a challenge to selling it?

Educating our market has been a challenge. No matter the idea, reaching the market and competing for customers’ attention is an ongoing process. Because Litigation Cost Protection is a new concept, when attorneys first learn about it they often respond with equal parts curiosity and skepticism. Since Justin and I are both practicing attorneys (along with Lindsay Milstein, who joined Level about a year ago), we are able to explain the coverage in ways that our customers understand. We can answer hyper-technical questions, which increases each potential new customer’s confidence.

Ultimately, once we have someone’s attention, we are met with enthusiasm and have been very successful in acquiring new customers.

4. How have plaintiffs’ attorneys been using LCP?

First and foremost, trial attorneys are using Litigation Cost Protection like they use all other insurance coverage—to mitigate their risk and to gain peace of mind. We routinely sell $250,000 policies back-to-back with $10,000 policies, which goes to show that our customers have varying risk appetites and strategies. Some attorneys use Litigation Cost Protection for certain types of cases (for example, all of their product liability cases) while others use it for cases that exceed a certain cost-threshold to litigate. We designed this coverage to be flexible. Attorneys can pick and choose which cases to cover and they customize their limits for each case.

Across the board, I hear that our customers feel more confident litigating their covered cases, feel more comfortable spending money to litigate their cases and overall have more peace of mind knowing that their risk exposure is controlled.

We enjoy hearing creative ways in which our customers are using their coverage to their benefit. For example, some attorneys are sending their Declarations Page to opposing counsel, with the message that they should inform the insurance adjuster assigned to the case that the plaintiff’s attorney has Litigation Cost Protection and is committed to trying the case unless a reasonable offer is made. This has reportedly enhanced settlement negotiations and results.

I’ve been advised that lenders are offering better terms, rates and higher amounts of financing for cases that are backed by Litigation Cost Protection. In fact, after hearing this many times, we included a loss payee endorsement form as part of the application policy, so attorneys can name their lender as a loss payee. This has further facilitated the process and provided value to our customers.

5. How have the sales and claims experience been?

Although I cannot provide specifics, I’ll share that we have grown from offering Litigation Protection in only five states to offering it nationally. We have sold policies in approximately 35 states and nearly all of our customers have incorporated Litigation Cost Protection into their practice, meaning they routinely obtain coverage. We are proud of our company’s growth and we continue trending upwards. Our claims experience is in line with our projections, and we pride ourselves in handling claims expediently, easily and fairly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Coverage Opinions

Turns 6!

|

|

|

|

|

| |

I am excited to report that this issue marks the 6th Anniversary of Coverage Opinions. That’s the iron anniversary if you are thinking about a gift. I could use a new wok.

Six years of hardcore coverage, a look at the lighter side of the law, interviews with famous and unique lawyers, insurance contests, “Key Issues” plugs, dealing with Randy Spencer’s contract demands, the too-popular Coverage Opinions pen giveaway, Q&As with fellow coverage lawyers, Boy George following Coverage Opinions on Twitter (seriously), a picture of John Grisham reading his Coverage Opinions interview (CO’s high water mark) and random other stuff that I can’t exactly categorize. If there has ever been a labor of love in my career, this is it. As in all endeavors of this sort, on some days there is more of the former than the later. But, despite some challenges, I could not be happier with how things have gone for CO over the past six years.

Of course, there could be no six-year anniversary to mark if it were not for you – the dear Coverage Opinions reader. I can’t thank CO readers enough for taking the time to do so, despite having such busy schedules and being inundated with other newsletters, and the like, competing for their time. I also appreciate all of the reader mail that I receive – mostly positive, but sometimes taking me to task for something I said or didn’t say -- and that’s fine too. I am also lucky for the friendships that I have made with CO readers who reached out about something they saw. Please accept my sincere appreciation for enabling me to send a Coverage Opinions six-year anniversary announcement.

Comments, questions, criticism, hate mail, how’s my driving, ideas for making CO better -- I’m all ears. Please write to me at maniloff@coverageopinions.info

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

A Treat: The Wall Street Journal Published My Op-Ed On Halloween And The Law

|

|

|

|

How exciting. On October 30th, the Wall Street Journal published my Op-Ed on Halloween and the law. This follows my Op-ed on hot dogs and the law. Before that it was sports fans and the law. And two on baseball and the law. [And then I actually had a serious one on a legal issue.]

This is what you write about for The Wall Street Journal editorial page when you are not smart enough to write about supply side economics or trade policy.

On Halloween things happen that never would on any other day. But what about judges? Do they approach the law differently when Halloween plays a part in a dispute?

I hope you’ll check out my WSJ Op-Ed that addresses this question:

http://www.coverageopinions.info/WallstreetHalloween2018.pdf

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

New Album From Culture Club: Boy George Follows Coverage Opinions On Twitter

(For Real)

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Culture Club just released its first new album in 20 years – Life. Why do I tell you this? Because Boy George follows Coverage Opinions on Twitter. I met him a few years ago and asked if would follow Coverage Opinions. He was a great sport and did it. And he hasn’t unfollowed CO in all that time. Of course not – Boy George is no chameleon.

Congratulation George and Culture Club on the new album. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Another “Ineffective ROR” Case: The Issue Insurers Cannot Ignore

|

|

|

|

Have Me Visit Your Office To Put On My “50 Item ROR Checklist” Seminar

For the past few years I have been counseling clients, addressing in Coverage Opinions, annual top ten cases of the year articles, at client seminars, webinars, industry seminars and to the guy next to me in line at Trader Joes, that for a reservation of rights letter to be effective it must fairly inform the insured of the reasons why the insurer, despite that it is providing a defense to the insured, may not in fact be obligated to provide coverage for certain claims or damages in a suit. In other words, an ROR that cites some facts, and then quotes some policy provisions, and then says, viola, we reserve our rights, is at risk for being found to be ineffective. Translation - the insurer has waived its defenses.

Several decisions, from state appellate courts over the past few years, have found ROR letters to be ineffective because they did not fairly inform the insured, i.e., adequately explain, with specific facts tied to the potentially relevant policy provisions, why coverage might not be owed.

And this trend continued with the just-adopted ALI Liability Insurance Restatement, which includes this fairly inform standard in its ROR requirements section.

One of the oldest cases to address the “fairly inform” standard for ROR letters is Bogle v. Conway, 433 P.2d 407 (Kan. 1967) from the Supreme Court of Kansas in 1967. I was just 11 months old when it was issued -- and flipping through insurance coverage picture books. But 50 year old cases often times do not get people’s attention.

But, on Friday, October 26, the Supreme Court of Kansas made clear that Bogle is alive and well. In Becker v. Bar Plan Mutual Ins. Co., No. 113,291 (Kan. Oct. 26, 218), the Kansas Supreme Court cited Bogle’s “fairly inform” standard to determine that an ROR may not be effective because it was not timely issued. Granted, this is not the issue of an ROR not containing sufficient information to be effective. However, Friday’s Kansas high court decision made clear that Bogle’s “fairly inform” standard for ROR letters is the law. By addressing Bogle, the Kansas Supreme Court removed the belief, that sometimes exists, that old cases are less important or, somehow, have expired.

A quick look at Bogle… The court held that an ROR was ineffective (even where the insured consented to it in writing) because it did not adequately explain that the insurer was reserving its rights, for an auto claim, based on a racing exclusion. Here are the key passages from the Bogle decision:

“We turn now to the September 30, 1963, instrument upon which appellant relies. It is more vaguely and ambiguously drafted than that held insufficient in Henry. It makes no mention of any exclusionary clause in the policy or of any purported factual basis upon which a denial of coverage might be predicated; it does not tell what right of the insurer to deny liability was contemplated, nor why; it contains no reason or basis for the statements which are made, and finally, concededly, no disclaimer of liability is stated.” Bogle at 412.

“Appellant [Insurer] argues it should not be necessary for an insurer to detail fully in a reservation instrument all of its rights inasmuch as all the parties want to do is maintain the status quo. Much more is involved: the parties are hardly upon equal footing absent information to the insured as to what that status quo is and means. It has been said that good faith, the essence of insurance contracts, demands that the insurer deal with laymen as laymen and not as experts in the subtleties of law and underwriting.” Id.

Becker, as a reminder that Bogle is alive and well, continues the trend of courts saying that ROR letters must “fairly inform.” All of this is not to say that an ROR, that does not “fairly inform,” is effective if a state has not specifically said otherwise. These are simply courts that had the opportunity to specifically say what an ROR must do.

Have Me Visit Your Office To Put On My “50 Item ROR Checklist” Seminar

For the past few years I have traveled the county – to client offices -- putting on my “50 Item ROR Checklist” seminar. It addresses the “fairly inform” standard in detail - and many other things that should be included in ROR letters to have them (1) achieve their purpose and (2) avoid having them found ineffective (also based on case law lessons).

Let me know if you are interested in having me stop by your claims office to do my “50 Item ROR Checklist” seminar. Yes, 50 sounds like a lot. But you’d be amazed what needs to be in a proper ROR letter.

The seminar is very practical – people tell me that they used things learned from it as soon as they get back to their desks. And we’ll have some fun. Yes, the material is serious; but I promise it will also be light and we’ll share some laughs. And I’ll bring along a copy of the 4th edition of Insurance Key Issues for the office.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

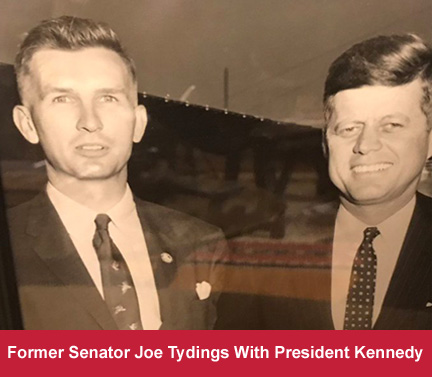

In Memoriam: Jerry Oshinsky On The Passing Of Joe Tydings

U.S. Senator Turned Policyholder Coverage Lawyer

|

|

|

|

|

| |

On October 8, 2018, Joe Tydings, a Democratic Senator from Maryland from 1965 to 1971, died at age 90. I saw a brief note about his passing on Twitter. But, being unfamiliar with Senator Tydings, I didn’t give it much thought. Then I received an email from Jerry Oshinsky, of Kasowitz’s L.A. office. Now, all of I sudden, I was fascinated by Joe Tydings. It turns out that politics was only one of Joe Tydings’s careers. Another was policies. He was coverage counsel to policyholders.

Jerry was a long-time friend and colleague of Joe Tydings. He shared with me, and for Coverage Opinions readers, the following moving tribute to the life of the Senator-turned-policyholder lawyer.

Remembering Joe Tydings

By Jerry Oshinsky

Sadly my wife Sandy and I recently learned about the death of our old friend, law and tennis partner, former Maryland Senator Joe Tydings (2 days after Sandy’s 95 year old mom also had died.)

We first met Joe when he joined our policyholders’ insurance coverage practice at Anderson Kill Olick & Oshinsky, PC. I interviewed Senator Tydings (“call me Joe”) in D.C., after he left Finley Kumble, and told him that I was chairing an insurance program in New York City the next day. Joe came to the program and the rest is “history.”

At the time (1988), Maryland was an unfavorable venue for policyholders seeking insurance coverage from insurance companies. I suggested that his role in our practice would be to “make Maryland safe for policyholders.” And did he ever!! Maryland had held that the only policy that counted, in cases where pollution had occurred over a long period of time, was the last policy in the sequence, referred to by the courts as manifestation or discovery of the alleged injury or damage. The problem with that rule was that, by that time in the pollution sequence, our clients’ policies contained blanket exclusions for pollution. Joe jumped head first into the arena and persuaded the Maryland courts that all of the policies from the first polluting event until the discovery were available to provide coverage, following our lead in the historic 1981 decision in Keene v. INA that had applied the same continuous coverage principle to cases involving exposure to asbestos. The early policies did not contain the later imposed exclusions for pollution or asbestos and provided ample insurance coverage for our clients.

Likewise, the conservative Maryland courts had held that EPA orders to clean up pollution were not covered by insurance because they supposedly were “injunctive” and did not seek “damages” covered by insurance. Once again Joe got that case law overruled, bringing Maryland law in line with earlier precedent that we had established in other jurisdictions.

Joe introduced us to Mark Kolman from a Maryland firm who joined us and Mark became our top trial lawyer not only in Maryland, but nationally. Joe also brought in Nancy Hogshead as a summer law associate who is now very prominent in critical public affairs as the CEO of Champion Women. This is an organization leading national efforts, in all areas for Women equality in sports, including Title IX enforcement in Athletic departments, and compliance with modern standards of equality in the workplace. Nancy tied for the gold in the 100 meter swim in the 1984 Olympics among her three gold medals and one silver. We played the video of the dead heat in our conference room and, while knowing the result, everyone cheered for a very slightly different outcome! But it was okay.... two for the USA!

I recall that Joe had similar success for New Castle County, Delaware and Coors Beer in Colorado, among others. He also always provided wise counsel on life, politics, culture, and ethics – or whatever topic he might be asked.

In the 4th Circuit, the custom is that Judges come off the bench and shake hands with each attorney after the argument. Joe received that treatment in the 3rd Circuit after his argument in the New Castle County case.

On a personal note, Joe’s popularity was such that, at his marriage ceremony in about 1990, on the campus of his beloved University of Maryland, his guests included Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Byron R. White. I sat at one table with Justice O’Connor and Sandy at another with Justice White. Both Justices spoke beautifully about their fondness and respect for Senator Tydings. (Justice White wore two different colored shoes to the wedding in his apparent haste to be on time.

JFK had suggested in 1963 that Joe run for the U.S. Senate and Joe indeed was elected in 1964. Ironically, when Joe ran for re-election to 1970, he lost by about 1% to Glenn Beall, Jr., after Joe had defeated Glenn Beall, Sr. six years earlier by 63% to 37%. Beall Junior was heavily supported by the NRA, who Joe had challenged even in that early time, and that was believed to have cost him the election. History does have a way of repeating itself. Joe played a prominent role in defeating two of President Nixon’s Supreme Court nominees in light of their opposition to civil rights. Joe’s principles were unshakeable. If he had been re-elected, as a close friend of the Kennedy family, he might have been a viable national candidate in 1976 or 1980, although it would have been interesting in 1980 with Ted Kennedy making a play. Conceivably, as a Marylander, and if he had kept his Senate seat, and as a Kennedy favorite, Joe might have shifted enough votes from Carter and swung the Nomination to Kennedy. Maybe too speculative, but it is never easy to predict the past!

Joe had these great pictures in his office including the Yalta Conference signed by every participant except Stalin. (Joe’s grandfather, Joe Davies, was the American interpreter). Joe sought out Svetlana Stalin, who would not sign, and explained in a letter to Joe that it was because of her disagreement with his politics! There was another photo of a tall, lanky Joe at age 20, talking with President Harry Truman. Joe also had a number of pictures with the Kennedys interspersed on his office credenza. Joe’s office was its own snapshot in history.

Joe’s adopted dad Millard Tydings was a friend of FDR; elected to the Senate four times and one of the very few in government to stand up publically to Joe McCarthy and the “Red Scare”.

Joe also was a favorite tennis partner of me and Sandy. Given his height (6’4”) and athleticism, probably developed from his log canoe rowing experience and his college sports days, he was a formidable player and never missed a serve. Sandy and I often played doubles against Joe and his partner at the time (Kate Clark in later years) and he would proclaim with a chuckle that the secret of his tennis success was “don’t hit the ball to the lady in the blue tennis shirt!” (Sandy!)

I can’t recall exactly when, but probably in the early 1990s, my partner Lorie Masters and Sandy and I were invited to hear Joe speak at a gun control rally. We then saw a different Joe: Joe the staunchest anti-gun advocate; Joe on the stump; Joe who the country never really appreciated; Joe, our immortal friend.

After Joe moved with our band of about 35 lawyers in 1996 to what became renamed as Dickstein Shapiro Morin and Oshinsky LLP, Sandy and I were having lunch with Senior Partner David Shapiro and Joe. David was the antithesis of Joe in many ways, height and weight differentials perhaps most prominent. As we walked, and Joe bounded ahead of us back to the office, David said: “look at that son of a gun! Look at him!”

That is my lasting image of Senator Joe Tydings—bounding ahead of us.......

October 12, 2018

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

ISO Files Endorsements To Address Xia Decision - Washington’s Adoption Of “Efficient Proximate Cause” For Liability Policies

|

|

|

|

In April 2017 the Washington Supreme Court shook up the coverage world, especially Washington, when it issued its decision in Xia v. ProBuilders Specialty Insurance Company. On one hand, the Washington high court held that carbon monoxide, released from a negligently installed vent, attached to a hot water heater, was a “pollutant.” At issue were claims for bodily injury by a homeowner against a home builder. So far this is routine. Lots of courts – those that apply the pollution exclusion broadly (and not simply to traditional environmental pollution) – would likely have reached that same determination.

However, the Xia court still held that the pollution exclusion did not apply. The court got to this result by adopting the “efficient proximate cause” rule, which provides that coverage is owed if a covered peril sets in motion a causal chain, the last link of which is an uncovered peril. This is usually seen in property coverage cases. However, the court noted that there was nothing to say it couldn’t apply to any type of policy.

Applying the “efficient proximate cause” rule, the court held that the pollution exclusion did not apply. The court determined that the efficient proximate cause of the injuries was the negligent installation of the hot water heater. Because this was a covered occurrence, that set in motion a causal chain, that led to discharging toxic levels of carbon monoxide, being an excluded peril, the pollution exclusion was not applicable. In other words, the pollution exclusion did not apply because two or more perils combined in sequence to cause a loss – one covered and one not -- and a covered peril was the predominant or efficient cause of the loss.

ISO not long ago responded to the Xia decision with the filing of endorsements designed to address it. While I do not know the status of the filing, a July 18, 2018 ISO Circular states that the new forms would be applicable to all policies issued on or after January 1, 2019.

The ISO response does not attempt to “contract around” the Xia decision, which the Washington Supreme Court suggested could be done. In other words, the endorsement does not state something to this effect – this exclusion still applies even if the efficient proximate cause of the injury or damages is a covered occurrence. Instead ISO addressed the decision through the adoption of an “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit.”

There are several similar endorsements, each for different policies, contained in the ISO Circular. The commercial general liability endorsement states as follows:

A. The following is added to Paragraph 2. Exclusions of Section I – Coverage A – Bodily Injury And Property Damage Liability, Paragraph 2. Exclusions of Section I – Coverage B – Personal And Advertising Injury Liability and Paragraph 2. Exclusions of Section I – Coverage C – Medical Payments:

1. If an exclusion under the terms of this Policy applies with respect to “bodily injury”, “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury”;

and

2. The efficient proximate cause, in accordance with the law of the State of Washington, of such “bodily injury”, “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury” is not also excluded under the terms of this Policy;

then:

a. The exclusion referenced in Paragraph A.1. above does not apply to such “bodily injury”, “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury”; and

b. Coverage provided under this Policy for such “bodily injury”, “property damage” or “personal and advertising injury” is subject to the Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit as described in Paragraph B. of this endorsement.

Essentially, the endorsement provides that, if an exclusion would have precluded coverage, but the exclusion is rendered inapplicable, on account of the efficient proximate cause rule from Xia, then the exclusion does not apply. In other words, the endorsements accepts that Xia may preclude the applicability of an exclusion. However, in such case, while the claim may now be covered, it is subject to the newly created “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit.” The amount of this limit – which in subject to the general aggregate and products-completed operations aggregate limits – is listed on the endorsement. The Circular does not address what the “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit” may be. Presumably this is an amount to be determined by each insurer based on its concern for the potential loss of exclusions via Xia.

This aspect of the endorsement seems workable. In the end, the impact of the endorsement will be tied to the amount of the Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit and how it affects exhaustion of other aggregate limits.

But where the endorsement may prove problematic is with respect to defense costs associated with a claim that comes within the “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit.” The endorsement is designed to include such defense costs within the “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit.” In other words, such claims are not treated as defense costs supplemental. However, only defense costs allocable to a claim, within the “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit,” are subject to this new aggregate limit.

Allocation of defense costs, between different claims in the same suit, is not always easy to accomplish. Some courts recognize that tasks performed by counsel, in defending a suit, often overlap between the covered and uncovered claims. Defense counsel’s work cannot always be pigeon-holed to specific claims. Even California, which is favorable to insurers in permitting allocation of defense costs between covered and uncovered claims, recognizes the practical challenges of achieving it. Insurers using an “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit” endorsement may be up against this issue when it comes to attempting to include defense costs within the aggregate.

There is also likely to be a question of determining to which claims the “Efficient Proximate Cause Aggregate Limit” endorsement applies. The endorsement simply states “Washington” in the title. On one hand, since the endorsement is based on the treatment of claims under Xia, its applicability is intended for claims governed by Washington law. If a policy is issued to a Washington insured, and the claim arises in Washington, then it’s clear-cut. Less clear may be a policy issued to an insured outside of Washington and the claim arises in Washington. Or if a policy is issued to an insured in Washington and the claim arises outside of Washington. In some cases, the endorsement is likely to introduce a choice of law issue into the equation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Ryder Cup Fan Injury: Commenting To Golf.com On My Favorite Tort Case

|

|

|

|

I have long had a fascination with courts’ handling of claims, brought by fans, who were injured by a foul ball while a spectator at a baseball game – and sometimes the ball gets into the stands by some other means. I have studied the issue fairly extensively and written on it several times. My interest in the baseball area has led me to also examine the legal issues surrounding fans insured by wayward golf balls, soccer balls and mascot-tossed hotdogs.

A few weeks back a fan was serious injured (reportedly blinded in one eye) at the Ryder Cup, in Paris, when she was struck by a tee shot hit, on a par four, by U.S. golfer Brooks Koepka. It’s an awful situation. Koepka, who has no fault here, was nonetheless devastated. The fan has vowed to take legal action.

I have no idea how such a claim would be treated under French law. Golf.com decided to look into how it may be handled under U.S. law. I was really flattered when they reached out to me for my thoughts on the subject.

http://www.coverageopinions.info/RyderCupFan.pdf

With the caveat that tort law is extremely state specific, and facts matter a lot, my take on the Ryder Cup situation, based on the limited case law on the subject, is this. When it comes to fans injured by objects the leave the field of play, courts often turn to baseball cases for guidance. This is where the vast majority of the law – the cases are legion -- has been made.

The majority of courts that have confronted the question have adopted the so-called “Baseball Rule,” which limits the duty owed by baseball stadium operators to spectators injured by foul balls. The Baseball Rule generally provides that a baseball stadium operator is not liable for a foul ball injury as long as it screens the most dangerous part of the stadium and provides screened seats to as many spectators as may reasonably be expected to request them.

I believe that a court, analyzing liability for the injury at the Ryder Cup, would analogize it to the Baseball Rule. True, there was no screening in place where the fan -- standing in a dangerous location for a wayward tee shot on a par four -- was struck by the ball. However, unlike baseball, fans at golf tournaments stand on the course. This is unusual, but inherent to watching a golf tournament. There are not many other sports where the fans stand, in-bounds, on the field of play.

Given this, my take is that a court would absolve a golf tournament operator from liability so long as there are enough places on the course to watch the action (I know, not everyone would use that word when describing golf) where the risk of injury is minimal. In other words, the court would treat the availability of places on the course, to safely watch the play, as the baseball equivalent of making available screened-in areas in a stadium.

For example, it is safe to take in a golf tournament from behind a tee. It is also much safer to watch golf while sitting in the grandstand or standing at a green. Balls hit into the green usually do so at a high trajectory. And unlike a tee shot, approach shots to a green travel with less velocity and it is easier for a fan to see an errant shot coming his or her way. By offering fans these opportunities for safe viewing, I believe that a court would free a tournament operator from liability, for injury to a spectator, who chooses to stand where a wayward par four tee shot can go.

Having said this, I believe that an exception could also exist. In Duffy v. Midlothian Country Club, a 1985 decision from an Illinois appellate court, the court held that a tournament operator was liable, for serious injury to a fan (also blinded), when she was struck by a tee shot. The injury took place while the spectator was at a concession stand set up between the first and eighteenth fairways. However, here, the court seemed to be heavily influenced by expert testimony that “concession stands were placed in areas in which balls had regularly landed in the past, and that the fairways were so close together that the spectators located between the fairways are within range of balls likely to be hit by golfers. [And] spectators would not be able to see the player hitting the ball as the shrubbery and hills interfered with visibility.”

The situation in Duffy v. Midlothian Country Club, where there was this kind of evidence, about the hazards of the specific location of the fan, seems like an exceptional scenario.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Note To Policyholder Attorneys: How Not To Seek Fees (Do Not Miss This -- Trust Me)

|

|

|

|

I love this case. You will too. If there were a Saturday Night Live skit, of a policyholder counsel filing a fee petition – think John Belushi as the lawyer -- Clemens v. N.Y. Cent. Mut. Fire Ins. Co., No. 17-3150 (3d Cir. Sept. 12, 2018) would be it.

A jury awarded Bernie Clemens $100,000 in punitive damages, under Pennsylvania’s bad faith statute, in connection with a UIM claim. The ins and outs of that claim are not important (and the court does not even address them).

Following the award, Clemens, as a prevailing party under the bad faith statute, submitted a petition for attorney’s fees in an amount just shy of $950,000. The District Court, in a 100 page opinion, reviewing every time entry, concluded that the request was “outrageously excessive” and awarded no fees whatsoever. Zip. Nada. The case went to the Third Circuit which affirmed the award of no fees. Zilch. Goose egg. The Third Circuit, in a case of first impression for it, followed other circuits which have held that a District Court has the discretion to deny a fee request -- in its entirety -- when the requested amount is “outrageously excessive.”

The rationale for this rule, as explained by the court, is as follows: “Underlying these decisions is the idea that if courts did not possess this kind of discretion, claimants would be encouraged to make unreasonable demands, knowing that the only unfavorable consequence of such conduct would be reduction of their fee to what they should have asked for in the first place. We find this rationale persuasive. When a party submits a fee petition, it is not the ‘opening bid in the quest for an award.’ Rather, it is the duty of the requesting party to make a good faith effort to exclude . . . hours that are excessive, redundant, or otherwise unnecessary, just as a lawyer in private practice ethically is obligated to exclude such hours from his fee submission.” (citations omitted).

So what was it that caused the District Court, and then the Third Circuit, to conclude that the fee request was “outrageously excessive?” Here’s where the fun begins. I’ll let the Third Circuit describe the billing entries that it frowned upon.

“As a starting point, counsel did not maintain contemporaneous time records for most of the litigation. Instead, by their own admission, counsel ‘recreate[d]’ all of the records provided as part of the fee petition, using an electronic case management system that did not keep track of the amount of time expended on particular tasks. Even worse, the responsibility of reconstructing the time records was left to a single attorney, who retrospectively estimated not only the length of time she herself had spent on each individual task, but also the amount of time others had spent on particular tasks, including colleagues who could not be consulted because they had left the firm by the time the fee petition was filed.”

That’s good. But the court was just gettin’ warmed up.

“[M]any of the time entries submitted were so vague that there is no way to discern whether the hours billed were reasonable. Counsel’s time records included, for instance, entries billing for attorney services described as ‘Other,’ ‘Communicate,’ or ‘Communicate-other.’ Similarly, the fee petition included a number of entries for ‘Attorney review,’ ‘Analysis/Strategy,’ or ‘Review/analyze’ with no additional explanation regarding the subject or necessity of the review. We are mindful of confidentiality obligations, but time entries still must be specific enough to allow the district court to determine if the hours claimed are unreasonable for the work performed.”

I can understand a court not accepting “Other” or “Communicate” as acceptable billing entries. But to take issue with the one-two punch of “Communicate-other” is really outrageous.

The court continued…

“In addition to the vague entries, some entries were, on their face, unnecessary or excessive. For example, over the course of one week, and at the same time counsel were billing for trial preparation, counsel billed a total of sixty-four hours for ‘Transcripts/clips.’ Whatever this means, we are confident that it was not necessary to spend sixty-four hours on it given the straightforward nature of the case. Of a similar vein are the frequent entries that requested attorney rates for ‘File maintenance,’ ‘File management,’ and ‘Document management,’ some of which were for as long as seven hours in a single day. Without more information, these tasks appear ‘purely clerical’ in nature and should not be billed at a lawyer’s rate—nor for many hours at a time.”

“Then there are the staggering 562 hours that counsel billed for ‘Trial prep’ or ‘Trial preparation’ with no further description of the nature of the work performed. We agree with the District Court that this is an ‘outrageous’ number under the circumstances. As the District Court put it, ‘[i]f counsel did nothing else for eight hours a day, every day, [562 hours] would mean that counsel spent approximately 70 days doing nothing but preparing for trial in this matter.’ Yet the trial consisted of only four days of substantive testimony, and involved a total of only five witnesses for both sides. The sole issue was whether NYCM had acted in bad faith in its handling of Clemens’s UIM claim. Counsel certainly have an obligation to be prepared, but we simply cannot fathom how they could have reasonably spent such an astronomical amount of time preparing for trial in this case, and we highly doubt they would have billed their own client for all of the hours claimed.”

We now arrive at my favorite part:

“All the more troubling is the fact that counsel’s (supposedly) hard work did not appear to pay off at trial. As the District Court explained, counsel had ‘to be repeatedly admonished for not being prepared because he was obviously unfamiliar with the Federal Rules of Evidence, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the rulings of th[e] court.’ Given counsel’s subpar performance and the vagueness and excessiveness of the time entries, the District Court did not abuse its discretion in disallowing all 562 hours.”

With facts like these the case is seemingly (you would hope) an outlier. However, despite the truth-is-stranger-than-fiction aspect to it, the decision does include some valuable discussion, and case citations, concerning the proper manner for a prevailing party to submit a fee petition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Must Read For Insurers That Use A&B Exclusions – Court Finds It Ambiguous (For A Reason You Might Not Think)

|

|

|

|

I have no statistical proof of this, but, anecdotally, I can say with confidence that insurers win a lot more cases involving the Assault and Battery exclusion than they lose. Insurers tend to use broad A&B exclusions that cover both the act of the assault and battery, as well as claims against the insured for negligent hiring, negligent training, negligent supervision, etc. In other words, the exclusions preclude coverage for assault and battery and failing to prevent the assault and battery.

Given this, I read with interest the Nevada federal court’s decision in Atain Specialty Ins. Co. v. Reno Cab Co., No. 15-406 (D. Nev. Sept. 14, 2018) as the court found against the insurer in its attempt to apply an A&B exclusion. It is a serious decision for insurers that handle claims that, by their nature, invoke the A&B exclusion.

The case involves the potential availability of coverage, under a general liability policy, for a dispute over a cab fare that resulted in a death. Claims for wrongful death, battery and negligent training and supervision were asserted against Reno Cab Company. The cab company’s insurer, Atain Specialty, asserted that no coverage was owed, for defense or indemnity, on the basis of an assault and battery exclusion, which provided as follows:

This insurance does not apply under COVERAGE A BODILY INJURY AND PROPERTY DAMAGE LIABILITY and COVERAGE B PERSONAL AND ADVERTISING INJURY LIABILITY arising from:

1. Assault and Battery committed by any Insured, any employee of any Insured or any other person;

2. The failure to suppress or prevent Assault and Battery by any person in 1. above;

3. Any Assault or Battery resulting from or allegedly related to the negligent hiring, supervision, or training of any employee of the Insured; or

4. Assault or Battery, whether or not caused by or arising out of negligent, reckless or wanton conduct of the Insured, the Insured's employees, patrons or other persons lawfully or otherwise on, at or near the premises owned or occupied by the Insureds, or by any other person.

Reno Cab argued that the A&B exclusion was ambiguous, as to whether it applied to self-defense, since the Expected or Intended Exclusion contained a self-defense exception: “‘Bodily injury’ or ‘property damage’ expected or intended from the standpoint of the insured. This exclusion does not apply to ‘bodily injury’ resulting from the use of reasonable force to protect persons or property.”

The court rejected the insurer’s argument, among others, that exclusions operate independently of each other and should be read separately. The court sided with Reno Cab: “The Court agrees with Reno Cab that the Assault and Battery Exclusion conflicts with the Expected or Intended Injury Exclusion and creates ambiguity. An assault or battery is an intentional act, which brings it within the scope of both the Assault and Battery Exclusion and the Expected or Intended Injury Exclusion, yet only the Expected or Intended Injury Exclusion includes a carve-out for self-defense. Accepting Atain’s contention that self-defense necessarily constitutes an assault and battery, this inconsistency leads to two competing interpretations of the Policy: on the one hand, the Policy covers self-defense characterized as an intentional act, and on the other hand, the Policy excludes coverage for self-defense characterized as an assault and battery. An insurance policy is considered ambiguous if it creates multiple reasonable expectations of coverage as drafted. In light of this ambiguity, the Court must construe the Assault and Battery Exclusion in favor of coverage.”

This is a serious decision for insurers that handle claims that, by their nature, invoke the A&B exclusion. The reason being that the self-defense exception, contained in the Expected or Intended exclusion, is likely contained in their policies too. It is a standard exclusion in the ISO commercial general liability policy. Thus, the rationale for Reno Cab -- that the combination of an Expected or Intended Exclusion with a self-defense exception, and an A&B exclusion with no self-defense exception, is ambiguous -- is open to wide-spread applicability. Insurers that handle claims, that invoke the A&B exclusion, would be well-served to consider a possible response in their policies.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

3rd Circuit, Quoting Hogan’s Heroes, Says Pennsylvania Is Seriously “Four Corners”

How Exciting: Appeals Court Cites Insurance Key Issues In Reaching Its Decision

|

|

|

|

[It was exciting to see that the Third Circuit cited Insurance Key Issues in a recent duty to defend case. Key Issues has not been getting attention from the courts. This was only the second citing. But that doesn’t bother me. The book is not scholarly. And I wear that fact with a badge of honor. Key Issues is designed to be practical. It provides answers – not legal theory. If you – or courts -- want scholarly, there are plenty of excellent treatises out there.]

***

I have always considered Pennsylvania to be a strict “four corners” state for purposes of determining an insurer’s duty to defend. [An exception being that a court may be willing to ignore a “negligence” allegation if the complaint belies that a defendant-insured’s actions could have been negligent.]

In Lupu v. Loan City, LLC, No. 17-1944 (3d Cir. Sept. 10, 2018) (published), the strictness of Pennsylvania’s “four corners” test was, well, put to the test. The facts at issue are crazy complex. It would take forever to summarize them – and for no reason. Thus, I limit the discussion to the court’s legal analysis, which addressed a title insurance policy.

The Third Circuit acknowledged that Pennsylvania has long employed the “four corners” test for purposes of determining an insurer’s duty to defend. The court also had no hesitation pointing out shortcomings of the four corners rule: “[T]he inflexible application the ‘four corners’ rule allows an insurer to plead Sergeant Schultz’s ‘know nothing’ defense, and thereby successfully ignor[e] true but unpleaded facts within its knowledge that require it, under the insurance policy, to conduct the putative insureds defense.” Further, the court conceded that “harsh consequences [] can be wrought by the ‘four corners’ rule, and no doubt a wooden application leaves would-be insureds in the lurch if a covered claim is not identifiable in the complaint. But Pennsylvania courts tolerate this measure of concern in exchange for a clear rule’s benefit.” The court acknowledged that, under the four corners rule, the party seeking insurance is left at the mercy of the manner in which the underlying plaintiff pleads its case.

Against this backdrop of the four corners shortcomings, the Lupu court pointed out that a majority of courts have departed from the rule -- and require the insurer to consider extrinsic evidence when determining if an insurer is obligated to defend. In support, the court pointed to the dissenting opinion, in the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Water Well Sols. Serv. Grp. v. Consol. Ins. Co., which noted that 31 states allow for the consideration of extrinsic evidence.

The question before the Lupu court was this. In its 2006 decision, in Kvaerner Metals v. Commercial Union, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court declined to adopt an exception to the four corners rule. Does the strict four corners rule apply when the outside facts are introduced by the plaintiff and not the insured. [Again, how this issue arose is quite complex.] The court concluded – despite one “misfit” case from 1992 – that four corners was king, stating: “Pennsylvania courts have identified no exception to the time-honored rule . . . in Kvaerner. Legal commentators concur. For instance, one source counts Pennsylvania among the states in which ‘the answer is simple—No. Courts are not permitted to consider extrinsic evidence[.]’ Randy Maniloff & Jeffrey Stempel, General Liability Insurance Coverage: Key Issues In Every State 69-74, 89 (1st ed. 2011).”

It was neat to see that the Lupu court cited to Insurance Key Issues in reaching this decision. Although it would have been even better if the court had sprung for a copy of the 4th edition. In any event, I have always considered Pennsylvania to be a strict “four corners” state. And I still do. Having said that, I’d like to see a Pennsylvania appellate court address whether an insurer can look to extrinsic facts, to deny a duty to defend, when such facts are “coverage only,” i.e., not at issue in the underlying action.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Vol. 7 - Issue 8

November 7, 2018

Wow!: Court Holds That Trade Secrets, Being Tangible Property, Are “Property Damage”

|

|

|

|

While a standard commercial general liability policy provides coverage, under “personal and advertising injury,” for certain types of intellectual property claims, under certain circumstances, theft of trade secrets is not one of them. But in Richerme v. Trumball Insurance Co., 18-1286 (N.D. Ill. Oct. 23, 2018) an Illinois federal court would have found coverage, for theft of trade secrets, under a homeowner’s policy (if not for an unrelated exclusion). And the court went the “property damage” route.

Theft of trade secrets claims, under homeowner’s policies, is probably not keeping insurers awake at night. But since the rationale for this decision would apply to CGL policies – and such types of claims are sometimes made -- it is worth a look see here.

Engineered Abrasives sued Edward and Karen Richerme for theft of trade secrets. The facts – quite technical – were described by the court as follows: “Engineered Abrasives, Inc., manufactured automated blast-finishing, shot-peening equipment, and replacement parts for those machines. On April 27, 2017, it served the Richermes and their son (Edward C. Richerme) with a complaint alleging trade-secret violations, conversion, tortious interference with prospective economic advantage, and civil conspiracy. In the complaint, Engineered Abrasives alleged that their shot-peening valve sleeves, springs, and seats contained a trade secret, and that over the years it had accumulated numerous trade secrets and confidential information including tooling designs, drawings, fixtures, special designs, spare parts, pricing information, manufacturing, distribution processes, patented machines and patented processes, all of which Edward Richerme and his son had access to while they worked there. When Engineered Abrasives terminated Edward C. Richerme, the complaint asserted, he began using its trade secrets to sell replacement parts and with his parents help published the trade secrets to Engineered Abrasives’s customers and competitors.”

The Richerme’s sought coverage for the suit from their homeowner’s insurer, Trumball Insurance Company. Trumball denied a defense and the Richerme’s filed the coverage action.

The court addressed whether the theft of trade secrets qualified as “bodily injury” or “property damage” to trigger coverage under the homeowner’s policy. Clearly “bodily injury” was not at issue so the court turned to whether there was “property damage.” “Property damage” was defined to include “physical injury to, destruction of, or loss of use of tangible property.”

Trumball argued, as you would expect, that trade secrets are intellectual property, and, therefore, not “property damage.” But the court saw it differently, noting that, under the Illinois Trade Secrets Act, a trade secret can be tangible property. The Act defined “trade secret” as “information, including but not limited to . . . [a] device, method, technique, drawing, process, financial data, or list of actual or potential customers or suppliers that is sufficiently secret to derive economic value and subject to reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy.

Based on this definition, the court concluded that the complaint alleged “property damage,” as Engineered Abrasives alleged that the Richermes misappropriated its trade secrets, including its designs and drawings, which are tangible items. Even if that’s the case, the court did not address the physical injury to, destruction of, or loss of use requirements.